Ferromagnetism is a property of certain materials which results in a large observed magnetic permeability, and in many cases a large magnetic coercivity allowing the material to form a permanent magnet. Ferromagnetic materials are the familiar metals noticeably attracted to a magnet, a consequence of their large magnetic permeability. Magnetic permeability describes the induced magnetization of a material due to the presence of an external magnetic field, and it is this temporarily induced magnetization inside a steel plate, for instance, which accounts for its attraction to the permanent magnet. Whether or not that steel plate acquires a permanent magnetization itself, depends not only on the strength of the applied field, but on the so-called coercivity of that material, which varies greatly among ferromagnetic materials.

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that are mediated by a magnetic field, which refers to the capacity to induce attractive and repulsive phenomena in other entities. Electric currents and the magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, which acts on other currents and magnetic moments. Magnetism is one aspect of the combined phenomena of electromagnetism. The most familiar effects occur in ferromagnetic materials, which are strongly attracted by magnetic fields and can be magnetized to become permanent magnets, producing magnetic fields themselves. Demagnetizing a magnet is also possible. Only a few substances are ferromagnetic; the most common ones are iron, cobalt and nickel and their alloys. The rare-earth metals neodymium and samarium are less common examples. The prefix ferro- refers to iron, because permanent magnetism was first observed in lodestone, a form of natural iron ore called magnetite, Fe3O4.

Paramagnetism is a form of magnetism whereby some materials are weakly attracted by an externally applied magnetic field, and form internal, induced magnetic fields in the direction of the applied magnetic field. In contrast with this behavior, diamagnetic materials are repelled by magnetic fields and form induced magnetic fields in the direction opposite to that of the applied magnetic field. Paramagnetic materials include most chemical elements and some compounds; they have a relative magnetic permeability slightly greater than 1 and hence are attracted to magnetic fields. The magnetic moment induced by the applied field is linear in the field strength and rather weak. It typically requires a sensitive analytical balance to detect the effect and modern measurements on paramagnetic materials are often conducted with a SQUID magnetometer.

In physics, a state of matter is one of the distinct forms in which matter can exist. Four states of matter are observable in everyday life: solid, liquid, gas, and plasma. Many intermediate states are known to exist, such as liquid crystal, and some states only exist under extreme conditions, such as Bose–Einstein condensates, neutron-degenerate matter, and quark–gluon plasma. For a complete list of all exotic states of matter, see the list of states of matter.

Orbital inclination measures the tilt of an object's orbit around a celestial body. It is expressed as the angle between a reference plane and the orbital plane or axis of direction of the orbiting object.

In materials that exhibit antiferromagnetism, the magnetic moments of atoms or molecules, usually related to the spins of electrons, align in a regular pattern with neighboring spins pointing in opposite directions. This is, like ferromagnetism and ferrimagnetism, a manifestation of ordered magnetism. The phenomenon of antiferromagnetism was first introduced by Lev Landau in 1933.

In condensed matter physics, a spin glass is a magnetic state characterized by randomness, besides cooperative behavior in freezing of spins at a temperature called 'freezing temperature' Tf. Magnetic spins are, roughly speaking, the orientation of the north and south magnetic poles in three-dimensional space. In ferromagnetic solids, component atoms' magnetic spins all align in the same direction. Spin glass when contrasted with a ferromagnet is defined as "disordered" magnetic state in which spins are aligned randomly or not with a regular pattern and the couplings too are random.

The Fermi level of a solid-state body is the thermodynamic work required to add one electron to the body. It is a thermodynamic quantity usually denoted by µ or EF for brevity. The Fermi level does not include the work required to remove the electron from wherever it came from. A precise understanding of the Fermi level—how it relates to electronic band structure in determining electronic properties, how it relates to the voltage and flow of charge in an electronic circuit—is essential to an understanding of solid-state physics.

In physics and materials science, the Curie temperature (TC), or Curie point, is the temperature above which certain materials lose their permanent magnetic properties, which can be replaced by induced magnetism. The Curie temperature is named after Pierre Curie, who showed that magnetism was lost at a critical temperature.

In atmospheric science, geostrophic flow is the theoretical wind that would result from an exact balance between the Coriolis force and the pressure gradient force. This condition is called geostrophic equilibrium or geostrophic balance. The geostrophic wind is directed parallel to isobars. This balance seldom holds exactly in nature. The true wind almost always differs from the geostrophic wind due to other forces such as friction from the ground. Thus, the actual wind would equal the geostrophic wind only if there were no friction and the isobars were perfectly straight. Despite this, much of the atmosphere outside the tropics is close to geostrophic flow much of the time and it is a valuable first approximation. Geostrophic flow in air or water is a zero-frequency inertial wave.

In electromagnetism, permeability is the measure of magnetization that a material obtains in response to an applied magnetic field. Permeability is typically represented by the (italicized) Greek letter μ. The term was coined by William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin in 1872, and used alongside permittivity by Oliver Heaviside in 1885. The reciprocal of permeability is magnetic reluctivity.

In physical organic chemistry, a kinetic isotope effect (KIE) is the change in the reaction rate of a chemical reaction when one of the atoms in the reactants is replaced by one of its isotopes. Formally, it is the ratio of rate constants for the reactions involving the light (kL) and the heavy (kH) isotopically substituted reactants (isotopologues):

Dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) results from transferring spin polarization from electrons to nuclei, thereby aligning the nuclear spins to the extent that electron spins are aligned. Note that the alignment of electron spins at a given magnetic field and temperature is described by the Boltzmann distribution under the thermal equilibrium. It is also possible that those electrons are aligned to a higher degree of order by other preparations of electron spin order such as: chemical reactions, optical pumping and spin injection. DNP is considered one of several techniques for hyperpolarization. DNP can also be induced using unpaired electrons produced by radiation damage in solids.

