Related Research Articles

An endosymbiont or endobiont is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship. (The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον endon "within", σύν syn "together" and βίωσις biosis "living".) Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria, which live in the root nodules of legumes, single-cell algae inside reef-building corals and bacterial endosymbionts that provide essential nutrients to insects.

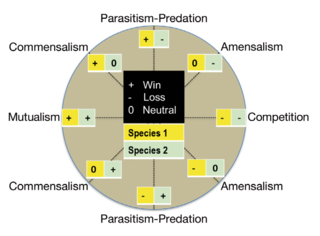

Symbiosis is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two biological organisms of different species, termed symbionts, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasitic. In 1879, Heinrich Anton de Bary defined it as "the living together of unlike organisms". The term is sometimes used in the more restricted sense of a mutually beneficial interaction in which both symbionts contribute to each other's support.

Riftia pachyptila, commonly known as the giant tube worm and less commonly known as the giant beardworm, is a marine invertebrate in the phylum Annelida related to tube worms commonly found in the intertidal and pelagic zones. R. pachyptila lives on the floor of the Pacific Ocean near hydrothermal vents. The vents provide a natural ambient temperature in their environment ranging from 2 to 30 °C, and this organism can tolerate extremely high hydrogen sulfide levels. These worms can reach a length of 3 m, and their tubular bodies have a diameter of 4 cm (1.6 in).

In prokaryote nomenclature, Candidatus is used to name prokaryotic phyla that are well characterized but yet-uncultured. Contemporary sequencing approaches, such as 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing or metagenomics, provide much information about the analyzed organisms and thus allow to identify and characterize individual species. However, the majority of prokaryotic species remain uncultivable and hence inaccessible for further characterization in in vitro study. The recent discoveries of a multitude of candidate taxa has led to candidate phyla radiation expanding the tree of life through the new insights in bacterial diversity.

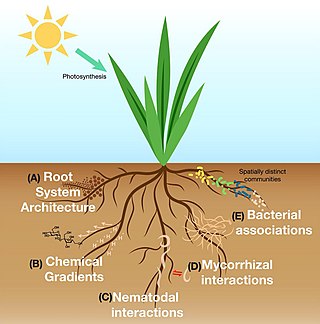

The rhizosphere is the narrow region of soil or substrate that is directly influenced by root secretions and associated soil microorganisms known as the root microbiome. Soil pores in the rhizosphere can contain many bacteria and other microorganisms that feed on sloughed-off plant cells, termed rhizodeposition, and the proteins and sugars released by roots, termed root exudates. This symbiosis leads to more complex interactions, influencing plant growth and competition for resources. Much of the nutrient cycling and disease suppression by antibiotics required by plants, occurs immediately adjacent to roots due to root exudates and metabolic products of symbiotic and pathogenic communities of microorganisms. The rhizosphere also provides space to produce allelochemicals to control neighbours and relatives.

Symbiotic bacteria are bacteria living in symbiosis with another organism or each other. For example, rhizobia living in root nodules of legumes provide nitrogen fixing activity for these plants.

Horizontal transmission is the transmission of organisms between biotic and/or abiotic members of an ecosystem that are not in a parent-progeny relationship. This concept has been generalized to include transmissions of infectious agents, symbionts, and cultural traits between humans.

Gammaproteobacteria is a class of bacteria in the phylum Pseudomonadota. It contains about 250 genera, which makes it the most genus-rich taxon of the Prokaryotes. Several medically, ecologically, and scientifically important groups of bacteria belong to this class. It is composed by all Gram-negative microbes and is the most phylogenetically and physiologically diverse class of Proteobacteria.

