Biography

Origins and early career

Zaoutzes was of Armenian descent, and was born in the thema of Macedonia. It has been theorized by the historian Nicholas Adontz that Zaoutzes might be the son of a contemporary strategos of Macedonia named Tzantzes, the name also of Zaoutzes's son, but the connection is ultimately impossible to prove. [1] [2] According to Steven Runciman, the surname Zaoutzes derives from the Armenian word Zaoutch, "negro", reflecting Zaoutzes's particularly dark complexion. In the same vein, Zaoutzes was known among Byzantines as "the Ethiopian". [3] Whatever his exact ancestry, he shared ethnic and geographical origin with the Emperor Basil I the Macedonian, a factor that probably played an important role in his ascent to high office during the latter's reign. [2]

In late 882, the young Leo, Basil's second son and heir after the death of his elder brother Constantine in 879, was wedded to Theophano, a member of the Martinakes family. The bride was the choice of empress Eudokia Ingerina, and did not please Leo, who instead preferred the company of Zoe Zaoutzaina, the beautiful daughter of Stylianos Zaoutzes. Whether Zoe was actually his mistress is uncertain; Leo himself strenuously denied this in later accounts. [4] At that point, Zaoutzes held the post of mikros hetaireiarches, i.e. commander of the junior regiment of the Byzantine emperor's mercenary bodyguard, the hetaireia . [5] Leo's relations with his father Basil were always strained, and when Theophano informed him of this affair, Basil reportedly became enraged, beat Leo until he bled, and married Zoe off to one Theodore Gouzouniates. [6] Furthermore, in 883, Leo was denounced as plotting against Basil and was imprisoned; it was only through the intervention of patriarch Photios and Stylianos Zaoutzes that he was not also blinded. [7] This affair does not seem to have hurt Zaoutzes's own standing with Basil or his career, for by the end of Basil's reign he was protospatharios and megas hetaireiarches (senior commander of the hetaireia). [1]

Rise to prominence

Leo spent three years in prison, until released and restored to his rank in late July 886. Here too Zaoutzes played a major role, as he personally pleaded with the Byzantine emperor to secure Leo's release. [8] By that time, Basil was ailing, and on August 12, 886, he was gravely wounded during a hunt. Zaoutzes's participation in the hunt raised suspicions of a conspiracy, but his complicity is generally rejected, as Basil survived for nine days, during which he did not punish Zaoutzes. [9] Upon Basil's death, Leo was crowned emperor, but Zaoutzes, who was awarded the titles of patrikios and magistros and the office of logothetes tou dromou , effectively assumed control of the government, directing state policy. [1] One tradition, based on the Vita Euthymii (the hagiography of Patriarch Euthymios I), holds that Basil himself appointed Zaoutzes as regent (epitropos), but other sources indicate that his ascent to power was more gradual. [10] It is indicative of his authority that most of Leo's ordinances (novels) are directed to him in person, and in 893, he succeeded in getting his protégé, Antony Kauleas, elected as Patriarch of Constantinople. [11] In the same period (between 886 and 893), Emperor Leo VI himself delivered a homily on a church built on Zaoutzes's orders in Constantinople. [12]

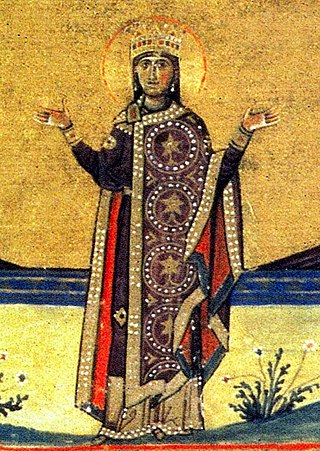

Zaoutzes's rise to prominence was consolidated in 891–893, when he was given the newly created title of basileopator ("father of the emperor"). [13] His promotion to this new and enigmatic title has been a subject of controversy, as neither the reasons for the creation of the title nor its exact functions are known. The early date of his elevation precludes a relation to the eventual rise of his daughter Zoe to the imperial throne as Leo's empress. Gratitude for Zaoutzes's support against Basil may have played a role, and a common theory is that the office implied some form of tutorship over the emperor. [14] The office certainly confirmed Zaoutzes as the senior secular official of the Byzantine Empire. However, although Zaoutzes has traditionally been regarded as an all-powerful regent over a weak emperor, in no small part due to the account provided in the Vita Euthymii, the actual relationship between the two may have been quite different. A more careful evaluation of the source material has led modern scholarship to conclude that Leo was actively involved in government, and that Zaoutzes as chief minister was loyal and obsequious to his master. [15]

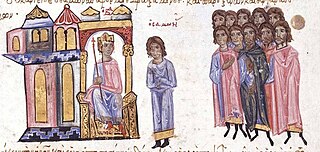

An assessment of his record as the Byzantine Empire's first minister is difficult. Of the few available sources on his career, the Vita Euthymii, compiled years after Zaoutzes's death, is extremely hostile, seeking to pin the responsibility for several of the reign's failures or unpopular decisions on him, and thus preserve Leo from blame. [16] The account of the Vita is further colored by the fierce rivalry between Zaoutzes and Euthymios, then a synkellos and Leo's spiritual father, over influence on the Byzantine emperor. [17] Thus the Vita accuses Zaoutzes of being responsible for the sacking of the successful general Nikephoros Phokas the Elder from the army, as well as for the outbreak of hostilities with Bulgaria in 893: allegedly, two of his protégés moved the main market for Bulgarian goods from Constantinople to Thessalonica and then proceeded to extract exorbitant fees from the Bulgarian merchants. When Leo, at the behest of Zaoutzes, rejected the merchants' protests, the Bulgarian Tsar Simeon I found a pretext to attack Byzantium. [1] [18] It has, however, been recently suggested by the scholar Paul Magdalino that the transfer was in fact Leo's initiative, aiming to enrich Thessalonica, whose patron saint, Saint Demetrius, he showed special favor to. [19]

Fall from favor and death

Nevertheless, all this has led to the enduring image of an ineffectual leadership in foreign and military affairs under Zaoutzes. [20] This may explain why, despite the resumption of Leo's affair with Zoe, the relationship between Zaoutzes and the emperor became strained: tales of an alleged plot by Zaoutzes's son to murder Leo in 894/895 indicate a rift between the two, and although Zaoutzes himself was not involved, a major quarrel between them ensued shortly after. [21] Although they were reconciled, Zaoutzes's standing seems to have declined further thereafter, as two of his protégés, found guilty of accepting bribes, were punished by Leo. [22] Nevertheless, in late summer 898, following the death of Theophano on 10 November 897, and of Zoe's first husband Gouzouniates in early 898, Leo at last married Zoe, raising her to Augusta . In the next year, however, both Zoe and Stylianos died. [23] Following their deaths, Leo proposed to marry yet again, choosing Eudokia Baïana as his wife. Zaoutzes's numerous relatives, who had benefited from his patronage, were fearful of losing their positions to the new Empress's relations, and conspired to overthrow Leo. Chief among them was Basil, Zoe's nephew. The plot, however, was betrayed by the eunuch servant Samonas, and the conspiracy suppressed. The Zaoutzes relatives were exiled or confined to monasteries, and the clan's power broken. [1] [24] Samonas himself was richly rewarded: he was taken into the imperial service and rapidly promoted, becoming parakoimomenos by 908, before he too fell from favor. [25]