Ignaz Seipel was an Austrian Catholic priest and conservative politician, who served as the Chancellor of the First Austrian Republic twice during the 1920s and leader of the Christian Social Party. He is considered the most prominent statesman of the Austrian right in the interwar period.

Moses Joseph Roth was an Austrian-Jewish journalist and novelist, best known for his family saga Radetzky March (1932), about the decline and fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, his novel of Jewish life Job (1930) and his seminal essay "Juden auf Wanderschaft", a fragmented account of the Jewish migrations from eastern to western Europe in the aftermath of World War I and the Russian Revolution. In the 21st century, publications in English of Radetzky March and of collections of his journalism from Berlin and Paris created a revival of interest in Roth.

Hans Moser was an Austrian actor who, during his long career, from the 1920s up to his death, mainly played in comedy films. He was particularly associated with the genre of the Wiener Film. Moser appeared in over 150 films.

The history of the Jews in Austria probably begins with the exodus of Jews from Judea under Roman occupation. There have been Jews in Austria since the 3rd century CE. Over the course of many centuries, the political status of the community rose and fell many times: during certain periods, the Jewish community prospered and enjoyed political equality, and during other periods it suffered pogroms, deportations to concentration camps and mass murder, and antisemitism. The Holocaust drastically reduced the Jewish community in Austria and only 8,140 Jews remained in Austria according to the 2001 census. Today, Austria has a Jewish population of 10,300 which extends to 33,000 if Law of Return is accounted for, meaning having at least one Jewish grandparent.

Otto Rothstock was an Austrian Nazi living in Germany, who assassinated Austrian Jewish writer Hugo Bettauer.

Ida Jenbach was an Austrian playwright and screenwriter for German and Austrian cinema during the 1920s. She was one of the authors of the spirited farce Opera Ball that appeared at the Little Carnegie Playhouse in New York City in 1931. New York Times critic Mordaunt Hall praised this comedy as “cleverly acted by the principals.” The Opera Ball (Opernredoute) was a German film that had “captions in English lettered on the scenes to keep those unfamiliar with German au courant of what is happening.”

Cinema of Austria refers to the film industry based in Austria. Austria has had an active cinema industry since the early 20th century when it was the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and that has continued to the present day. Producer Sascha Kolowrat-Krakowsky, producer-director-writer Luise Kolm and the Austro-Hungarian directors Michael Curtiz and Alexander Korda were among the pioneers of early Austrian cinema. Several Austrian directors pursued careers in Weimar Germany and later in the United States, among them Fritz Lang, G. W. Pabst, Josef von Sternberg, Billy Wilder, Fred Zinnemann, and Otto Preminger.

Hans Karl Breslauer, born Johann Karl Breslauer, later often known as H. K. Breslauer, was an early Austrian film director, also an actor, screenwriter and author.

Willi Forst, born Wilhelm Anton Frohs was an Austrian actor, screenwriter, film director, film producer and singer. As a debonair actor he was a darling of the German-speaking film audiences, as a director, one of the most significant makers of the Viennese period musical melodramas and comedies of the 1930s known as Wiener Filme. From the mid-1930s he also recorded many records, largely of sentimental Viennese songs, for the Odeon Records label owned by Carl Lindström AG.

Sodom und Gomorrha: Die Legende von Sünde und Strafe is an Austrian silent epic film from 1922. It was shot on the Laaer Berg, Vienna, as the enormous backdrops specially designed and constructed for the film were too big for the Sievering Studios of the production company, Sascha-Film, in Sievering. The film is distinguished, not so much by the strands of its often opaque plot, as by its status as the largest and most expensive film production in Austrian film history. In the creation of the film between 3,000 and 14,000 performers, extras and crew were employed.

Julius von Borsody was an Austrian film architect and one of the most employed set designers in the Austrian and German cinemas of the late silent and early sound film periods. His younger brother, Eduard von Borsody, was a film director in Austria and Germany. He is also the great-uncle of German actress Suzanne von Borsody.

Joyless Street, also titled The Street of Sorrow or The Joyless Street, is a 1925 German silent film directed by Georg Wilhelm Pabst starring Greta Garbo, Asta Nielsen and Werner Krauss. It is based on a novel by Hugo Bettauer and widely considered an expression of New Objectivity in film.

Emil-Edwin Reinert, or Emile-Edwin Reinert, was a French film director, screenwriter, audio engineer and producer.

Maximilian Hugo Bettauer was a prolific Austrian writer and journalist, who was murdered by a Nazi Party follower on account of his opposition to antisemitism. He was well known in his lifetime; many of his books were bestsellers and in the 1920s a number were made into films, most notably Die freudlose Gasse, which dealt with prostitution, and Die Stadt ohne Juden, a satire against antisemitism.

The history of the Jews in Vienna, Austria, goes back over eight hundred years. There is evidence of a Jewish presence in Vienna from the 12th century onwards.

Johann Schwarzer was an Austrian photographer and pioneer producer of adult films through his Saturn-Film company.

Die zärtlichen Verwandten is a 1930 German comedy film directed by Richard Oswald and starring Harald Paulsen, Charlotte Ander, and Felix Bressart. The film's art direction was overseen by Franz Schroedter.

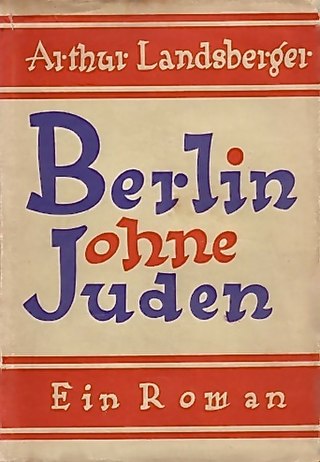

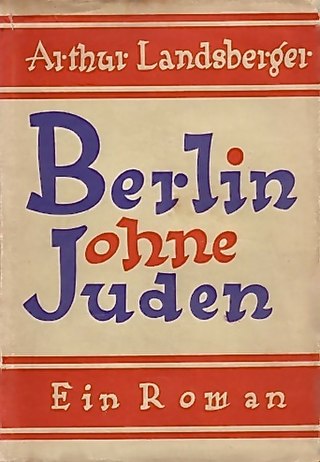

Berlin Without Jews is a 1925 dystopian novel by Arthur Landsberger. It is written from the point-of-view of two German families friendly to each other; the Oppenheims are Jewish, and the Rudenbergs are Lutherans. In the events of the book, a right-wing nationalist political party takes power and expels German Jews. The other factions of German politics and society stand by, doing nothing, thinking the Jews matter little. The expulsion has unfortunate consequences for Germany. German life is poorer both culturally and economically without the Jews, and the novel ends with the government sheepishly inviting the German Jews back and welcoming them as valued members of society.

The City Without Jews is a 1922 novel by Hugo Bettauer.

Robert Streibel is an Austrian historian, writer and poet.