Cyanobionts are cyanobacteria that live in symbiosis with a wide range of organisms such as terrestrial or aquatic plants; as well as, algal and fungal species. They can reside within extracellular or intracellular structures of the host. In order for a cyanobacterium to successfully form a symbiotic relationship, it must be able to exchange signals with the host, overcome defense mounted by the host, be capable of hormogonia formation, chemotaxis, heterocyst formation, as well as possess adequate resilience to reside in host tissue which may present extreme conditions, such as low oxygen levels, and/or acidic mucilage. The most well-known plant-associated cyanobionts belong to the genus Nostoc. With the ability to differentiate into several cell types that have various functions, members of the genus Nostoc have the morphological plasticity, flexibility and adaptability to adjust to a wide range of environmental conditions, contributing to its high capacity to form symbiotic relationships with other organisms. Several cyanobionts involved with fungi and marine organisms also belong to the genera Richelia, Calothrix, Synechocystis, Aphanocapsa and Anabaena, as well as the species Oscillatoria spongeliae. Although there are many documented symbioses between cyanobacteria and marine organisms, little is known about the nature of many of these symbioses. The possibility of discovering more novel symbiotic relationships is apparent from preliminary microscopic observations.

The hologenome theory of evolution recasts the individual animal or plant as a community or a "holobiont" – the host plus all of its symbiotic microbes. Consequently, the collective genomes of the holobiont form a "hologenome". Holobionts and hologenomes are structural entities that replace misnomers in the context of host-microbiota symbioses such as superorganism, organ, and metagenome. Variation in the hologenome may encode phenotypic plasticity of the holobiont and can be subject to evolutionary changes caused by selection and drift, if portions of the hologenome are transmitted between generations with reasonable fidelity. One of the important outcomes of recasting the individual as a holobiont subject to evolutionary forces is that genetic variation in the hologenome can be brought about by changes in the host genome and also by changes in the microbiome, including new acquisitions of microbes, horizontal gene transfers, and changes in microbial abundance within hosts. Although there is a rich literature on binary host–microbe symbioses, the hologenome concept distinguishes itself by including the vast symbiotic complexity inherent in many multicellular hosts. For recent literature on holobionts and hologenomes published in an open access platform, see the following reference.

The root microbiome is the dynamic community of microorganisms associated with plant roots. Because they are rich in a variety of carbon compounds, plant roots provide unique environments for a diverse assemblage of soil microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi and archaea. The microbial communities inside the root and in the rhizosphere are distinct from each other, and from the microbial communities of bulk soil, although there is some overlap in species composition.

A microbiome is the community of microorganisms that can usually be found living together in any given habitat. It was defined more precisely in 1988 by Whipps et al. as "a characteristic microbial community occupying a reasonably well-defined habitat which has distinct physio-chemical properties. The term thus not only refers to the microorganisms involved but also encompasses their theatre of activity". In 2020, an international panel of experts published the outcome of their discussions on the definition of the microbiome. They proposed a definition of the microbiome based on a revival of the "compact, clear, and comprehensive description of the term" as originally provided by Whipps et al., but supplemented with two explanatory paragraphs. The first explanatory paragraph pronounces the dynamic character of the microbiome, and the second explanatory paragraph clearly separates the term microbiota from the term microbiome.

Microbial symbiosis in marine animals was not discovered until 1981. In the time following, symbiotic relationships between marine invertebrates and chemoautotrophic bacteria have been found in a variety of ecosystems, ranging from shallow coastal waters to deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Symbiosis is a way for marine organisms to find creative ways to survive in a very dynamic environment. They are different in relation to how dependent the organisms are on each other or how they are associated. It is also considered a selective force behind evolution in some scientific aspects. The symbiotic relationships of organisms has the ability to change behavior, morphology and metabolic pathways. With increased recognition and research, new terminology also arises, such as holobiont, which the relationship between a host and its symbionts as one grouping. Many scientists will look at the hologenome, which is the combined genetic information of the host and its symbionts. These terms are more commonly used to describe microbial symbionts.

The mycobiome, mycobiota, or fungal microbiome, is the fungal community in and on an organism.

A holobiont is an assemblage of a host and the many other species living in or around it, which together form a discrete ecological unit through symbiosis, though there is controversy over this discreteness. The components of a holobiont are individual species or bionts, while the combined genome of all bionts is the hologenome. The holobiont concept was initially introduced by the German theoretical biologist Adolf Meyer-Abich in 1943, and then apparently independently by Dr. Lynn Margulis in her 1991 book Symbiosis as a Source of Evolutionary Innovation. The concept has evolved since the original formulations. Holobionts include the host, virome, microbiome, and any other organisms which contribute in some way to the functioning of the whole. Well-studied holobionts include reef-building corals and humans.

