Related Research Articles

The Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 47 of Jean Sibelius, originally composed in 1904 and revised in 1905, is the only concerto by Sibelius. It is symphonic in scope and included an extended cadenza for the soloist that takes on the role of the development section in the first movement.

Concerto in F is a composition by George Gershwin for solo piano and orchestra which is closer in form to a traditional concerto than his earlier jazz-influenced Rhapsody in Blue. It was written in 1925 on a commission from the conductor and director Walter Damrosch. A full performance lasts around half an hour.

The Cello Concerto No. 1 in E-flat major, Op. 107, was composed in 1959 by Dmitri Shostakovich. Shostakovich wrote the work for his friend Mstislav Rostropovich, who committed it to memory in four days. He premiered it on October 4, 1959, at the Large Hall of the Leningrad Conservatory with the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Yevgeny Mravinsky. The first recording was made in two days following the premiere by Rostropovich and the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Aleksandr Gauk.

Sergei Prokofiev wrote his Symphony No. 3 in C minor, Op. 44, in 1928.

Sergei Prokofiev's Symphony No. 4 is actually two works, both using material created for The Prodigal Son ballet. The first, Op. 47, was completed in 1930 and premiered that November; it lasts about 22 minutes. The second, Op. 112, is too different to be termed a "revision"; made in 1947, it is about 37 minutes long, differs stylistically from the earlier work, reflecting a new context, and differs formally as well in its grander instrumentation.

The Symphony No. 7 in C major, Op. 105, is a single-movement work for orchestra written from 1914 to 1924 by the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius.

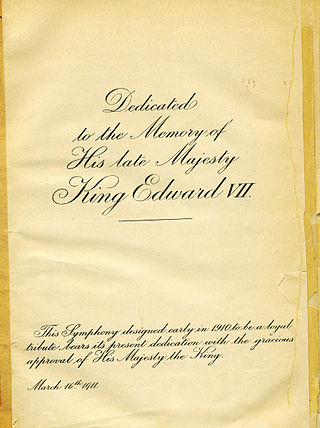

Sir Edward Elgar's Symphony No. 2 in E♭ major, Op. 63, was completed on 28 February 1911 and was premiered at the London Musical Festival at the Queen's Hall by the Queen's Hall Orchestra on 24 May 1911 with the composer conducting. The work, which Elgar called "the passionate pilgrimage of the soul", was his last completed symphony; the composition of his Symphony No. 3, begun in 1933, was cut short by his death in 1934.

Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73, was composed by Johannes Brahms in the summer of 1877, during a visit to Pörtschach am Wörthersee, a town in the Austrian province of Carinthia. Its composition was brief in comparison with the 21 years it took him to complete his First Symphony.

The Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68, is a symphony written by Johannes Brahms. Brahms spent at least fourteen years completing this work, whose sketches date from 1854. Brahms himself declared that the symphony, from sketches to finishing touches, took 21 years, from 1855 to 1876. The premiere of this symphony, conducted by the composer's friend Felix Otto Dessoff, occurred on 4 November 1876, in Karlsruhe, then in the Grand Duchy of Baden. A typical performance lasts between 45 and 50 minutes.

Franz Liszt composed his Piano Concerto No. 1 in E♭ major, S.124 over a 26-year period; the main themes date from 1830, while the final version is dated 1849. The concerto consists of four movements and lasts approximately 20 minutes. It premiered in Weimar on February 17, 1855, with Liszt at the piano and Hector Berlioz conducting.

Symphony No. 4, Op. 29, FS 76, also known as "The Inextinguishable", was completed by Danish composer Carl Nielsen in 1916. Composed against the backdrop of World War I, this symphony is among the most dramatic that Nielsen wrote, featuring a "battle" between two sets of timpani.

A Symphony to Dante's Divine Comedy, S.109, or simply the "Dante Symphony", is a choral symphony composed by Franz Liszt. Written in the high romantic style, it is based on Dante Alighieri's journey through Hell and Purgatory, as depicted in The Divine Comedy. It was premiered in Dresden on 7. November 1857, with Liszt conducting himself, and was unofficially dedicated to the composer's friend and future son-in-law Richard Wagner. The entire symphony takes approximately 50 minutes to perform.

The Symphony No. 5 in E-flat major, Op. 82, is a three-movement work for orchestra written from 1914 to 1915 by the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius. He revised it in 1916 and again from 1917 to 1919, at which point it reached its final form.

The Symphony No. 3 in C major, Op. 52, is a three-movement work for orchestra written from 1904 to 1907 by the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius.

The Symphony No. 2 in E minor and C major by Arnold Bax was completed in 1926, after he had worked on it for two years. It was dedicated to Serge Koussevitzky, who conducted the first two performances of the work on 13 and 14 December 1929.

The Symphony No. 6 by Arnold Bax was completed on February 10, 1935. The symphony is dedicated to Sir Adrian Boult. It is, according to David Parlett, "[Bax's] own favourite and widely regarded as his greatest ... powerful and tightly controlled". It was given its world premiere by the Royal Philharmonic on November 21 of the year of composition, 1935.

Ernest Chausson's Symphony in B-flat major, Op. 20, his only symphony, was written in 1890 and is often considered his masterpiece.

Robert Simpson composed his Seventh Symphony in 1977, the same year he completed his Sixth Symphony. Composition was begun 26 September and concluded 23 October in Chearsley. The work is dedicated to Hans Keller and his wife, Milein Keller, and was first performed by the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Brian Wright at the Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool on 30 October 1984. It is a one-movement work of approximately 28 minutes duration, and since its first performance it has become one of Simpson's most frequently heard symphonies.

Symphony No. 2, Ascensão (Ascension) is a composition by the Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos, written between 1917 and 1944.

The Symphony No. 2 in E minor is a symphony composed by Havergal Brian between 1930 and 1931. The work was inspired by Goethe's drama Götz von Berlichingen. Originally it did not bear any dedication, but in 1972 he retrospectively dedicated it to his then recently deceased daughter Elfreda Brian. While it appears to be a traditional, four-movement symphony in the German postromantic tradition, Brian greatly deviates from convention and his personal approach to the symphonic discourse only shares superficial elements with other composers.

References

- ↑ Mark Doran, "Robert Simpson: His Fifth Symphony at the Proms," The Musical Times131 1770 (1990): 422 - 423. "Andrew Davis conducts the work again in the Prom on 9 August."

- ↑ Andrew Jacksons, "Recordings and Reviews of Simpson's Works Archived 2008-10-11 at the Wayback Machine . Accessed 4 March 2008