Evolutionary developmental biology is a field of biological research that compares the developmental processes of different organisms to infer how developmental processes evolved.

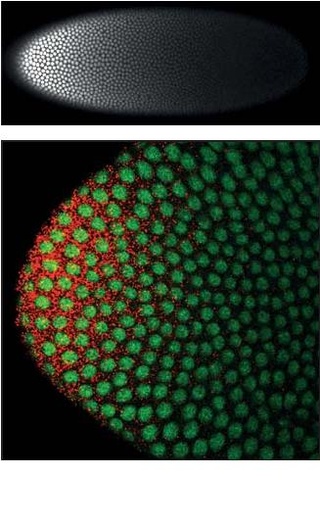

The blastocyst is a structure formed in the early embryonic development of mammals. It possesses an inner cell mass (ICM) also known as the embryoblast which subsequently forms the embryo, and an outer layer of trophoblast cells called the trophectoderm. This layer surrounds the inner cell mass and a fluid-filled cavity or lumen known as the blastocoel. In the late blastocyst, the trophectoderm is known as the trophoblast. The trophoblast gives rise to the chorion and amnion, the two fetal membranes that surround the embryo. The placenta derives from the embryonic chorion and the underlying uterine tissue of the mother. The corresponding structure in non-mammalian animals is an undifferentiated ball of cells called the blastula.

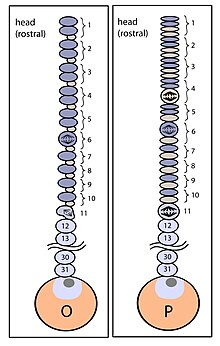

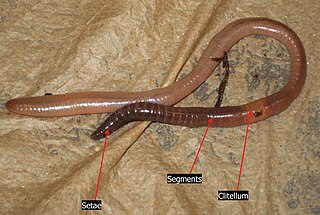

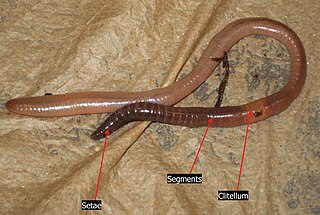

Segmentation in biology is the division of some animal and plant body plans into a linear series of repetitive segments that may or may not be interconnected to each other. This article focuses on the segmentation of animal body plans, specifically using the examples of the taxa Arthropoda, Chordata, and Annelida. These three groups form segments by using a "growth zone" to direct and define the segments. While all three have a generally segmented body plan and use a growth zone, they use different mechanisms for generating this patterning. Even within these groups, different organisms have different mechanisms for segmenting the body. Segmentation of the body plan is important for allowing free movement and development of certain body parts. It also allows for regeneration in specific individuals.

The somites are a set of bilaterally paired blocks of paraxial mesoderm that form in the embryonic stage of somitogenesis, along the head-to-tail axis in segmented animals. In vertebrates, somites subdivide into the dermatomes, myotomes, sclerotomes and syndetomes that give rise to the vertebrae of the vertebral column, rib cage, part of the occipital bone, skeletal muscle, cartilage, tendons, and skin.

Somitogenesis is the process by which somites form. Somites are bilaterally paired blocks of paraxial mesoderm that form along the anterior-posterior axis of the developing embryo in segmented animals. In vertebrates, somites give rise to skeletal muscle, cartilage, tendons, endothelium, and dermis.

The clitellum is a thickened glandular and non-segmented section of the body wall near the head in earthworms and leeches that secretes a viscid sac in which eggs are stored. It is located near the anterior end of the body, between the fourteenth and seventeenth segments. The number of the segments to where the clitellum begins and the number of segments that make up the clitellum are important for identifying earthworms. In microdrile earthworms, the clitellum has only one layer, resulting in a smaller quantity of eggs than that of the megadrile earthworms, which have larger multi-layered clitellum that have special cells that secrete albumin into the worms' egg sac.

In embryology, cleavage is the division of cells in the early development of the embryo, following fertilization. The zygotes of many species undergo rapid cell cycles with no significant overall growth, producing a cluster of cells the same size as the original zygote. The different cells derived from cleavage are called blastomeres and form a compact mass called the morula. Cleavage ends with the formation of the blastula, or of the blastocyst in mammals.

The neural crest is a ridge-like structure that is formed transiently between the epidermal ectoderm and neural plate during vertebrate development. Neural crest cells originate from this structure through the epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and in turn give rise to a diverse cell lineage—including melanocytes, craniofacial cartilage and bone, smooth muscle, dentin, peripheral and enteric neurons, adrenal medulla and glia.

The Clitellata are a class of annelid worms, characterized by having a clitellum – the 'collar' that forms a reproductive cocoon during part of their life cycles. The clitellates comprise around 8,000 species. Unlike the class of Polychaeta, they do not have parapodia and their heads are less developed.

Paraxial mesoderm, also known as presomitic or somitic mesoderm, is the area of mesoderm in the neurulating embryo that flanks and forms simultaneously with the neural tube. The cells of this region give rise to somites, blocks of tissue running along both sides of the neural tube, which form muscle and the tissues of the back, including connective tissue and the dermis.

An asymmetric cell division produces two daughter cells with different cellular fates. This is in contrast to symmetric cell divisions which give rise to daughter cells of equivalent fates. Notably, stem cells divide asymmetrically to give rise to two distinct daughter cells: one copy of the original stem cell as well as a second daughter programmed to differentiate into a non-stem cell fate.

