A skyscraper is a tall, continuously habitable building having multiple floors. Modern sources currently define skyscrapers as being at least 100 meters (330 ft) or 150 meters (490 ft) in height, though there is no universally accepted definition, other than being very tall high-rise buildings. Historically, the term first referred to buildings with between 10 and 20 stories when these types of buildings began to be constructed in the 1880s. Skyscrapers may host offices, hotels, residential spaces, and retail spaces.

The Chicago School refers to two architectural styles derived from the architecture of Chicago. In the history of architecture, the first Chicago School was a school of architects active in Chicago in the late 19th, and at the turn of the 20th century. They were among the first to promote the new technologies of steel-frame construction in commercial buildings, and developed a spatial aesthetic which co-evolved with, and then came to influence, parallel developments in European Modernism. Much of its early work is also known as Commercial Style.

Tung-Yen Lin was a Chinese-American structural engineer who was the pioneer of standardizing the use of prestressed concrete.

The Garabit viaduct is a railway arch bridge spanning the Truyère, near Ruynes-en-Margeride, Cantal, France, in the mountainous Massif Central region.

Fazlur Rahman Khan was a Bangladeshi-American structural engineer and architect, who initiated important structural systems for skyscrapers. Considered the "father of tubular designs" for high-rises, Khan was also a pioneer in computer-aided design (CAD). He was the designer of the Sears Tower, since renamed Willis Tower, the tallest building in the world from 1973 until 1998, and the 100-story John Hancock Center.

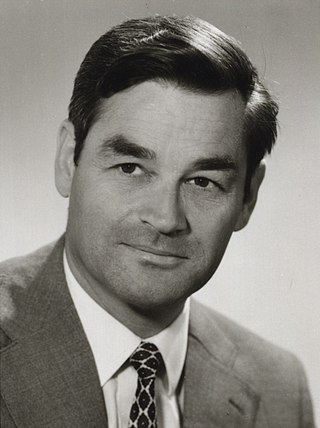

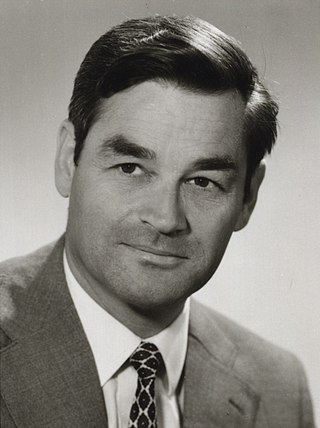

Bruce John Graham was a Colombian-born Peruvian-American architect. Graham built buildings all over the world and was deeply involved with evolving the Burnham Plan of Chicago. Among his most notable buildings are the Inland Steel Building, the Willis Tower, and the John Hancock Center. He was also responsible for planning the Broadgate and Canary Wharf developments in London.

Salginatobel Bridge is a reinforced concrete arch bridge designed by Swiss civil engineer Robert Maillart. It was constructed across an alpine ravine in the grisonian Prättigau, belonging to the municipality of Schiers, in Switzerland between 1929 and 1930. In 1991, it was declared an International Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, the thirteenth such structure and the first concrete bridge so designated.

