Related Research Articles

A social norm is a shared standard of acceptable behavior by a group. Social norms can both be informal understandings that govern the behavior of members of a society, as well as be codified into rules and laws. Social normative influences or social norms, are deemed to be powerful drivers of human behavioural changes and well organized and incorporated by major theories which explain human behaviour. Institutions are composed of multiple norms. Norms are shared social beliefs about behavior; thus, they are distinct from "ideas", "attitudes", and "values", which can be held privately, and which do not necessarily concern behavior. Norms are contingent on context, social group, and historical circumstances.

Rationality is the quality of being guided by or based on reason. In this regard, a person acts rationally if they have a good reason for what they do, or a belief is rational if it is based on strong evidence. This quality can apply to an ability, as in a rational animal, to a psychological process, like reasoning, to mental states, such as beliefs and intentions, or to persons who possess these other forms of rationality. A thing that lacks rationality is either arational, if it is outside the domain of rational evaluation, or irrational, if it belongs to this domain but does not fulfill its standards.

A role is a set of connected behaviors, rights, obligations, beliefs, and norms as conceptualized by people in a social situation. It is an expected or free or continuously changing behavior and may have a given individual social status or social position. It is vital to both functionalist and interactionist understandings of society. Social role theory posits the following about social behavior:

- The division of labour in society takes the form of the interaction among heterogeneous specialized positions, we call roles.

- Social roles included appropriate and permitted forms of behavior and actions that recur in a group, guided by social norms, which are commonly known and hence determine the expectations for appropriate behavior in these roles, which further explains the position of a person in the society.

- Roles are occupied by individuals, who are called actors.

- When individuals approve of a social role, they will incur costs to conform to role norms, and will also incur costs to punish those who violate role norms.

- Changed conditions can render a social role outdated or illegitimate, in which case social pressures are likely to lead to role change.

- The anticipation of rewards and punishments, as well as the satisfaction of behaving pro-socially, account for why agents conform to role requirements.

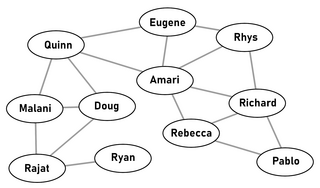

In the social sciences, a social group is defined as two or more people who interact with one another, share similar characteristics, and collectively have a sense of unity. Regardless, social groups come in a myriad of sizes and varieties. For example, a society can be viewed as a large social group. The system of behaviors and psychological processes occurring within a social group or between social groups is known as group dynamics.

Team building is a collective term for various types of activities used to enhance social relations and define roles within teams, often involving collaborative tasks. It is distinct from team training, which is designed by a combination of business managers, learning and development/OD and an HR Business Partner to improve the efficiency, rather than interpersonal relations.

In philosophy of mind and cognitive science, folk psychology, or commonsense psychology, is a human capacity to explain and predict the behavior and mental state of other people. Processes and items encountered in daily life such as pain, pleasure, excitement, and anxiety use common linguistic terms as opposed to technical or scientific jargon. Folk psychology allows for an insight into social interactions and communication, thus stretching the importance of connection and how it is experienced.

An attitude "is a summary evaluation of an object of thought. An attitude object can be anything a person discriminates or holds in mind." Attitudes include beliefs (cognition), emotional responses (affect) and behavioral tendencies. In the classical definition an attitude is persistent, while in more contemporary conceptualizations, attitudes may vary depending upon situations, context, or moods.

A prescriptive or normative statement is one that evaluates certain kinds of words, decisions, or actions as either correct or incorrect, or one that sets out guidelines for what a person "should" do.

In the social sciences, social structure is the aggregate of patterned social arrangements in society that are both emergent from and determinant of the actions of individuals. Likewise, society is believed to be grouped into structurally related groups or sets of roles, with different functions, meanings, or purposes. Examples of social structure include family, religion, law, economy, and class. It contrasts with "social system", which refers to the parent structure in which these various structures are embedded. Thus, social structures significantly influence larger systems, such as economic systems, legal systems, political systems, cultural systems, etc. Social structure can also be said to be the framework upon which a society is established. It determines the norms and patterns of relations between the various institutions of the society.

