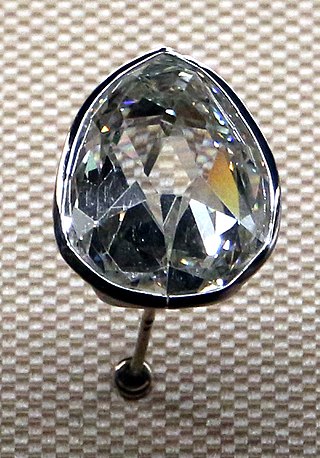

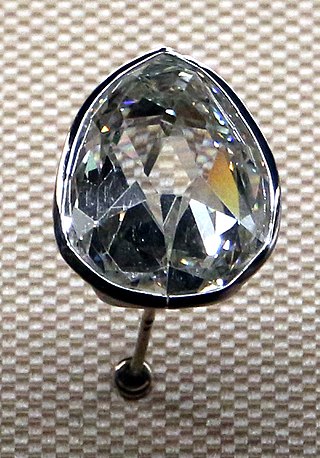

The Hope Diamond is a 45.52 carats diamond that has been famed for its great size since the 18th century. Extracted in the 17th century from the Kollur Mine in Guntur, India, the Hope Diamond is a blue diamond. Its exceptional size has revealed new information about the formation of diamonds.

The Peacock Throne was the imperial throne of Hindustan. The throne is named after the dancing peacocks at its rear and was the seat of the Mughal emperors of India from 1635 to 1739. It was commissioned in the early 17th century by Emperor Shah Jahan and was located in the Diwan-i-Khas in the Red Fort of Delhi. The original throne was taken as a war trophy by Nader Shah, Shah of Iran in 1739 after his invasion of India. Its replacement disappeared during or soon after the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605–1689) was a 17th-century French gem merchant and traveler. Tavernier, a private individual and merchant traveling at his own expense, covered, by his own account, 60,000 leagues in making six voyages to Persia and India between the years 1630 and 1668. In 1675, Tavernier, at the behest of his patron Louis XIV, known as the Sun King, published Les Six Voyages de Jean-Baptiste Tavernier.

The Sancy, a pale yellow diamond of 55.23 carats (11.046 g), was once reputed to have belonged to the Mughals of antiquity, but it is more likely of Indian origin owing to its cut, which is unusual by Western standards. The stone has been owned by a number of important figures in European history, such as Charles the Bold, James VI and I, and the Astor family.

The Orlov, also often considered to be the same diamond known as The Great Mughal Diamond, is a large diamond of Indian origin, currently displayed as a part of the Diamond Fund collection of Moscow's Kremlin Armoury. It is described as having the shape and proportions of half a chicken's egg. In 1774, it was encrusted into the Imperial Sceptre of Russian Empress Catherine the Great.

The French Crown Jewels and Regalia comprise the crowns, orb, sceptres, diadems and jewels that were symbols of Royal or Imperial power between 752 and 1870. These were worn by many Kings and Queens of France as well as Emperor Napoleon. The set was finally broken up, with most of it sold off in 1885 by the Third Republic. The surviving French Crown Jewels, principally a set of historic crowns, diadems and parures, are mainly on display in the Galerie d'Apollon of the Louvre, France's premier museum and former royal palace, together with the Regent Diamond, the Sancy Diamond and the 105-carat (21.0 g) Côte-de-Bretagne red spinel, carved into the form of a dragon. In addition, some gemstones and jewels are on display in the Treasury vault of the Mineralogy gallery in the National Museum of Natural History.

Kollur Mine was a series of gravel-clay pits on the south bank of the Krishna River in the state of Andhra Pradesh, India. It is thought to have produced many large diamonds, known as Golconda diamonds, several of which are or have been a part of crown jewels.

The Great Chrysanthemum Diamond is a famous diamond measuring 104.15 carats with a pear-shaped modified brilliant cut, rated in colour as Fancy Orange-Brown and I1 clarity by the Gemological Institute of America. The Great Chrysanthemum is roughly the same size as the re-cut Kohinoor and almost three times the size of the Hope Diamond, The Great Chrysanthemum has the dimensions of 39.10 x 24.98 x 16.00 mm. and features 67 facets on the crown, 57 facets on the pavilion and 65 vertical facets along the girdle. The diamond, designed as a pendant, became the central focus of a necklace with 410 oval, pear-shaped, round and marquis diamonds.