Hologenomics is the omics study of hologenomes. A hologenome is the whole set of genomes of a holobiont, an organism together with all co-habitating microbes, other life forms, and viruses. While the term hologenome originated from the hologenome theory of evolution, which postulates that natural selection occurs on the holobiont level, hologenomics uses an integrative framework to investigate interactions between the host and its associated species. Examples include gut microbe or viral genomes linked to human or animal genomes for host-microbe interaction research. Hologenomics approaches have also been used to explain genetic diversity in the microbial communities of marine sponges.

All animals on Earth form associations with microorganisms, including protists, bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses. In the ocean, animal–microbial relationships were historically explored in single host–symbiont systems. However, new explorations into the diversity of marine microorganisms associating with diverse marine animal hosts is moving the field into studies that address interactions between the animal host and a more multi-member microbiome. The potential for microbiomes to influence the health, physiology, behavior, and ecology of marine animals could alter current understandings of how marine animals adapt to change, and especially the growing climate-related and anthropogenic-induced changes already impacting the ocean environment.

Richelia is a genus of nitrogen-fixing, filamentous, heterocystous and cyanobacteria. It contains the single species Richelia intracellularis. They exist as both free-living organisms as well as symbionts within potentially up to 13 diatoms distributed throughout the global ocean. As a symbiont, Richelia can associate epiphytically and as endosymbionts within the periplasmic space between the cell membrane and cell wall of diatoms.

The holobiont concept is a renewed paradigm in biology that can help to describe and understand complex systems, like the host-microbe interactions that play crucial roles in marine ecosystems. However, there is still little understanding of the mechanisms that govern these relationships, the evolutionary processes that shape them and their ecological consequences. The holobiont concept posits that a host and its associated microbiota with which it interacts, form a holobiont, and have to be studied together as a coherent biological and functional unit to understand its biology, ecology, and evolution.

Amoebozoa of the free living genus Acanthamoeba and the social amoeba genus Dictyostelium are single celled eukaryotic organisms that feed on bacteria, fungi, and algae through phagocytosis, with digestion occurring in phagolysosomes. Amoebozoa are present in most terrestrial ecosystems including soil and freshwater. Amoebozoa contain a vast array of symbionts that range from transient to permanent infections, confer a range of effects from mutualistic to pathogenic, and can act as environmental reservoirs for animal pathogenic bacteria. As single celled phagocytic organisms, amoebas simulate the function and environment of immune cells like macrophages, and as such their interactions with bacteria and other microbes are of great importance in understanding functions of the human immune system, as well as understanding how microbiomes can originate in eukaryotic organisms.

References

- 1 2 Douglas, Angela E. (2010-04-08). The Symbiotic Habit. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3543-0.

- ↑ Moran, Nancy A. (2006-10-24). "Symbiosis". Current Biology. 16 (20): R866–R871. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.019 . ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 17055966.

- ↑ Wang, Dong; Yang, Shengming; Tang, Fang; Zhu, Hongyan (2012). "Symbiosis specificity in the legume – rhizobial mutualism". Cellular Microbiology. 14 (3): 334–342. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01736.x. ISSN 1462-5822. PMID 22168434. S2CID 34904633.

- ↑ Mandel, Mark J. (2010-11-01). "Models and approaches to dissect host–symbiont specificity". Trends in Microbiology. 18 (11): 504–511. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2010.07.005. ISSN 0966-842X. PMID 20729086.

- ↑ Itoh, Hideomi; Jang, Seonghan; Takeshita, Kazutaka; Ohbayashi, Tsubasa; Ohnishi, Naomi; Meng, Xian-Ying; Mitani, Yasuo; Kikuchi, Yoshitomo (2019-11-05). "Host–symbiont specificity determined by microbe–microbe competition in an insect gut". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (45): 22673–22682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1912397116 . ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6842582 . PMID 31636183.