Credibility comprises the objective and subjective components of the believability of a source or message. Credibility dates back to Aristotle theory of Rhetoric. Aristotle defines rhetoric as the ability to see what is possibly persuasive in every situation. He divided the means of persuasion into three categories, namely Ethos, Pathos, and Logos, which he believed have the capacity to influence the receiver of a message. According to Aristotle, the term "Ethos" deals with the character of the speaker. The intent of the speaker is to appear credible. In fact, the speaker's ethos is a rhetorical strategy employed by an orator whose purpose is to "inspire trust in his audience". Credibility has two key components: trustworthiness and expertise, which both have objective and subjective components. Trustworthiness is based more on subjective factors, but can include objective measurements such as established reliability. Expertise can be similarly subjectively perceived, but also includes relatively objective characteristics of the source or message. Secondary components of credibility include source dynamism (charisma) and physical attractiveness.

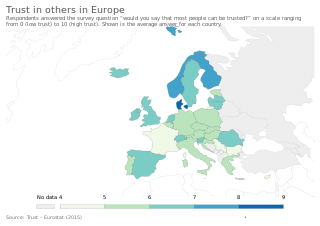

Trust is the belief that another person will do what is expected. It brings with it a willingness for one party to become vulnerable to another party, on the presumption that the trustee will act in ways that benefit the trustor. In addition, the trustor does not have control over the actions of the trustee. Scholars distinguish between generalized trust, which is the extension of trust to a relatively large circle of unfamiliar others, and particularized trust, which is contingent on a specific situation or a specific relationship.

The theory of planned behaviour (TPB) is a psychological theory that links beliefs to behavior. The theory maintains that three core components, namely, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control, together shape an individual's behavioral intentions. In turn, a tenet of TPB is that behavioral intention is the most proximal determinant of human social behavior.

The theory of reasoned action aims to explain the relationship between attitudes and behaviors within human action. It is mainly used to predict how individuals will behave based on their pre-existing attitudes and behavioral intentions. An individual's decision to engage in a particular behavior is based on the outcomes the individual expects will come as a result of performing the behavior. Developed by Martin Fishbein and Icek Ajzen in 1967, the theory derived from previous research in social psychology, persuasion models, and attitude theories. Fishbein's theories suggested a relationship between attitude and behaviors. However, critics estimated that attitude theories were not proving to be good indicators of human behavior. The TRA was later revised and expanded by the two theorists in the following decades to overcome any discrepancies in the A–B relationship with the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and reasoned action approach (RAA). The theory is also used in communication discourse as a theory of understanding.

In ethics and social sciences, value denotes the degree of importance of some thing or action, with the aim of determining which actions are best to do or what way is best to live, or to describe the significance of different actions. Value systems are proscriptive and prescriptive beliefs; they affect the ethical behavior of a person or are the basis of their intentional activities. Often primary values are strong and secondary values are suitable for changes. What makes an action valuable may in turn depend on the ethical values of the objects it increases, decreases, or alters. An object with "ethic value" may be termed an "ethic or philosophic good".

Greenberg (1987) introduced the concept of organizational justice with regard to how an employee judges the behavior of the organization and the employee's resulting attitude and behaviour. For example, if a firm makes redundant half of the workers, an employee may feel a sense of injustice with a resulting change in attitude and a drop in productivity.

Counterproductive norms are group norms that prevent a group, organization, or other collective entities from performing or accomplishing its originally stated function by working oppositely to how they were initially intended. Group norms are typically enforced to facilitate group survival, to make group member behaviour predictable, to help avoid embarrassing interpersonal interactions, or to clarify distinctive aspects of the group’s identity. Counterproductive norms exist despite the fact that they cause opposite outcomes of the intended prosocial functions.

The social identity model of deindividuation effects is a theory developed in social psychology and communication studies. SIDE explains the effects of anonymity and identifiability on group behavior. It has become one of several theories of technology that describe social effects of computer-mediated communication.

Organizational identification (OI) is a term used in management studies and organizational psychology. The term refers to the propensity of a member of an organization to identify with that organization. OI has been distinguished from "affective organizational commitment". Measures of an individual's OI have been developed, based on questionnaires.