An equivalence group is a set of unspecified cells that have the same developmental potential or ability to adopt various fates. Our current understanding suggests that equivalence groups are limited to cells of the same ancestry, also known as sibling cells. Often, cells of an equivalence group adopt different fates from one another.

Within the field of developmental biology, one goal is to understand how a particular cell develops into a final cell type, known as fate determination. Within an embryo, several processes play out at the cellular and tissue level to create an organism. These processes include cell proliferation, differentiation, cellular movement and programmed cell death. Each cell in an embryo receives molecular signals from neighboring cells in the form of proteins, RNAs and even surface interactions. Almost all animals undergo a similar sequence of events during very early development, a conserved process known as embryogenesis. During embryogenesis, cells exist in three germ layers, and undergo gastrulation. While embryogenesis has been studied for more than a century, it was only recently that scientists discovered that a basic set of the same proteins and mRNAs are involved in embryogenesis. Evolutionary conservation is one of the reasons that model systems such as the fly, the mouse, and other organisms are used as models to study embryogenesis and developmental biology. Studying model organisms provides information relevant to other animals, including humans. While studying the different model systems, cells fate was discovered to be determined via multiple ways, two of which are by the combination of transcription factors the cells have and by the cell-cell interaction. Cells' fate determination mechanisms were categorized into three different types, autonomously specified cells, conditionally specified cells, or syncytial specified cells. Furthermore, the cells' fate was determined mainly using two types of experiments, cell ablation and transplantation. The results obtained from these experiments, helped in identifying the fate of the examined cells.

Vasa is an RNA binding protein with an ATP-dependent RNA helicase that is a member of the DEAD box family of proteins. The vasa gene is essential for germ cell development and was first identified in Drosophila melanogaster, but has since been found to be conserved in a variety of vertebrates and invertebrates including humans. The Vasa protein is found primarily in germ cells in embryos and adults, where it is involved in germ cell determination and function, as well as in multipotent stem cells, where its exact function is unknown.

Capitella teleta is a small, cosmopolitan, segmented annelid worm. It is a well-studied invertebrate, which has been cultured for use in laboratories for over 30 years. C. teleta is the first marine polychaete to have its genome sequenced.

Helobdella robusta is a leech of the family Glossiphoniidae. Its genome has been sequenced by the Joint Genome Institute, and its early development has been studied extensively. Helobdella leeches called "H. robusta" in literature may not all be from the same species, though they are closely related. At least two species originally termed H. robusta are present at the same locality, the Sacramento River at the Sacramento Fairgrounds. Another closely related leech is now called Helobdella sp. (Austin).

Myogenic factor 5 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the MYF5 gene. It is a protein with a key role in regulating muscle differentiation or myogenesis, specifically the development of skeletal muscle. Myf5 belongs to a family of proteins known as myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs). These basic helix loop helix transcription factors act sequentially in myogenic differentiation. MRF family members include Myf5, MyoD (Myf3), myogenin, and MRF4 (Myf6). This transcription factor is the earliest of all MRFs to be expressed in the embryo, where it is only markedly expressed for a few days. It functions during that time to commit myogenic precursor cells to become skeletal muscle. In fact, its expression in proliferating myoblasts has led to its classification as a determination factor. Furthermore, Myf5 is a master regulator of muscle development, possessing the ability to induce a muscle phenotype upon its forced expression in fibroblastic cells.

Segmentation is the physical characteristic by which the human body is divided into repeating subunits called segments arranged along a longitudinal axis. In humans, the segmentation characteristic observed in the nervous system is of biological and evolutionary significance. Segmentation is a crucial developmental process involved in the patterning and segregation of groups of cells with different features, generating regional properties for such cell groups and organizing them both within the tissues as well as along the embryonic axis.

Homeotic protein bicoid is encoded by the bcd maternal effect gene in Drosophilia. Homeotic protein bicoid concentration gradient patterns the anterior-posterior (A-P) axis during Drosophila embryogenesis. Bicoid was the first protein demonstrated to act as a morphogen. Although bicoid is important for the development of Drosophila and other higher dipterans, it is absent from most other insects, where its role is accomplished by other genes.

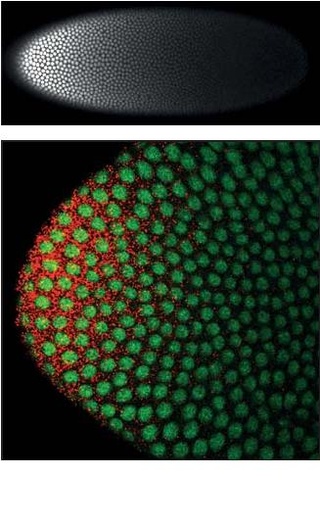

Leech embryogenesis is the process by which the embryo of the leech forms and develops. The embryonic development of the larva occurs as a series of stages. During stage 1, the first cleavage occurs, which gives rise to an AB and a CD blastomere, and is in the interphase of this cell division when a yolk-free cytoplasm called teloplasm is formed. The teloplasm is known to be a determinant for the specification of the D cell fate. In stage 3, during the second cleavage, an unequal division occurs in the CD blastomere. As a consequence, it creates a large D cell on the left and a smaller C cell to the right. This unequal division process is dependent on actomyosin, and by the end of stage 3 the AB cell divides. On stage 4 of development, the micromeres and teloblast stem cells are formed and subsequently, the D quadrant divides to form the DM and the DNOPQ teloblast precursor cells. By the end stage 6, the zygote contains a set of 25 micromeres, 3 macromeres and 10 teloblasts derived from the D quadrant.