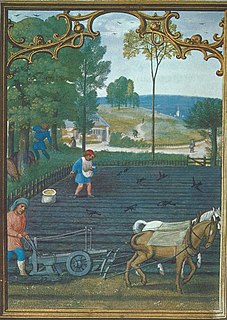

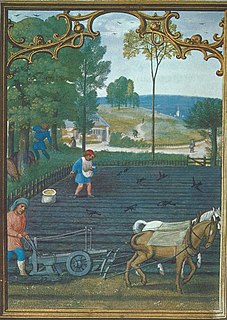

A plough or plow is a farm tool for loosening or turning the soil before sowing seed or planting. Ploughs were traditionally drawn by oxen and horses, but in modern farms are drawn by tractors. A plough may have a wooden, iron or steel frame, with a blade attached to cut and loosen the soil. It has been fundamental to farming for most of history. The earliest ploughs had no wheels; such a plough was known to the Romans as an aratrum. Celtic peoples first came to use wheeled ploughs in the Roman era.

The modern combine harvester, or simply combine, is a versatile machine designed to efficiently harvest a variety of grain crops. The name derives from its combining four separate harvesting operations—reaping, threshing, gathering, and winnowing— to a single process. Among the crops harvested with a combine are wheat, rice, oats, rye, barley, corn (maize), sorghum, soybeans, flax (linseed), sunflowers and rapeseed. The separated straw, left lying on the field, comprises the stems and any remaining leaves of the crop with limited nutrients left in it: the straw is then either chopped, spread on the field and ploughed back in or baled for bedding and limited-feed for livestock.

A reaper is a farm implement or person that reaps crops at harvest when they are ripe. Usually the crop involved is a cereal grass. The first documented reaping machines were Gallic reapers that were used in Roman times in what would become modern-day France. The Gallic reaper involved a comb which collected the heads, with an operator knocking the grain into a box for later threshing.

Threshing, or thrashing, is the process of loosening the edible part of grain from the straw to which it is attached. It is the step in grain preparation after reaping. Threshing does not remove the bran from the grain.

Ridge and furrow is an archaeological pattern of ridges and troughs created by a system of ploughing used in Europe during the Middle Ages, typical of the open-field system. It is also known as rigand furrow, mostly in the North East of England and in Scotland.

An ox, also known as a bullock, is a male bovine trained and used as a draft animal. Oxen are commonly castrated adult male cattle; castration inhibits testosterone and aggression, which makes the males docile and safer to work with. Cows or bulls may also be used in some areas.

In ancient Greece, the Buphonia denoted a sacrificial ceremony performed at Athens as part of the Dipolieia, a religious festival held on the 14th of the midsummer month Skirophorion— in June or July— at the Acropolis. In the Buphonia a working ox was sacrificed to Zeus Polieus, Zeus protector of the city, in accordance with a very ancient custom. A group of oxen was driven forward to the altar at the highest point of the Acropolis. On the altar a sacrifice of grain had been spread by members of the family of the Kentriadae, on whom this duty devolved hereditarily. When one of the oxen began to eat, thus selecting itself for sacrifice, one of the family of the Thaulonidae advanced with an axe, slayed the ox, then immediately threw aside the axe and fled the scene of his guilt-laden crime.

A stook /stʊk/, also referred to as a shock or stack, is an arrangement of sheaves of cut grain-stalks placed so as to keep the grain-heads off the ground while still in the field and before collection for threshing. Stooked grain sheaves are typically wheat, barley and oats. In the era before combine harvesters and powered grain driers, stooking was necessary to dry the grain for a period of days to weeks before threshing, to achieve a moisture level low enough for storage. In the 21st century, most grain is produced with the mechanized and powered methods, and is therefore not stooked at all. However, stooking remains useful to smallholders who grow their own grain, or at least some of it, as opposed to buying it.

The ard, ard plough, or scratch plough is a simple light plough without a mouldboard. It is symmetrical on either side of its line of draft and is fitted with a symmetrical share that traces a shallow furrow but does not invert the soil. It began to be replaced in China by the heavy carruca turnplough in the 1st century, and in most of Europe from the 7th century.

