The Pietà is a subject in Christian art depicting the Blessed Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus Christ after his Descent from the Cross. It is most often found in sculpture. The Pietà is a specific form of the Lamentation of Christ in which Jesus is mourned by the Virgin Mary alone. However, in practice works called a Pietà may include angels, the other figures usual in Lamentations, and even donor portraits.

The Descent from the Cross, or Deposition of Christ, is the scene, as depicted in art, from the Gospels' accounts of Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus taking Christ down from the cross after his crucifixion. In Byzantine art the topic became popular in the 9th century, and in the West from the 10th century. The Descent from the Cross is the 13th Station of the Cross, and is also the sixth of the Seven Sorrows of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Christ Falling on the Way to Calvary, also known as Lo Spasimo or Il Spasimo di Sicilia, is a painting by the Italian High Renaissance painter Raphael, of c. 1514–16, now in the Museo del Prado in Madrid. It is an important work for the development of his style.

The Descent from the Cross is the central panel of a triptych painting by the Baroque artist Peter Paul Rubens in 1612–1614. It is still in its original place, the Cathedral of Our Lady, Antwerp, Belgium. The painting is considered to be one of Rubens' masterpieces. The painting depicts the moment when the body of Jesus Christ is taken down from the cross after his crucifixion. The subject was one Rubens returned to again and again in his career. The artwork was commissioned on September 7, 1611, by the Confraternity of the Arquebusiers, whose patron saint was St. Christopher.

Christ Carrying the Cross on his way to his crucifixion is an episode included in the Gospel of John, and a very common subject in art, especially in the fourteen Stations of the Cross, sets of which are now found in almost all Roman Catholic churches, as well as in many Lutheran churches and Anglican churches. However, the subject occurs in many other contexts, including single works and cycles of the Life of Christ or the Passion of Christ. Alternative names include the Procession to Calvary, Road to Calvary and Way to Calvary, Calvary or Golgotha being the site of the crucifixion outside Jerusalem. The actual route taken is defined by tradition as the Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem, although the specific path of this route has varied over the centuries and continues to be the subject of debate.

The Nativity of Jesus has been a major subject of Christian art since the 4th century.

The circumcision of Jesus is an event from the life of Jesus, according to the Gospel of Luke chapter 2, which states:

And when eight days were fulfilled to circumcise the child, his name was called Jesus, the name called by the angel before he was conceived in the womb.

The Life of the Virgin, showing narrative scenes from the life of Mary, the mother of Jesus, is a common subject for pictorial cycles in Christian art, often complementing, or forming part of, a cycle on the Life of Christ. In both cases the number of scenes shown varies greatly with the space available. Works may be in any medium: frescoed church walls and series of old master prints have many of the fullest cycles, but panel painting, stained glass, illuminated manuscripts, tapestries, stone sculptures and ivory carvings have many examples.

The Flagellation of Christ, in art sometimes known as Christ at the Column or the Scourging at the Pillar, is an episode from the Passion of Jesus as presented in the Gospels. As such, it is frequently shown in Christian art, in cycles of the Passion or the larger subject of the Life of Christ. Catholic tradition places the Flagellation on the site of the Church of the Flagellation (the second station of the Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem. It is the second Sorrowful Mystery of the Rosary and the sixth station of the John Paul II’s Scriptural Way of the Cross. The column to which Christ is normally shown to be tied, and the rope, scourge, whip or birch are elements in the Arma Christi. The Basilica di Santa Prassede in Rome is one of the churches claiming to possess the original column or parts of it.

Joannes Molanus (1533–1585), often cited simply as Molanus, is the Latinized name of Jan Vermeulen or Van der Meulen, an influential Counter Reformation Catholic theologian of Louvain University, where he was Professor of Theology, and Rector from 1578. Born at Lille, he was a priest and canon of St. Peter's Church, Leuven, where he died.

The Lamentation of Christ is a very common subject in Christian art from the High Middle Ages to the Baroque. After Jesus was crucified, his body was removed from the cross and his friends mourned over his body. This event has been depicted by many different artists.

