Aaron Copland was an American composer, critic, writer, teacher, pianist, and conductor of his own and other American music. Copland was referred to by his peers and critics as the "Dean of American Composers". The open, slowly changing harmonies in much of his music are typical of what many consider the sound of American music, evoking the vast American landscape and pioneer spirit. He is best known for the works he wrote in the 1930s and 1940s in a deliberately accessible style often referred to as "populist" and which he called his "vernacular" style. Works in this vein include the ballets Appalachian Spring, Billy the Kid and Rodeo, his Fanfare for the Common Man and Third Symphony. In addition to his ballets and orchestral works, he produced music in many other genres, including chamber music, vocal works, opera, and film scores.

An octatonic scale is any eight-note musical scale. However, the term most often refers to the ancohemitonic symmetric scale composed of alternating whole and half steps, as shown at right. In classical theory, this symmetrical scale is commonly called the octatonic scale, although there are a total of 43 enharmonically inequivalent, transpositionally inequivalent eight-note sets.

Harold Samuel Shapero was an American composer.

Symphony No. 3 was Aaron Copland's final symphony. It was written between 1944 and 1946, and its first performance took place on October 18, 1946 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra performing under Serge Koussevitzky. If the early Dance Symphony is included in the count, it is actually Copland's fourth symphony.

Franz Schubert's Symphony No. 8 in B minor, D. 759, commonly known as the Unfinished Symphony, is a musical composition that Schubert started in 1822 but left with only two movements—though he lived for another six years. A scherzo, nearly completed in piano score but with only two pages orchestrated, also survives.

The Symphony of Psalms is a choral symphony in three movements composed by Igor Stravinsky in 1930 during his neoclassical period. The work was commissioned by Serge Koussevitzky to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The symphony derives its name from the use of Psalm texts in the choral parts.

The Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64 by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was composed between May and August 1888 and was first performed in Saint Petersburg at the Mariinsky Theatre on November 17 of that year with Tchaikovsky conducting. It is dedicated to Theodor Avé-Lallemant.

Connotations is a classical music composition for symphony orchestra written by American composer Aaron Copland. Commissioned by Leonard Bernstein in 1962 to commemorate the opening of Philharmonic Hall in New York City, United States, this piece marks a departure from Copland's populist period, which began with El Salón México in 1936 and includes the works he is most famous for such as Appalachian Spring, Lincoln Portrait and Rodeo. It represents a return to a more dissonant style of composition in which Copland wrote from the end of his studies with French pedagogue Nadia Boulanger and return from Europe in 1924 until the Great Depression. It was also Copland's first dodecaphonic work for orchestra, a style he had disparaged until he heard the music of French composer Pierre Boulez and adapted the method for himself in his Piano Quartet of 1950. While the composer had produced other orchestral works contemporary to Connotations, it was his first purely symphonic work since his Third Symphony, written in 1947.

Ralph Vaughan Williams composed his Symphony in E minor, published as Symphony No. 6, in 1944–47, during and immediately after World War II and revised in 1950. Dedicated to Michael Mullinar, it was first performed, in its original version, by Sir Adrian Boult and the BBC Symphony Orchestra on 21 April 1948. Within a year it had received some 100 performances, including the U.S. premiere by the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Serge Koussevitzky on 7 August 1948. Leopold Stokowski gave the first New York performances the following January with the New York Philharmonic and immediately recorded it, declaring that "this is music that will take its place with the greatest creations of the masters." However, Vaughan Williams, very nervous about this symphony, threatened several times to tear up the draft. At the same time, his programme note for the first performance took a defiantly flippant tone.

Aaron Copland's Clarinet Concerto was written between 1947 and 1949, although a first version was available in 1948. The concerto was later choreographed by Jerome Robbins for the ballet Pied Piper (1951).

The Symphony No. 3 in E♭ major, Op. 10, B. 34, is a classical composition by Antonín Dvořák.

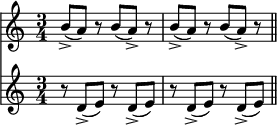

Harold Shapero completed the Symphony for Classical Orchestra in B-flat major on March 10, 1947, in Newton Centre, Massachusetts. It is written for an orchestra consisting of piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets in B-flat, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 2 horns in F, 2 trumpets in C, 2 tenor trombones and one bass, timpani and strings. Although labelled "Classical," many of the work's features point to Beethoven rather than Haydn or Mozart, such as "the way in which Shapero paces himself, alternating long passages in the tonic and the dominant, with fast, dramatic modulations often reserved for transitions and developments." Nicolas Slonimsky remarked on how the piece is "premeditatedly cast in the proclamatory key of B-flat major, the natural tonality of the bugle, and ending in a display of tonic major triads." But there are modern features as well, with "the work's orchestration, in general, ... distinctively bright and brassy, and undoubtedly derived a fair amount from Piston and Copland, as well as from the composer's experience as a dance band arranger."

The Symphony No. 6 by Walter Piston was completed in 1955.

Robert Moffat (variously "Moffatt" and "Moffett") Palmer was an American composer, pianist and educator. He composed more than 90 works, including two symphonies, Nabuchodonosor, a piano concerto, four string quartets, three piano sonatas and numerous works for chamber ensembles.

Schubert's Symphony in D major, D 708A, is an unfinished work that survives in an incomplete eleven-page sketch written for piano solo. It is one of Schubert's six unfinished symphonies. It was begun in 1820 or 1821, with initial sketches made for the opening sections of the first, second, and fourth movements, and an almost complete sketch for the third movement. He abandoned this symphony after this initial phase of work and never returned to it, although Schubert would live for another seven years. British conductor and composer Brian Newbould, an authority on Schubert's music, has speculated that the symphony was left incomplete due to problems Schubert faced in orchestrating the sketch.

Symphony No. 10, Sumé pater patrium: Sinfonia ameríndia com coros (Oratorio) is a composition by the Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos, written in 1952–53. The broadcast performance of the world-premiere performance under the composer's direction lasts just over 67 minutes.

The Concerto for Piano and Orchestra is a musical composition by the American composer Aaron Copland. The work was commissioned by the conductor Serge Koussevitzky who was then music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. It was first performed on January 28, 1927, by the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Koussevitzky with the composer himself as the soloist. The piece is dedicated to Copland's patron Alma Morgenthau Wertheim.

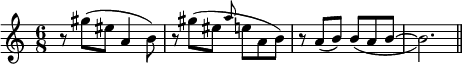

The Short Symphony, or Symphony No. 2, is a symphony written by the American composer Aaron Copland from 1931 to 1933. The name derives from the symphony's short length of only 15 minutes. The work is dedicated to Copland's friend, the Mexican composer and conductor Carlos Chávez. The symphony's first movement is in sonata-allegro form, and its slow second movement follows an adapted ternary form. The third movement resembles the sonata-allegro but has indications of cyclic form. The composition contains complex rhythms and polyharmonies, and it incorporates the composer's emerging interest in serialism as well as influences from Mexican music and German cinema. The symphony includes scoring for a heckelphone and a piano while omitting trombones and a percussion section. Copland later arranged the symphony as a sextet.

Felix Weingartner's Symphony No. 2 in E-flat major, Op. 29 is a musical composition that Weingartner started in 1897 and completed in 1899. The overall musical language of the piece is late-romantic although with a high emphasis on Schubertian melodicism. Furthermore, as with other contemporary Austrian composers of the end of the 20th century such as Gustav Mahler or Hans Rott, his second symphony heavily uses a Brucknerian treatment of simple motifs through extensive repetition and grand orchestration.