Related Research Articles

Robert Burnell was an English bishop who served as Lord Chancellor of England from 1274 to 1292. A native of Shropshire, he served as a minor royal official before entering into the service of Prince Edward, the future King Edward I of England. When Edward went on the Eighth Crusade in 1270, Burnell stayed in England to secure the prince's interests. He served as regent after the death of King Henry III of England while Edward was still on crusade. He was twice elected Archbishop of Canterbury, but his personal life—which included a long-term mistress who was rumoured to have borne him four sons—prevented his confirmation by the papacy. In 1275 Burnell was elected Bishop of Bath and Wells, after Edward had appointed him Lord Chancellor in 1274.

A groom or stable boy is a person who is responsible for some or all aspects of the management of horses and/or the care of the stables themselves. The term most often refers to a person who is the employee of a stable owner, but an owner of a horse may perform the duties of a groom, particularly if the owner only possesses a few horses.

Master of the Horse is an official position in several European nations. It was more common when most countries in Europe were monarchies, and is of varying prominence today.

In medieval and early modern Europe, a tenant-in-chief was a person who held his lands under various forms of feudal land tenure directly from the king or territorial prince to whom he did homage, as opposed to holding them from another nobleman or senior member of the clergy. The tenure was one which denoted great honour, but also carried heavy responsibilities. The tenants-in-chief were originally responsible for providing knights and soldiers for the king's feudal army.

A demesne or domain was all the land retained and managed by a lord of the manor under the feudal system for his own use, occupation, or support. This distinguished it from land sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants. In contrast, the entire territory controlled by a monarch both directly and indirectly via their tenant lords would typically be referred to as their realm. The concept originated in the Kingdom of France and found its way to foreign lands influenced by it or its fiefdoms.

Congé d'élire is a licence from the Crown in England issued under the great seal to the dean and chapter of the cathedral church of a diocese, authorizing them to elect a bishop or archbishop, as the case may be, upon the vacancy of any episcopal see in England.

Alien priories were religious establishments in England, such as monasteries and convents, which were under the control of another religious house outside England. Usually the mother-house was in France.

Richard Swinefield was a medieval Bishop of Hereford, England. He graduated doctor of divinity before holding a number of ecclesiastical offices, including that of Archdeacon of London. As a bishop, he dedicated considerable efforts to securing the canonisation of Thomas de Cantilupe, his predecessor, for whom he had worked during his lifetime. Active in his diocese, he devoted little time to politics. He was buried in Hereford Cathedral where a memorial to his memory still stands.

Carucage was a medieval English land tax enacted by King Richard I in 1194, based on the size—variously calculated—of the taxpayer's estate. It was a replacement for the danegeld, last imposed in 1162, which had become difficult to collect because of an increasing number of exemptions. Carucage was levied just six times: by Richard in 1194 and 1198; by John, his brother and successor, in 1200; and by John's son, Henry III, in 1217, 1220, and 1224, after which it was replaced by taxes on income and personal property.

Jura regalia is a medieval legal term which denoted rights that belonged exclusively to the king, either as essential to his sovereignty, such as royal authority; or accidental, such as hunting, fishing and mining rights. Many sovereigns in the Middle Ages and in later times claimed the right to seize the revenues of vacant episcopal sees or abbeys, claiming a regalian right. In some countries, especially in France where it was known as droit de régale, jura regalia came to be applied almost exclusively to that assumed right. A liberty was an area in which the regalian right did not apply.

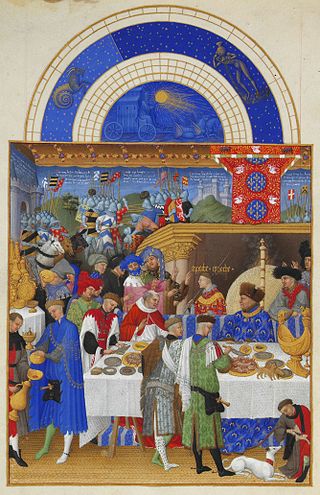

The medieval household was, like modern households, the center of family life for all classes of European society. Yet in contrast to the household of today, it consisted of many more individuals than the nuclear family. From the household of the king to the humblest peasant dwelling, more or less distant relatives and varying numbers of servants and dependents would cohabit with the master of the house and his immediate family. The structure of the medieval household was largely dissolved by the advent of privacy in early modern Europe.

Temporalities or temporal goods are the secular properties and possessions of the church. The term is most often used to describe those properties that were used to support a bishop or other religious person or establishment. Its opposite are spiritualities.

Spiritualities is a term, often used in the Middle Ages, that refers to the income sources of a diocese or other ecclesiastical establishment that came from tithes. It also referred to income that came from other religious sources, such as offerings from church services or ecclesiastical fines.

Translation is the transfer of a bishop from one episcopal see to another. The word is from the Latin trānslātiō, meaning "carry across".

The Close Rolls are an administrative record created in medieval England, Wales, Ireland and the Channel Islands by the royal chancery, in order to preserve a central record of all letters close issued by the chancery in the name of the Crown.

The Constitutio domus regis, was a handbook written around 1136 that discussed the running of the household of King Henry I of England, as it was in the last years of Henry's reign. It was probably written for the new king, Stephen. It gives what every officer and member of the household should be paid, what other allowances they should be given, as well as listing all offices in the household. It is likely that the author of the work was Nigel who was treasurer under Henry I and became Bishop of Ely in 1133, although this is not accepted by all historians.

William de Chesney was a medieval Anglo-Norman nobleman and sheriff. The son of a landholder in Norfolk, William inherited after the death of his two elder brothers. He was the founder of Sibton Abbey, as well as a benefactor of other monasteries in England. In 1157, Chesney acquired the honour of Blythburgh, and was sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk during the 1150s and 1160s. On Chesney's death in 1174, he left three unmarried daughters as his heirs.

Robert fitzRoger was an Anglo-Norman nobleman and Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk and Northumberland. He was a son of Roger fitzRichard and Adelisa de Vere. FitzRoger owed some of his early offices to William Longchamp, but continued in royal service even after the fall of Longchamp. His marriage to an heiress brought him more lands, which were extensive enough for him to be ranked as a baron. FitzRoger founded Langley Abbey in Norfolk in 1195.

Philip de Thaun was the first Anglo-Norman poet. He is the first known poet to write in the Anglo-Norman French vernacular language, rather than Latin. Two poems by him are signed with his name, making his authorship of both clear. A further poem is probably written by him as it bears many writing similarities to his other two poems.

A lunellum is a crescent-shaped knife that was used in medieval times to prepare parchment. The word is derived from the Latin luna (moon) because of its shape. The tool is used for the purpose of scraping off (scudding) remaining tissue from a stretched animal skin that was previously treated, and has its shape to prevent it cutting through the skin.

References

- ↑ Coredon, Christopher and Ann Williams (2004). A Dictionary of Medieval Terms and Phrases. Cambridge. pp. 26–27. ISBN 1-84384-023-5.

- ↑ Thoms, William John (1844). The Book of the Court (2nd ed.). H.G. Bohn. p. 385.

avener history office.

- ↑ Coredon, Christopher and Ann Williams (2004). A Dictionary of Medieval Terms and Phrases. Cambridge. p. 26. ISBN 1-84384-023-5.