The Kayenta Formation is a geological formation in the Glen Canyon Group that is spread across the Colorado Plateau province of the United States, including northern Arizona, northwest Colorado, Nevada, and Utah. Traditionally has been suggested as Sinemurian-Pliensbachian, but more recent dating of detrital zircons has yielded a depositional age of 183.7 ± 2.7 Ma, thus a Pliensbachian-Toarcian age is more likely. A previous depth work recovered a solid "Carixian" age from measurements done in the Tenney Canyon. More recent works have provided varied datations for the layers, with samples from Colorado and Arizona suggesting 197.0±1.5-195.2±5.5 Ma, while the topmost section is likely Toarcian or close in age, maybe even recovering terrestrial deposits coeval with the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event. This last age asignation also correlated the Toarcian Vulcanism on the west Cordilleran Magmatic Arc, as the number of grains from this event correlate with the silt content in the sandstones of the upper layers.

A fossil track or ichnite is a fossilized footprint. This is a type of trace fossil. A fossil trackway is a sequence of fossil tracks left by a single organism. Over the years, many ichnites have been found, around the world, giving important clues about the behaviour of the animals that made them. For instance, multiple ichnites of a single species, close together, suggest 'herd' or 'pack' behaviour of that species.

The Black Peaks Formation is a geological formation in Texas whose strata date back to the Late Cretaceous. Dinosaur remains and the pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus northropi have been among the fossils reported from the formation. The boundary with the underlying Javelina Formation has been estimated at 66.5 million years old. The formation preserves the rays Rhombodus and Dasyatis, as well as many gar scales.

Dinosaur Ridge is a segment of the Dakota Hogback in the Morrison Fossil Area National Natural Landmark located in Jefferson County, Colorado, near the town of Morrison and just west of Denver.

The Moenave Formation is a Mesozoic geologic formation, in the Glen Canyon Group. It is found in Utah and Arizona.

Paleontology in Maryland refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Maryland. The invertebrate fossils of Maryland are similar to those of neighboring Delaware. For most of the early Paleozoic era, Maryland was covered by a shallow sea, although it was above sea level for portions of the Ordovician and Devonian. The ancient marine life of Maryland included brachiopods and bryozoans while horsetails and scale trees grew on land. By the end of the era, the sea had left the state completely. In the early Mesozoic, Pangaea was splitting up. The same geologic forces that divided the supercontinent formed massive lakes. Dinosaur footprints were preserved along their shores. During the Cretaceous, the state was home to dinosaurs. During the early part of the Cenozoic era, the state was alternatingly submerged by sea water or exposed. During the Ice Age, mastodons lived in the state.

Paleontology in Pennsylvania refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. The geologic column of Pennsylvania spans from the Precambrian to Quaternary. During the early part of the Paleozoic, Pennsylvania was submerged by a warm, shallow sea. This sea would come to be inhabited by creatures like brachiopods, bryozoans, crinoids, graptolites, and trilobites. The armored fish Palaeaspis appeared during the Silurian. By the Devonian the state was home to other kinds of fishes. On land, some of the world's oldest tetrapods left behind footprints that would later fossilize. Some of Pennsylvania's most important fossil finds were made in the state's Devonian rocks. Carboniferous Pennsylvania was a swampy environment covered by a wide variety of plants. The latter half of the period was called the Pennsylvanian in honor of the state's rich contemporary rock record. By the end of the Paleozoic the state was no longer so swampy. During the Mesozoic the state was home to dinosaurs and other kinds of reptiles, who left behind fossil footprints. Little is known about the early to mid Cenozoic of Pennsylvania, but during the Ice Age it seemed to have a tundra-like environment. Local Delaware people used to smoke mixtures of fossil bones and tobacco for good luck and to have wishes granted. By the late 1800s Pennsylvania was the site of formal scientific investigation of fossils. Around this time Hadrosaurus foulkii of neighboring New Jersey became the first mounted dinosaur skeleton exhibit at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. The Devonian trilobite Phacops rana is the Pennsylvania state fossil.

