Related Research Articles

Waiting for Godot is a play by Irish playwright Samuel Beckett in which two characters, Vladimir (Didi) and Estragon (Gogo), engage in a variety of discussions and encounters while awaiting the titular Godot, who never arrives. Waiting for Godot is Beckett's reworking of his own original French-language play, En attendant Godot, and is subtitled "a tragicomedy in two acts". In a poll conducted by the British Royal National Theatre in 1998/99, it was voted as the "most significant English-language play of the 20th century".

Peter Seamus O'Toole was an English actor. Known for his leading roles on stage and screen, he received several accolades including the Academy Honorary Award, a BAFTA Award, a Primetime Emmy Award, and four Golden Globe Awards as well as nominations for a Grammy Award and a Laurence Olivier Award.

Gao Xingjian is a Chinese émigré and later French naturalized novelist, playwright, critic, painter, photographer, film director, and translator who in 2000 was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature "for an oeuvre of universal validity, bitter insights and linguistic ingenuity." He is also a noted translator, screenwriter, stage director, and a celebrated painter.

Experimental theatre, inspired largely by Wagner's concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, began in Western theatre in the late 19th century with Alfred Jarry and his Ubu plays as a rejection of both the age in particular and, in general, the dominant ways of writing and producing plays. The term has shifted over time as the mainstream theatre world has adopted many forms that were once considered radical.

Roger Rees was a Welsh actor and director. He won an Olivier Award and a Tony Award for his performance as the lead in The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. He also received Obie Awards for his role in The End of the Day and as co-director of Peter and the Starcatcher. Rees was posthumously inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame in November 2015.

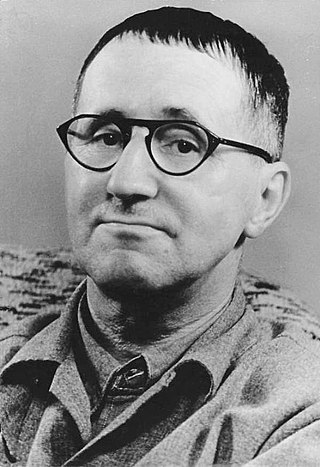

The distancing effect, also translated as alienation effect, is a concept in performing arts credited to German playwright Bertolt Brecht.

Theatre of China has a long and complex history. Traditional Chinese theatre, generally in the form of Chinese opera, is musical in nature. Chinese theatre can trace its origin back a few millennia to ancient China, but the Chinese opera started to develop in the 12th century. Western forms like the spoken drama, western-style opera, and ballet did not arrive in China until the 20th century.

Twentieth-century theatre describes a period of great change within the theatrical culture of the 20th century, mainly in Europe and North America. There was a widespread challenge to long-established rules surrounding theatrical representation; resulting in the development of many new forms of theatre, including modernism, expressionism, impressionism, political theatre and other forms of Experimental theatre, as well as the continuing development of already established theatrical forms like naturalism and realism.

Alan Stanford is an English-Irish actor, director and writer. He has worked in the theatre for many years, including a 30 year association with the Gate Theatre as both actor and director. He is well known for playing George Manning in the popular Irish drama series Glenroe.

The Lehrstücke are a radical and experimental form of modernist theatre developed by Bertolt Brecht and his collaborators from the 1920s to the late 1930s. The Lehrstücke stem from Brecht's epic theatre techniques but as a core principle explore the possibilities of learning through acting, playing roles, adopting postures and attitudes etc. and hence no longer divide between actors and audience. Brecht himself translated the term as learning-play, emphasizing the aspect of learning through participation, whereas the German term could be understood as teaching-play. Reiner Steinweg goes so far as to suggest adopting a term coined by the Brazilian avant garde theatre director Zé Celso, Theatre of Discovery, as being even clearer.

A Fabel is a critical analysis of the plot of a play. It is a dramaturgical technique that was pioneered by Bertolt Brecht, a 20th century German theatre practitioner.

Conceptualised by 20th century German director and theatre practitioner Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956), "The Modern Theatre Is the Epic Theatre" is a theoretical framework implemented by Brecht in the 1930s, which challenged and stretched dramaturgical norms in a postmodern style. This framework, written as a set of notes to accompany Brecht's satirical opera, ‘Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny’, explores the notion of "refunctioning" and the concept of the Separation of the Elements. This framework was most proficiently characterised by Brecht's nihilistic anti-bourgeois attitudes that “mirrored the profound societal and political turmoil of the Nazi uprising and post WW1 struggles”. Brecht's presentation of this theatrical structure adopts a style that is austere, utilitarian and remains instructional rather than systematically categorising itself as a form that is built towards a more entertaining and aesthetic lens. ‘The Modern Theatre Is the Epic Theatre’ incorporates early formulations of Brechtian conventions and techniques such as Gestus and the V-Effect. It employs an episodic arrangement rather than a traditional linear composition and encourages an audience to see the world as it is regardless of the context. The purpose of this new avant-garde outlook on theatrical performance aimed to “exhort the viewer to greater political vigilance, bringing the Marxist objective of a classless utopia closer to realisation”.

The Good Person of Szechwan is a play written by the German dramatist Bertolt Brecht, in collaboration with Margarete Steffin and Ruth Berlau. The play was begun in 1938 but not completed until 1941, while the author was in exile in the United States. It was first performed in 1943 at the Zürich Schauspielhaus in Switzerland, with a musical score and songs by Swiss composer Huldreich Georg Früh. Today, Paul Dessau's composition of the songs from 1947 to 1948, also authorized by Brecht, is the better-known version. The play is an example of Brecht's "non-Aristotelian drama", a dramatic form intended to be staged with the methods of epic theatre. The play is a parable set in the Chinese "city of Sichuan".