The life of Christ as a narrative cycle in Christian art comprises a number of different subjects showing events from the life of Jesus on Earth. They are distinguished from the many other subjects in art showing the eternal life of Christ, such as Christ in Majesty, and also many types of portrait or devotional subjects without a narrative element.

The Descent from the Cross is a panel painting by the Flemish artist Rogier van der Weyden created c. 1435, now in the Museo del Prado, Madrid. The crucified Christ is lowered from the cross, his lifeless body held by Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus.

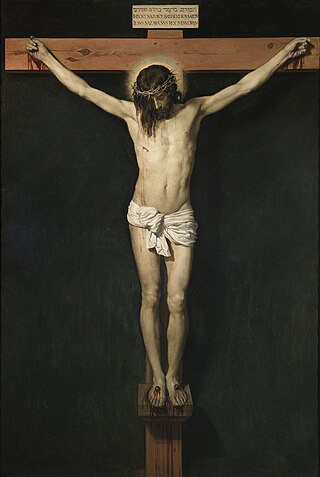

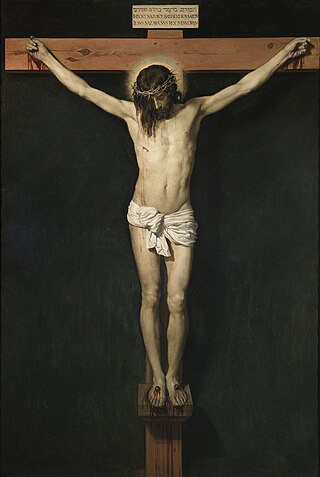

The crucifixion of Jesus was the violent death of Jesus by nailing him to a wooden cross. It happened in 1st-century Judaea, most likely in AD 30 or AD 33. It is described in the four canonical gospels, referred to in the New Testament epistles, later attested to by other ancient sources, and is broadly accepted as one of the events to have most likely occurred during his life. There is no consensus among historians on the details.

Crucifixions and crucifixes have appeared in the arts and popular culture from before the era of the pagan Roman Empire. The crucifixion of Jesus has been depicted in a wide range of religious art since the 4th century CE, frequently including the appearance of mournful onlookers such as the Virgin Mary, Pontius Pilate, and angels, as well as antisemitic depictions portraying Jews as responsible for Christ's death. In more modern times, crucifixion has appeared in film and television as well as in fine art, and depictions of other historical crucifixions have appeared as well as the crucifixion of Christ. Modern art and culture have also seen the rise of images of crucifixion being used to make statements unconnected with Christian iconography, or even just used for shock value.

Stabat Mater is a compositional form in the crucifixion of Jesus in art depicting the Virgin Mary under the cross during the crucifixion of Christ alongside John the apostle.

Santa Maria dello Spasimo, or Lo Spasimo, is an unfinished Catholic church in the Kalsa neighborhood in Palermo, Sicily, on Via dello Spasimo.

Crucifixion Diptych — also known as Philadelphia Diptych, Calvary Diptych, Christ on the Cross with the Virgin and St. John, or The Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist Mourning — is a diptych by the Early Netherlandish artist Rogier van der Weyden, completed c. 1460, today in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The panels are noted for their technical skill, visceral impact and for possessing a physicality and directness unusual for Netherlandish art of the time. The Philadelphia Museum of Art describes this work as the "greatest Old Master painting in the Museum."

The Christ and the Virgin Diptych consisted of two small oil on oak panel paintings by the Early Netherlandish painter Dirk Bouts completed c. 1470–1475. Originally they formed the wings of a hinged devotional diptych.

The Annunciation is an oil painting by the Early Netherlandish painter Hans Memling. It depicts the Annunciation, the archangel Gabriel's announcement to the Virgin Mary that she would conceive and become the mother of Jesus, described in the Gospel of Luke. The painting was executed in the 1480s and was transferred to canvas from its original oak panel sometime after 1928; it is today held in the Robert Lehman collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.