Paleontology in New Jersey refers to paleontological research in the U.S. state of New Jersey. The state is especially rich in marine deposits.

Paleontology in Connecticut refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Connecticut. Apart from its famous dinosaur tracks, the fossil record in Connecticut is relatively sparse. The oldest known fossils in Connecticut date back to the Triassic period. At the time, Pangaea was beginning to divide and local rift valleys became massive lakes. A wide variety of vegetation, invertebrates and reptiles are known from Triassic Connecticut. During the Early Jurassic local dinosaurs left behind an abundance of footprints that would later fossilize.

Paleontology in Arkansas refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Arkansas. The fossil record of Arkansas spans from the Ordovician to the Eocene. Nearly all of the state's fossils have come from ancient invertebrate life. During the early Paleozoic, much of Arkansas was covered by seawater. This sea would come to be home to creatures including Archimedes, brachiopods, and conodonts. This sea would begin its withdrawal during the Carboniferous, and by the Permian the entire state was dry land. Terrestrial conditions continued into the Triassic, but during the Jurassic, another sea encroached into the state's southern half. During the Cretaceous the state was still covered by seawater and home to marine invertebrates such as Belemnitella. On land the state was home to long necked sauropod dinosaurs, who left behind footprints and ostrich dinosaurs such as Arkansaurus.

Paleontology in Kansas refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Kansas. Kansas has been the source of some of the most spectacular fossil discoveries in US history. The fossil record of Kansas spans from the Cambrian to the Pleistocene. From the Cambrian to the Devonian, Kansas was covered by a shallow sea. During the ensuing Carboniferous the local sea level began to rise and fall. When sea levels were low the state was home to richly vegetated deltaic swamps where early amphibians and reptiles lived. Seas expanded across most of the state again during the Permian, but on land the state was home to thousands of different insect species. The popular pterosaur Pteranodon is best known from this state. During the early part of the Cenozoic era Kansas became a savannah environment. Later, during the Ice Age, glaciers briefly entered the state, which was home to camels, mammoths, mastodons, and saber-teeth. Local fossils may have inspired Native Americans to regard some local hills as the homes of sacred spirit animals. Major scientific discoveries in Kansas included the pterosaur Pteranodon and a fossil of the fish Xiphactinus that died in the act of swallowing another fish.

Paleontology in Wyoming includes research into the prehistoric life of the U.S. state of Wyoming as well as investigations conducted by Wyomingite researchers and institutions into ancient life occurring elsewhere.

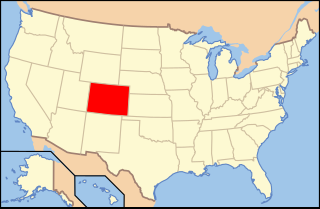

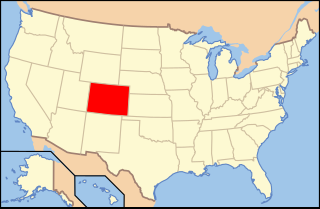

Paleontology in Colorado refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Colorado. The geologic column of Colorado spans about one third of Earth's history. Fossils can be found almost everywhere in the state but are not evenly distributed among all the ages of the state's rocks. During the early Paleozoic, Colorado was covered by a warm shallow sea that would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, conodonts, ostracoderms, sharks and trilobites. This sea withdrew from the state between the Silurian and early Devonian leaving a gap in the local rock record. It returned during the Carboniferous. Areas of the state not submerged were richly vegetated and inhabited by amphibians that left behind footprints that would later fossilize. During the Permian, the sea withdrew and alluvial fans and sand dunes spread across the state. Many trace fossils are known from these deposits.

