Triumph of the Will is a 1935 German Nazi propaganda film directed, produced, edited and co-written by Leni Riefenstahl. Adolf Hitler commissioned the film and served as an unofficial executive producer; his name appears in the opening titles. It chronicles the 1934 Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg, which was attended by more than 700,000 Nazi supporters. The film contains excerpts of speeches given by Nazi leaders at the Congress, including Hitler, Rudolf Hess and Julius Streicher, interspersed with footage of massed Sturmabteilung (SA) and Schutzstaffel (SS) troops and public reaction. Its overriding theme is the return of Germany as a great power with Hitler as its leader. The film was produced after the Night of the Long Knives, and many formerly prominent SA members are absent.

Kolberg is a 1945 Nazi propaganda historical film written and directed by Veit Harlan. One of the last films of the Third Reich, it was intended to bolster the will of the German population to resist the Allies.

The Nazi regime in Germany actively promoted and censored forms of art between 1933 and 1945. Upon becoming dictator in 1933, Adolf Hitler gave his personal artistic preference the force of law to a degree rarely known before. In the case of Germany, the model was to be classical Greek and Roman art, seen by Hitler as an art whose exterior form embodied an inner racial ideal. It was, furthermore, to be comprehensible to the average man. This art was to be both heroic and romantic. The Nazis viewed the culture of the Weimar period with disgust. Their response stemmed partly from conservative aesthetics and partly from their determination to use culture as propaganda.

Nazism made extensive use of the cinema throughout its history. Though it was a relatively new technology, the Nazi Party established a film department soon after it rose to power in Germany. Both Adolf Hitler and his propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, used the many Nazi films to promote the party ideology and show their influence in the burgeoning art form, which was an object of personal fascination for Hitler. The Nazis valued film as a propaganda instrument of enormous power, courting the masses by means of slogans that were aimed directly at the instincts and emotions of the people. The Department of Film also used the economic power of German moviegoers to influence the international film market. This resulted in almost all Hollywood producers censoring films critical of Nazism during the 1930s, as well as showing news shorts produced by the Nazis in American theaters.

The Crew of the Dora is a 1943 German film about Luftwaffe pilots. It depicts a love triangle involving two of them being overcome by their participation in battle together.

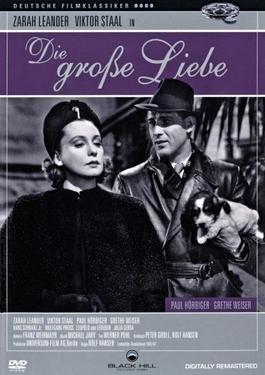

The Great Love is a 1942 German drama film directed by Rolf Hansen and starring Zarah Leander, Viktor Staal and Grethe Weiser. It premiered in Berlin in 1942 and went on to become the most commercially successful film in the history of the Third Reich.

Homecoming is a 1941 Nazi German anti-Polish propaganda film directed by Gustav Ucicky. Filled with heavy-handed caricature, it justifies extermination of Poles with a depiction of relentless persecution of ethnic Germans, who escape death only because of the German invasion.

Refugees is the 1933 German drama film, directed by Gustav Ucicky and starring Hans Albers, Käthe von Nagy, and Eugen Klöpfer. It depicts Volga German refugees persecuted by the Bolsheviks on the Sino-Russian border in Manchuria in 1928.

The Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, also known simply as the Ministry of Propaganda, controlled the content of the press, literature, visual arts, film, theater, music and radio in Nazi Germany.

Wunschkonzert is a 1940 German drama propaganda film by Eduard von Borsody. After Die große Liebe, it was the most popular film of wartime Germany, reaching the second highest gross.

Frisians in Peril is a 1935 German drama film directed by Peter Hagen and starring Friedrich Kayßler, Jessie Vihrog and Valéry Inkijinoff. Made for Nazi propaganda purposes, it concerns a village of ethnic Frisians in Russia.

Unternehmen Michael is a 1937 German film directed by Karl Ritter, the first of three films about the First World War which he made during the period when the Third Reich was rearming.

The Ruler is a 1937 German drama film directed by Veit Harlan. It was adapted from the play of the same name by Gerhart Hauptmann. Erwin Leiser calls it a propagandistic demonstration of the Führerprinzip of Nazi Germany. The film's sets were designed by the art director Robert Herlth. Location shooting took place around Oberhausen and Pompeii near Naples. It premiered at the Ufa-Palast am Zoo in Berlin.

I Accuse is a 1941 Nazi German pro-euthanasia propaganda film directed by Wolfgang Liebeneiner and produced by Heinrich Jonen and Ewald von Demandowsky. It was developed to promote the involuntary euthanasia of disabled people conducted through the Aktion T4 mass murder program and to garner public support for the Nazi concept of life unworthy of life.

Immensee: ein deutsches Volkslied is a German film melodrama of the Nazi era, directed in 1943 by Veit Harlan and loosely based on the popular novella Immensee (1849) by Theodor Storm. It was a commercial success and, with its theme of a woman remaining faithful to her husband, was important in raising the morale of German forces; it remained popular after World War II.

Der Stern von Afrika is a 1957 black-and-white German war film portraying the combat career of a World War II Luftwaffe fighter pilot Hans-Joachim Marseille. The film stars Joachim Hansen and Marianne Koch and was directed by Alfred Weidenmann, whose film career began in the Nazi era.

Karl Ritter was a German film producer and director responsible for many Nazi propaganda films. He had previously been one of the first German military pilots. He spent most of his later life in Argentina.

![<i>Urlaub auf Ehrenwort</i> (1938 film) 1938 [[Nazi Germany]] film](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/4/45/Urlaub_auf_Ehrenwort_%281938%29_poster.jpg)

Urlaub auf Ehrenwort is a 1938 propaganda film directed by Karl Ritter, the last of three films set in the First World War which he made during the period when Nazi Germany was rearming.

Hannes Stelzer was an Austrian film actor. Stelzer was a leading actor in German cinema during the Nazi era.

Pour le Mérite is a 1938 propaganda film produced and directed by Karl Ritter for Nazi Germany. The film follows the story of officers of the Luftstreitkräfte in the First World War who were later involved in the formation of the Luftwaffe. Pour le Mérite propagates the "stab legend", which consigns the German military defeat in World War I to an alleged treason in the homeland. At the same time, Ritter also glorifies the former fighter pilots as heroes of National Socialism.

![<i>Urlaub auf Ehrenwort</i> (1938 film) 1938 [[Nazi Germany]] film](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/4/45/Urlaub_auf_Ehrenwort_%281938%29_poster.jpg)