Conformity is the act of matching attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors to group norms, politics or being like-minded. Norms are implicit, specific rules, guidance shared by a group of individuals, that guide their interactions with others. People often choose to conform to society rather than to pursue personal desires – because it is often easier to follow the path others have made already, rather than forging a new one. Thus, conformity is sometimes a product of group communication. This tendency to conform occurs in small groups and/or in society as a whole and may result from subtle unconscious influences, or from direct and overt social pressure. Conformity can occur in the presence of others, or when an individual is alone. For example, people tend to follow social norms when eating or when watching television, even if alone.

Cross-cultural psychology attempts to understand how individuals of different cultures interact with each other. Along these lines, cross-cultural leadership has developed as a way to understand leaders who work in the newly globalized market. Today's international organizations require leaders who can adjust to different environments quickly and work with partners and employees of other cultures. It cannot be assumed that a manager who is successful in one country will be successful in another.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Meyerson, D., Weick, K. E., & Kramer, R. M. (1996). Swift trust and temporary groups. In Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- ↑ Costa, A. C. (2003). Work team trust and effectiveness. Personnel review, 32 (5), 605-622.

- ↑ Langfred, C. (2004). Too much of a good thing? Negative effects of high trust and individual autonomy in self-managing teams. Academy of Management journal, 47 (3), 385.

- 1 2 3 4 Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., & LePine, J. A. (2007). Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: a meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 909.

- ↑ Shapiro, D. L., Sheppard, B. H., Charaskin, L. (1992). "Business on a Handshake," Negotiation Journal, 8, 365-77 doi : 10.1111/j.1571-9979.1992.tb00679.x

- ↑ Luhmann, N. (1979), Trust and Power. New York: Wiley & Sons Inc.

- 1 2 Jarvenpaa, S. L., Shaw, T. R., & Staples, D. (2004). Toward contextualized theories of trust: The role of trust in global virtual teams. Information Systems Research, 15(3), 250-264.doi:10.1287/isre.1040.0028

- ↑ Bhattacharya, A. (1998). Formal Model of Trust Based on Outcomes. The Academy of Management review, 23 (3), 459–472

- ↑ Mayer, R. C., Davis, J., H., & Schoorman, D. F., An integrative model of trust. The Academy of Management review, 20 (3), 459-472

- 1 2 Kohler, T., Cortina, J. M., Salas, E., & Garven, A. J., (2011). Trust in temporary work groups. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Management and Marketing, The University of Melbourne.

- 1 2 McKnight, D. H. (1998). Initial trust formation in new organizational relationships. (Special Topic Forum on Trust in and Between Organizations). The Academy of Management review, 23 (3), 473.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Crisp, C. B. & Jarvenpaa, S.L., (2013). Swift trust in global virtual teams trusting beliefs and normative actions. Journal of personnel psychology, 12 (1), 45-56.

- ↑ Hogg, M. A., Terry, D. J. (2000). Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. The Academy of Management review, 25 (1), 121–140.

- ↑ Cialdini, R. B., & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity, and compliance. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The Handbook of Social Psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 151–192). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Postmes, T., Spears, R., & Lea, M. (2000). The formation of group norms in computer-mediated communication. Human Communication Research, 26, 341–371.

- ↑ Ehrhart, M.G., & Naumann, S.E. (2004). Organizational citizenship behavior in work groups: A group norms approach.. Journal of Applied Psychology. 89 (6), 960–974.

- ↑ Kristof, A. L., Brown, K. G., Sims, H. P., Smith, K. A. (1995). The virtual team: A case study and inductive model. Beyerlein, M. M., Johnshon, D. A., Beyerlein, S. T., eds. Advances in Interdisciplinary Studies of Work Teams: Knowledge Work in Teams, Vol. 2. JAI Press, Greenwich, CT, 229–253.

- ↑ 4. Wengel, J. (2023)

- ↑ 4. Wengel, J. (2023)

- ↑ Wildman, J. L. (2012). Trust Development in Swift Starting Action Teams: A Multilevel Framework. Group & organization management, 37 (2), 137–170.

- ↑ Jarvenpaa, S. L., & Leidner, D. E. (1998). Communication and trust in global virtual teams. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 3 (4), 1–36.