Gábor Tompa is an internationally renowned Romanian theater and film director, poet, essayist and teacher. Between 2007 and 2016 he was the Head of Directing at the Theatre and Dance Department of the University of California, San Diego. He is the general and artistic director of the Hungarian Theatre of Cluj since 1990, the theatre is member of the Union of the Theatres of Europe (UTE) since 2008. Founder and artistic director of the Interferences International Theatre Festival in Cluj, Romania. President of the Union of the Theatres of Europe since 2018.

The Other Shore is a play by the Chinese writer Gao Xingjian. It was first published into English in 1997 and translated again in 1999.

The Actor's Workshop was a theatre company founded in San Francisco in 1952. It was the first professional theatre on the west coast to premiere many of the modern American classics such as Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman and The Crucible, and the world dramas of Samuel Beckett, Bertolt Brecht, Jean Genet and Harold Pinter. For the 1953–1954 season, the Workshop offered six plays: Lysistrata, by Aristophanes; Venus Observed, by Christopher Fry; Death of a Salesman, by Arthur Miller; a revival of Playboy; The Cherry Orchard, by Anton Chekhov; and Tonight at 8.30, by Noël Coward. On April 15, 1955, the Actor's Workshop signed the first Off-Broadway Equity contract to be awarded outside New York City.

Peter O'Shaughnessy OAM was an Australian actor, theatre director, producer and writer who presented the work of playwrights ranging from Shakespeare, Shaw, Ibsen, Strindberg, Chekhov to modern dramatists, such as Ionesco, Pinter and Beckett. He acted as a mentor to and collaborator with comedian Barry Humphries in his early career. He attended Xavier College, Melbourne.

Minoru Betsuyaku was one of Japan's most prominent postwar playwrights, novelists, and essayists, associated with the Angura ("underground") theater movement in Japan. He won a name for himself as a writer in the "nonsense" genre and helped lay the foundations of the Japanese "theater of the absurd." His works focused on the aftermath of the war and especially the nuclear holocaust.

Amir Reza Koohestani is an Iranian theatre maker who was born in Shiraz, Iran.

The Firehouse Theater of Minneapolis and later of San Francisco was a significant producer of experimental, theater of the absurd, and avant guard theater in the 1960s and 1970s. Its productions included new plays and world premieres, often presented with radical or inventive directorial styles. The Firehouse introduced playwrights and new plays to Minneapolis and San Francisco. It premiered plays by Megan Terry, Sam Shepard, Jean-Claude van Itallie, María Irene Fornés and others; and it presented plays by Harold Pinter, John Arden, August Strindberg, John Osborne, Arthur Kopit, Eugène Ionesco, Berthold Brecht, Samuel Beckett and others. In a 1987 interview Martha Boesing, the artistic director of another Minneapolis theatre, described the Firehouse Theater as "the most extreme of all the groups creating experimental theater in the sixties, and the closest to Artaud’s vision." Writing in 1968, The New York Times said that the Firehouse Theater "has been doing avantgarde plays in Minneapolis nearly as long as the Tyrone Guthrie Theater has been doing the other kind, and with much less help from the Establishment." That same year, when a federal grant was provided to support the Firehouse, it was pointed out in the Congressional Record that the Firehouse Theatre "is the only major theatre dealing experimentally with the writing of plays and their production outside the metropolitan New York area."

References

- ↑ Sen, Ma (1991). "The Theater of the Absurd in Mainland China: Kao Hsing-chien's The Bus Stop". Post-Mao Sociopolitical Changes in Mainland China: The Literary Perspective (38). Taipei: Institute of International Relations: 144.

- 1 2 3 4 Xingjian, Gao (1985). Bus Stop.

- 1 2 "Bus Stop". Encyclopedia of Contemporary Chinese Culture. Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- 1 2 Kirkwood, Carla (2008). "Occidentalism and Orientalism: Critically Framing Gao Xingjian's "Che Zhan" ("Bus Stop")". Diss. University of California, San Diego. Ann Arbor.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Conceison, Claire (2002). "Fleshing Out the Dramaturgy of Gao Xingjian". MCLC Resource Center. The Ohio State University. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- 1 2 Saltz, Rachel (9 April 2009). "At the Way Station of Life, Departing to Anywhere". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- 1 2 Barme, Geremie (July 1983). "Chinese Drama: To be or Not". The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs (10). The University of Chicago Press: 139–145. doi:10.2307/2158755. JSTOR 2158755.

- ↑ Beckett, Samuel (1954). Waiting For Godot . New York: Grove Press, Inc.

- ↑ Lackner, Michael; Chardonnes, Nikola (2014). Polyphony Embodied - Freedom and Fate in Gao Xingjian's Writings (1 ed.). Munich: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

- ↑ Chen, Xiaomei (2001). "A Stage in Search of a Tradition: The Dynamics of Form and Content in Post-Maoist Theatre". Asian Theatre Journal. 18 (2): 200. doi:10.1353/atj.2001.0014.

- ↑ Lackner, Michael; Chardonnes, Nikola (2014). Polyphony Embodied - Freedom and Fate in Gao Xingjian's Writings (1 ed.). Munich: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.