Harry Winston was an American jeweler. He donated the Hope Diamond to the Smithsonian Institution in 1958 after owning it for a decade. He also traded the Portuguese Diamond to the Smithsonian in 1963 in exchange for 3,800 carats of small diamonds.

The Ruspoli Sapphire, also known as the Wooden Spoon Seller's Sapphire, is a 136.9 carat blue sapphire that has historically been confused with Grand Sapphire of Louis XIV. Recent research has shown that not only are these two separate gems, but also that the story of once being owned by the Ruspoli family and having been acquired from a wooden spoon seller in Bengal are both apocryphal tales with no basis. The origins of this confusion stem from a book published in 1858 by Charles Barbot, who confused the Ruspoli Sapphire with the Grand Sapphire of Louis XIV.

The Florentine Diamond is a lost diamond of Indian origin. It is light yellow in colour with very slight green overtones. It is cut in the form of an irregular nine-sided 126-facet double rose cut, with a weight of 137.27 carats. The stone is also known as the Tuscan, the Tuscany Diamond, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, the Austrian Diamond, Austrian Yellow Diamond, and the Dufner Diamond.

The Shah Diamond was found at the Golconda mines in what is now Telangana, South India, probably in 1450, and it is currently held in the Diamond Fund collection of Moscow's Kremlin Armoury.

The largest flawless diamond in the world is known as The Paragon, a D-color gem weighing 137.82 carats (27.564 g), and the tenth largest white diamond in the world. The gem was mined in Brazil and attracted attention for being an exceptional white, flawless stone of great size. The Mayfair-based jeweller Graff Diamonds acquired the stone in Antwerp, cut it into an unusual seven-sided kite shield configuration, and set it in a necklace which separates to both necklace and bracelet lengths. Apart from the main stone, this necklace also contains rare pink, blue, and yellow diamonds, making a total mass of 190.27 carats (38.054 g). The necklace has associations with the end of the millennium and was worn by model Naomi Campbell at a diamond gala held by De Beers and Versace at Syon House in 1999.

The Maharaja of Indore Necklace is a diamond and emerald-studded necklace. As of 2008, it is on display at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., United States. It was originally named the Spanish Inquisition Necklace by the American jeweller Harry Winston, though it had no known connection with the historical Spanish Inquisition. The name was changed in 2021 by the Smithsonian Institution to reflect its actual provenance, having been first owned by Tukoji Rao III, Maharaja of Indore in the early 20th century.

The Wittelsbach-Graff Diamond is a 31.06-carat (6.212 g) deep-blue diamond with internally flawless clarity, originating in the Kollur Mine, India. Laurence Graff purchased the Wittelsbach Diamond in 2008 for £16.4 million. In 2010, Graff revealed he had had the diamond cut by three diamond cutters to remove flaws. The diamond was now more than 4 carats (800 mg) lighter and was renamed the Wittelsbach-Graff Diamond. There is controversy, as critics claim the recutting has so altered the diamond as to make it unrecognisable, compromising its historical integrity.

John Francillon (1744–1816) was a jeweler and lapidary, an English naturalist and an entomologist of Huguenot descent.

The Hooker Emerald Brooch is an emerald brooch designed by Tiffany & Co. The brooch is on display in the Janet Annenberg Hooker Hall of Geology, Gems, and Minerals at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C., United States.

The Great Table was a large pink diamond that had been studded in the throne of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan. It has been described in the book of the French jeweller Jean-Baptiste Tavernier in 1642, who gave it its name.

Golconda diamonds are mined in the Godavari-Krishna delta region of Andhra Pradesh, India. Golconda Fort in the western part of modern-day Hyderabad was a seat of the Golconda Sultanate and became an important centre for diamond enhancement, lapidary, and trading. Golconda diamonds are graded as Type IIa, are formed of pure carbon, are devoid of nitrogen, and are large with high clarity. They are often described as diamonds of the first water, making them among history's most-celebrated diamonds. The phrase "Golconda diamond" became synonymous with diamonds of incomparable quality.

Blue diamond is a type of diamond which exhibits all of the same inherent properties of the mineral except with the additional element of blue color in the stone. They are colored blue by trace impurities of boron within the crystalline lattice structure. Blue diamonds belong to a subcategory of diamonds called fancy color diamonds, the generic name for diamonds that exhibit intense color.