Threshing (thrashing) was originally "to tramp or stamp heavily with the feet" and was later applied to the act of separating out grain by the feet of people or oxen and still later with the use of a flail. A threshing floor is of two main types: 1) a specially flattened outdoor surface, usually circular and paved, or 2) inside a building with a smooth floor of earth, stone or wood where a farmer would thresh the grain harvest and then winnow it. Animal and steam powered threshing machines from the nineteenth century onward made threshing floors obsolete. The outdoor threshing floor was either owned by the entire village or by a single family, and it was usually located outside the village in a place exposed to the wind.

A threshing board, also known as threshing sledge, is an obsolete agricultural implement used to separate cereals from their straw; that is, to thresh. It is a thick board, made with a variety of slats, with a shape between rectangular and trapezoidal, with the frontal part somewhat narrower and curved upward and whose bottom is covered with lithic flakes or razor-like metal blades.

The Royal Ploughing Ceremony, also known as The Ploughing Festival, is an ancient royal rite held in many Asian countries to mark the traditional beginning of the rice growing season. The royal ploughing ceremony, called Lehtun Mingala or Mingala Ledaw (မင်္ဂလာလယ်တော်), was also practiced in pre-colonial Burma until 1885 when the monarchy was abolished

The Chinese poet Yao Shouzhong 姚守中 is thought to have been from the city of Luoyang 洛陽 in present Henan 河南. His dates are unclear. However, he seems to have been the nephew of the writer and official Yao Sui 姚燧 who lived from 1238 to 1313. Yao Shouzhong would then have lived in the early 14th century. Likewise, this Yao Sui was himself the nephew of the celebrated official and scholar Yao Shu (1203–1280). The greater family had its origins in the Manchurian province of Liaoning and later moved to Luoyang. Yao Shouzhong appears to have been a local official functionary in Pingjiang in Hunan. The Lu Guibu 彔鬼簿 notes only that Yao was a literary talent from the previous generation. "The Ox’s Grievance" 牛訴冤 is the only surviving literary work of the writer, although titles of the three of his plays have survived. Tao’s Sanqu suite, "The Ox’s Grievance", is a classic of the genre and is one of the great imaginative poems in the genre of Chinese Sanqu poetry and Chinese literature as a whole. Although it has been suggested that "The Ox's Grievance" is a social satire, more likely it was intended as a literary burlesque or parody.

Agricultural machinery relates to the mechanical structures and devices used in farming or other agriculture. There are many types of such equipment, from hand tools and power tools to tractors and the countless kinds of farm implements that they tow or operate. Diverse arrays of equipment are used in both organic and nonorganic farming. Especially since the advent of mechanised agriculture, agricultural machinery is an indispensable part of how the world is fed.

The Debate between Winter and Summer or Myth of Emesh and Enten is a Sumerian creation myth, written on clay tablets in the mid to late 3rd millennium BC.

Ur-Ninurta, c. 1859 – 1832 BC or c. 1923 – 1896 BC, was the 6th king of the 1st Dynasty of Isin. A usurper, Ur-Ninurta seized the throne on the fall of Lipit-Ištar and held it until his violent death some 28 years later.

Agriculture in the Middle Ages describes the farming practices, crops, technology, and agricultural society and economy of Europe from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 to approximately 1500. The Middle Ages are sometimes called the Medieval Age or Period. The Middle Ages are also divided into the Early, High, and Late Middle Ages. The early modern period followed the Middle Ages.

Ruth 3 is the third chapter of the Book of Ruth in the Hebrew Bible or the Old Testament of the Christian Bible, part of the Ketuvim ("Writings"). This chapter contains the story of how on Naomi's advice, Ruth slept at Boaz's feet, Ruth 3:1-7; Boaz commends what she had done, and acknowledges the right of a kinsman; tells her there was a nearer kinsman, to whom he would offer her, and if that man refuses, Boaz would redeem her, Ruth 3:8-13; Boaz sends her away with six measures of barley, Ruth 3:14-18.

Agriculture is the ratio main economic activity in ancient Mesopotamia. Operating under harsh constraints, notably the arid climate, the Mesopotamian farmers developed effective strategies that enabled them to support the development of the first states, the first cities, and then the first known empires, under the supervision of the institutions which dominated the economy: the royal and provincial palaces, the temples, and the domains of the elites. They focused above all on the cultivation of cereals and sheep farming, but also farmed legumes, as well as date palms in the south and grapes in the north.

This glossary of agriculture is a list of definitions of terms and concepts used in agriculture, its sub-disciplines, and related fields. For other glossaries relevant to agricultural science, see Glossary of biology, Glossary of ecology, Glossary of environmental science, and Glossary of botany.