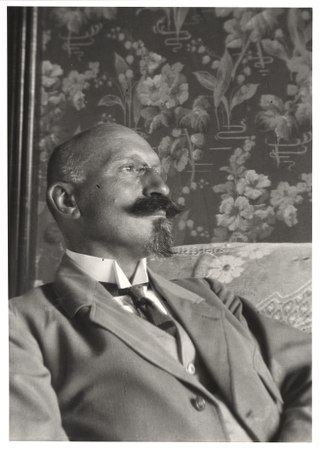

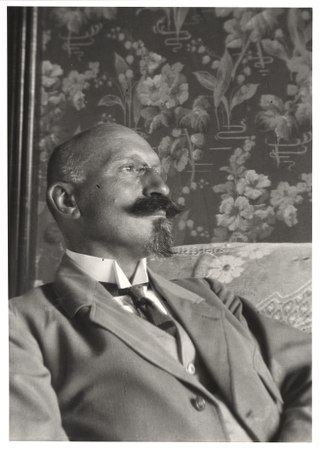

Robert Maillart was a Swiss civil engineer who revolutionized the use of structural reinforced concrete with such designs as the three-hinged arch and the deck-stiffened arch for bridges, and the beamless floor slab and mushroom ceiling for industrial buildings. His Salginatobel (1929–1930) and Schwandbach (1933) bridges changed the aesthetics and engineering of bridge construction dramatically and influenced decades of architects and engineers after him. In 1991 the Salginatobel Bridge was declared an International Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Christian Menn was a renowned Swiss civil engineer and bridge designer. He was involved in the construction of around 100 bridges worldwide, but the focus of his work was in eastern Switzerland, especially in canton Graubünden. He continued the tradition of and had a decisive influence on Swiss bridge building. The technical and aesthetic possibilities of prestressed concrete were most fully realized with his bridges in Switzerland.

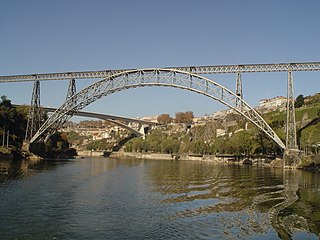

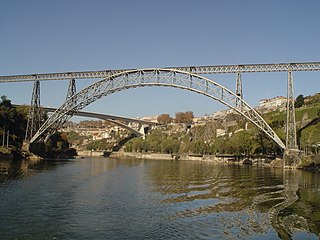

The Maria Pia Bridge is a railway bridge built in 1877, and attributed to Gustave Eiffel, situated over the Portuguese northern municipalities of Porto and Vila Nova de Gaia.

Franz Dischinger was a pioneering German civil and structural engineer, responsible for the development of the modern cable-stayed bridge. He was also a pioneer of the use of prestressed concrete, patenting the technique of external prestressing in 1934.

The Sunniberg Bridge is a curved multi-span extradosed road bridge with low outward-flaring pylons above the roadway edges, designed by the renowned Swiss engineer Christian Menn and completed 1998. It carries the Klosters bypass road 28 across the Landquart River near the village of Klosters in the canton of Grisons in eastern Switzerland. It is notable because of its innovative design and aesthetically pleasing appearance sensitive to its surroundings.

The history of structural engineering dates back to at least 2700 BC when the step pyramid for Pharaoh Djoser was built by Imhotep, the first architect in history known by name. Pyramids were the most common major structures built by ancient civilizations because it is a structural form which is inherently stable and can be almost infinitely scaled.

Earthquake-resistant or aseismic structures are designed to protect buildings to some or greater extent from earthquakes. While no structure can be entirely impervious to earthquake damage, the goal of earthquake engineering is to erect structures that fare better during seismic activity than their conventional counterparts. According to building codes, earthquake-resistant structures are intended to withstand the largest earthquake of a certain probability that is likely to occur at their location. This means the loss of life should be minimized by preventing collapse of the buildings for rare earthquakes while the loss of the functionality should be limited for more frequent ones.

Myron Goldsmith was an American architect and designer. He was a student of Mies van der Rohe and Pier Luigi Nervi before designing 40 projects at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill from 1955 to 1983. His last 16 years at the firm he was a general partner in its Chicago office. His best known project is the McMath–Pierce solar telescope building constructed in 1962 at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona. It is visited by an estimated 100,000 people a year.

The Port à l'Anglais Bridge is a cable-stayed suspension bridge that spans the Seine river between the French communes Alfortville and Vitry-sur-Seine. It carries two lanes of automobile traffic and has pedestrian walkways on each side.

Srinivasa "Hal" Iyengar was an Indian American civil engineer and a senior structural consultant, who has been particularly instrumental in the development of innovative and efficient structural concepts and systems for high-rise, long-span and stadium structures.

Benjamin Recordon was a Swiss architect.

Tavanasa Bridge, also known as Vorderrheinbrücke, Tavanasa is the name of the two reinforced concrete three hinged arch bridges designed by Swiss civil engineer Robert Maillart. The first of these was constructed in 1904, but later destroyed by an avalanche. The second, constructed in 1928 stands to this day.

The Zuoz Bridge, also known as Innbrücke Zuoz is a three hinged reinforced concrete box girder hinged arch bridge designed by Swiss civil engineer Robert Maillart, and is the first box girder bridge to be constructed out of reinforced concrete. Constructed in 1901, this was the first of his independently designed reinforced concrete arch bridges.