Rock magnetism is the study of the magnetic properties of rocks, sediments and soils. The field arose out of the need in paleomagnetism to understand how rocks record the Earth's magnetic field. This remanence is carried by minerals, particularly certain strongly magnetic minerals like magnetite. An understanding of remanence helps paleomagnetists to develop methods for measuring the ancient magnetic field and correct for effects like sediment compaction and metamorphism. Rock magnetic methods are used to get a more detailed picture of the source of the distinctive striped pattern in marine magnetic anomalies that provides important information on plate tectonics. They are also used to interpret terrestrial magnetic anomalies in magnetic surveys as well as the strong crustal magnetism on Mars.

A control moment gyroscope (CMG) is an attitude control device generally used in spacecraft attitude control systems. A CMG consists of a spinning rotor and one or more motorized gimbals that tilt the rotor’s angular momentum. As the rotor tilts, the changing angular momentum causes a gyroscopic torque that rotates the spacecraft.

Exchange bias or exchange anisotropy occurs in bilayers of magnetic materials where the hard magnetization behavior of an antiferromagnetic thin film causes a shift in the soft magnetization curve of a ferromagnetic film. The exchange bias phenomenon is of tremendous utility in magnetic recording, where it is used to pin the state of the readback heads of hard disk drives at exactly their point of maximum sensitivity; hence the term "bias."

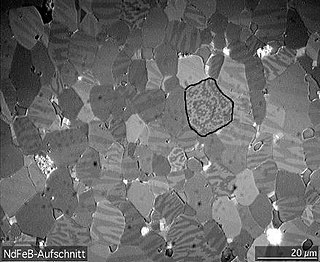

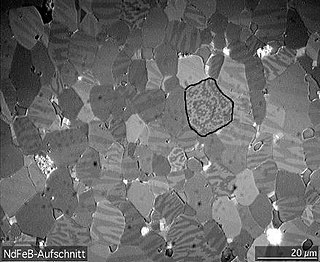

A magnetic domain is a region within a magnetic material in which the magnetization is in a uniform direction. This means that the individual magnetic moments of the atoms are aligned with one another and they point in the same direction. When cooled below a temperature called the Curie temperature, the magnetization of a piece of ferromagnetic material spontaneously divides into many small regions called magnetic domains. The magnetization within each domain points in a uniform direction, but the magnetization of different domains may point in different directions. Magnetic domain structure is responsible for the magnetic behavior of ferromagnetic materials like iron, nickel, cobalt and their alloys, and ferrimagnetic materials like ferrite. This includes the formation of permanent magnets and the attraction of ferromagnetic materials to a magnetic field. The regions separating magnetic domains are called domain walls, where the magnetization rotates coherently from the direction in one domain to that in the next domain. The study of magnetic domains is called micromagnetics.

Magnets exert forces and torques on each other due to the rules of electromagnetism. The forces of attraction field of magnets are due to microscopic currents of electrically charged electrons orbiting nuclei and the intrinsic magnetism of fundamental particles that make up the material. Both of these are modeled quite well as tiny loops of current called magnetic dipoles that produce their own magnetic field and are affected by external magnetic fields. The most elementary force between magnets is the magnetic dipole–dipole interaction. If all of the magnetic dipoles that make up two magnets are known then the net force on both magnets can be determined by summing up all these interactions between the dipoles of the first magnet and that of the second.

Magnetochemistry is concerned with the magnetic properties of chemical compounds. Magnetic properties arise from the spin and orbital angular momentum of the electrons contained in a compound. Compounds are diamagnetic when they contain no unpaired electrons. Molecular compounds that contain one or more unpaired electrons are paramagnetic. The magnitude of the paramagnetism is expressed as an effective magnetic moment, μeff. For first-row transition metals the magnitude of μeff is, to a first approximation, a simple function of the number of unpaired electrons, the spin-only formula. In general, spin-orbit coupling causes μeff to deviate from the spin-only formula. For the heavier transition metals, lanthanides and actinides, spin-orbit coupling cannot be ignored. Exchange interaction can occur in clusters and infinite lattices, resulting in ferromagnetism, antiferromagnetism or ferrimagnetism depending on the relative orientations of the individual spins.

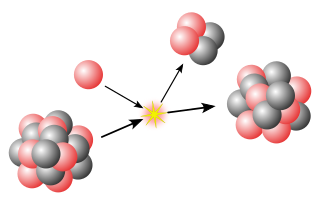

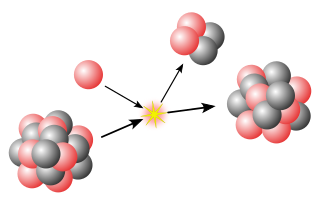

In nuclear physics, properties of a nucleus depend on evenness or oddness of its atomic number Z, neutron number N and, consequently, of their sum, the mass number A. Most importantly, oddness of both Z and N tends to lower the nuclear binding energy, making odd nuclei generally less stable. This effect is not only experimentally observed, but is included in the semi-empirical mass formula and explained by some other nuclear models, such as the nuclear shell model. This difference of nuclear binding energy between neighbouring nuclei, especially of odd-A isobars, has important consequences for beta decay.