Paleontology in Utah refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Utah. Utah has a rich fossil record spanning almost all of the geologic column. During the Precambrian, the area of northeastern Utah now occupied by the Uinta Mountains was a shallow sea which was home to simple microorganisms. During the early Paleozoic Utah was still largely covered in seawater. The state's Paleozoic seas would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, fishes, and trilobites. During the Permian the state came to resemble the Sahara desert and was home to amphibians, early relatives of mammals, and reptiles. During the Triassic about half of the state was covered by a sea home to creatures like the cephalopod Meekoceras, while dinosaurs whose footprints would later fossilize roamed the forests on land. Sand dunes returned during the Early Jurassic. During the Cretaceous the state was covered by the sea for the last time. The sea gave way to a complex of lakes during the Cenozoic era. Later, these lakes dissipated and the state was home to short-faced bears, bison, musk oxen, saber teeth, and giant ground sloths. Local Native Americans devised myths to explain fossils. Formally trained scientists have been aware of local fossils since at least the late 19th century. Major local finds include the bonebeds of Dinosaur National Monument. The Jurassic dinosaur Allosaurus fragilis is the Utah state fossil.

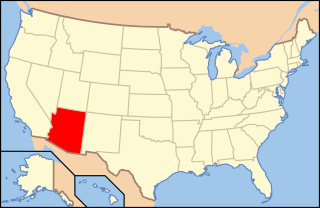

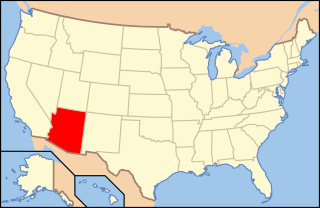

Paleontology in Arizona refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Arizona. The fossil record of Arizona dates to the Precambrian. During the Precambrian, Arizona was home to a shallow sea which was home to jellyfish and stromatolite-forming bacteria. This sea was still in place during the Cambrian period of the Paleozoic era and was home to brachiopods and trilobites, but it withdrew during the Ordovician and Silurian. The sea returned during the Devonian and was home to brachiopods, corals, and fishes. Sea levels began to rise and fall during the Carboniferous, leaving most of the state a richly vegetated coastal plain during the low spells. During the Permian, Arizona was richly vegetated but was submerged by seawater late in the period.

The history of paleontology in the United States refers to the developments and discoveries regarding fossils found within or by people from the United States of America. Local paleontology began informally with Native Americans, who have been familiar with fossils for thousands of years. They both told myths about them and applied them to practical purposes. African slaves also contributed their knowledge; the first reasonably accurate recorded identification of vertebrate fossils in the new world was made by slaves on a South Carolina plantation who recognized the elephant affinities of mammoth molars uncovered there in 1725. The first major fossil discovery to attract the attention of formally trained scientists were the Ice Age fossils of Kentucky's Big Bone Lick. These fossils were studied by eminent intellectuals like France's George Cuvier and local statesmen and frontiersman like Daniel Boone, Benjamin Franklin, William Henry Harrison, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington. By the end of the 18th century possible dinosaur fossils had already been found.

The Bull Run Formation is a Late Triassic (Norian) stratigraphic unit in the eastern United States. Fossil fish bones and scales have been found in outcrops of the formation's Groveton Member in Manassas National Battlefield Park. Indeterminate fossil ornithischian tracks have been reported from the formation.

Burrow fossils are the remains of burrows - holes or tunnels excavated into the ground or seafloor - by animals to create a space suitable for habitation, temporary refuge, or as a byproduct of locomotion preserved in the rock record. Because burrow fossils represent the preserved byproducts of behavior rather than physical remains, they are considered a kind of trace fossil. One common kind of burrow fossil is known as Skolithos, and the similar Trypanites, Ophiomorpha and Diplocraterion.

ReBecca Hunt-Foster is an American paleontologist. She has worked with dinosaur remains from the Late Jurassic to Late Cretaceous of the Colorado Plateau, Rocky Mountains, Southcentral, and the Southwestern United States of America. She described the dinosaur Arkansaurus fridayi and identified the first juvenile Torosaurus occurrences from Big Bend National Park in North America in 2008.

Gwyneddichnium is an ichnogenus from the Late Triassic of North America and Europe. It represents a form of reptile footprints and trackways, likely produced by small tanystropheids such as Tanytrachelos. Gwyneddichnium includes a single species, Gwyneddichnium major. Two other proposed species, G. elongatum and G. minore, are indistinguishable from G. major apart from their smaller size and minor taphonomic discrepancies. As a result, they are considered junior synonyms of G. major.