Tangaroa is the great atua of the sea, lakes, rivers, and creatures that live within them, especially fish, in Māori mythology. As Tangaroa-whakamau-tai he exercises control over the tides. He is sometimes depicted as a whale.

The Marquesas Islands are a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France in the southern Pacific Ocean. Their highest point is the peak of Mount Oave on Ua Pou island, at 1,230 m (4,035 ft) above sea level.

In Polynesian mythology, Hawaiki is the original home of the Polynesians, before dispersal across Polynesia. It also features as the underworld in many Māori stories.

Sir Jacob Epstein was an American and British sculptor who helped pioneer modern sculpture. He was born in the United States, and moved to Europe in 1902, becoming a British subject in 1910.

Moai or moʻai are monolithic human figures carved by the Rapa Nui people on Rapa Nui in eastern Polynesia between the years 1250 and 1500. Nearly half are still at Rano Raraku, the main moai quarry, but hundreds were transported from there and set on stone platforms called ahu around the island's perimeter. Almost all moai have overly large heads, which account for three-eighths of the size of the whole statue. They also have no legs. The moai are chiefly the living faces of deified ancestors.

A marae, malaʻe, meʻae or malae is a communal or sacred place that serves religious and social purposes in Polynesian societies. In all these languages, the term also means cleared and free of weeds or trees. Marae generally consist of an area of cleared land roughly rectangular, bordered with stones or wooden posts perhaps with paepae (terraces) which were traditionally used for ceremonial purposes; and in some cases, such as Easter Island, a central stone ahu or a'u is placed. In the Easter Island Rapa Nui culture, the term ahu or a'u has become a synonym for the whole marae complex.

Pōmare II, was the second king of Tahiti between 1782 and 1821. He was installed by his father Pōmare I at Tarahoi, 13 February 1791. He ruled under regency from 1791 to 1803.

The Austral Islands are the southernmost group of islands in French Polynesia, an overseas country of the French Republic in the South Pacific. Geographically, they consist of two separate archipelagos, namely in the northwest the Tupua'i islands consisting of the Îles Maria, Rimatara, Rūrutu, Tupua'i Island proper and Ra'ivāvae, and in the southeast the Bass Islands composed of the main island of Rapa Iti and the small Marotiri. Inhabitants of the islands are known for their pandanus fiber weaving skills. The islands of Maria and Marotiri are not suitable for sustained habitation. Several of the islands have uninhabited islets or rocks off their coastlines. Austral Islands' population is 6,965 on almost 150 km2 (58 sq mi). The capital of the Austral Islands administrative subdivision is Tupua'i.

With its 320 square kilometres, Hiva Oa is the second largest island in the Marquesas Islands, in French Polynesia, an overseas territory of France in the Pacific Ocean. Located at 9 45' south latitude and 139 W longitude, it is the largest island of the southern Marquesas group. Around 2,200 people reside on the island. A volcano, Temetiu, is Hiva Oa's highest point with 1,200 metres.

Rimatara is the westernmost inhabited island in the Austral Islands of French Polynesia. It is located 550 km (340 mi) south of Tahiti and 150 km (93 mi) west of Rurutu. The land area of Rimatara is 8.6 km2 (3.3 sq mi), and that of the Maria islets is 1.3 km2 (0.50 sq mi). Its highest point is 106 m (348 ft). Its population was 893 at the 2022 census.

Austral is an endangered Polynesian language or a dialect continuum that was spoken by approximately 8,000 people in 1987 on the Austral Islands and the Society Islands of French Polynesia. The language is also referred to as Tubuai-Rurutu, Tubuai, Rurutu-Tupuai, or Tupuai. It is closely related to other Tahitic languages, most notably Tahitian and Māori.

The Musée de Tahiti et des Îles, Tahitian Te Fare Manaha, is the national museum of French Polynesia, located in Puna'auia, Tahiti.

This page list topics related to French Polynesia.

Wood carving is a common art form in the Cook Islands. Sculpture in stone is much rarer although there are some excellent carvings in basalt by Mike Tavioni. The proximity of islands in the southern group helped produce a homogeneous style of carving but which had special developments in each island. Rarotonga is known for its fisherman's gods and staff-gods, Atiu for its wooden seats, Mitiaro, Mauke and Atiu for mace and slab gods and Mangaia for its ceremonial adzes. Most of the original wood carvings were either spirited away by early European collectors or were burned in large numbers by missionary zealots.

Teriitaria II or Teri'itari'a II, later known as Pōmare Vahine and Ari'ipaea Vahine, baptized Taaroamaiturai, became Queen consort of Tahiti when she married King Pōmare II and later, she ruled as Queen of Huahine and Maiao in the Society Islands.

The Sounion Kouros is an early archaic Greek statue of a naked young man or kouros carved in marble from the island of Naxos around 600 BCE. It is one of the earliest examples that scholars have of the kouros-type which functioned as votive offerings to gods or demi-gods, and were dedicated to heroes. Found near the Temple of Poseidon at Cape Sounion, this kouros was found badly damaged and heavily weathered. It was restored to its original height of 3.05 meters (10.0 ft) returning it to its larger than life size. It is now held by the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

The Deity Figure from Rarotonga is an important wooden sculpture of a male god that was made on the Pacific island of Rarotonga in the Cook Islands. The cult image was given to English missionaries in the early nineteenth century as the local population converted to Christianity. It was eventually bought by the British Museum in 1911.

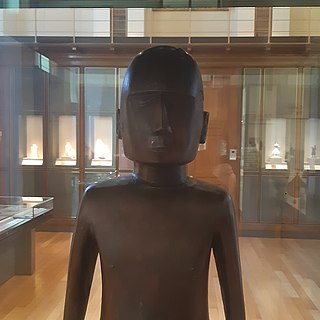

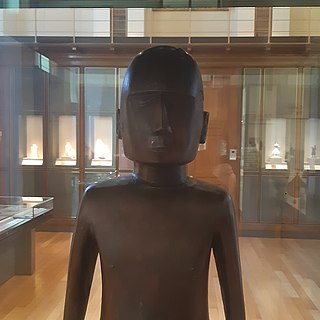

The Mangareva Statue or Deity Figure from Mangareva is a wooden sculpture of a male god that was made on the Pacific island of Mangareva in French Polynesia. The cult image was given to English missionaries in the early nineteenth century as the local population converted to Christianity. It was eventually bought by the British Museum in 1911.

Wood carving in the Marquesas Islands is a practice undertaken by many of the local master craftsmen, who are known as tuhuna. The tuhuna are not only adept at wood carving, but are also skilled at tattoo art and adze manufacture. Marquesan wooden crafts are considered among the finest in French Polynesia; they are highly sought after, and of consistently high quality, although weaving, basket-making, and pareu painting is more popular, especially among women artisans. Paul Gauguin noted the artistic sense of decoration of the Marquesas and appreciated the "unheard of sense of decoration" in their creative art forms.

The Marquesan Dog or Marquesas Islands Dog is an extinct breed of dog from the Marquesas Islands. Similar to other strains of Polynesian dogs, it was introduced to the Marquesas by the ancestors of the Polynesian people during their migrations. Serving as tribal totems and religious symbols, they were sometimes consumed as meat although less frequently than in other parts of the Pacific because of their scarcity. These native dogs are thought to have become extinct before the arrival of Europeans, who did not record their presence on the islands. Petroglyphic representations of dogs and the archaeological remains of dog bones and burials are the only evidence that the breed ever existed. Modern dog populations on the island are the descendants of foreign breeds later reintroduced in the 19th century as companions for European settlers.