The hedgehog and the snake, alternatively titled The snakes and the porcupine, was a fable originated by Laurentius Abstemius in 1490. From the following century it was accepted as one of Aesop's Fables in several European collections.

The hedgehog and the snake, alternatively titled The snakes and the porcupine, was a fable originated by Laurentius Abstemius in 1490. From the following century it was accepted as one of Aesop's Fables in several European collections.

The Venetian librarian Laurentius Abstemius created a Latin fable concerning a hedgehog and a viper in his Hecatomythium of 1490. In this the hedgehog begs shelter for the winter in the snake's hole. When the host suffers from its guest's prickles and asks it to leave, the hedgehog refuses, suggesting that it is for the one who is discontented with the lodging to leave it. [1]

In the following century variations of the fable appeared in several European collections and became sufficiently well known for Sir Philip Sydney to allude to it in his An Apology for Poetry . [2] By the 17th century it was being used as an example of ingratitude in moralistic works such as Christoph Murer's emblem book XL Emblemata [3] and the oil painting on copper by Jan van Kessel the Elder. [4] Another of these was included in the water features in the labyrinth of Versailles, set up by Louis XIV for the instruction of his son. [5] For this the king had been advised by the fabulist Charles Perrault, who records the fable in his work, [6] but the statues were associated at Versaille with the quatrains composed for them by Isaac de Benserade, who refers to the villain of the piece as a porcupine:

In England the fable appeared in several influential collections of Aesop's fables. Samuel Croxall's version features a porcupine and snakes and is applied in his long reflection to the injudicious choice either of friend or marriage partner. [8] Samuel Richardson's version is told of a snake and a hedgehog, with the advice that "It is not safe to join interest with strangers upon such terms as to lay ourselves at their mercy". [9]

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and storyteller who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. Of varied and unclear origins, the stories associated with his name have descended to modern times through a number of sources and continue to be reinterpreted in different verbal registers and in popular as well as artistic media.

The Monkey and the Cat is best known as a fable adapted by Jean de La Fontaine under the title Le Singe et le Chat that appeared in the second collection of his Fables in 1679 (IX.17). It is the source of popular idioms in both English and French, with the general meaning of being the dupe of another.

The Frogs Who Desired a King is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 44 in the Perry Index. Throughout its history, the story has been given a political application.

Laurentius Abstemius, born Lorenzo Bevilaqua, was an Italian writer and professor of philology, born at Macerata Feltria; his learned name Abstemius, literally "abstemious", plays on his family name of Bevilaqua ("drinkwater"). A Neo-Latin writer of considerable talents at the time of the Humanist revival of letters, his first published works appeared in the 1470s and were distinguished by minute scholarship. During that decade he moved to Urbino and became ducal librarian, although he was to move between there and other parts of Italy thereafter as a teacher.

Zeus and the Tortoise appears among Aesop's Fables and explains how the tortoise got her shell. It is numbered 106 in the Perry Index. From it derives the proverbial sentiment that 'There's no place like home'.

Still waters run deep is a proverb of Latin origin now commonly taken to mean that a placid exterior hides a passionate or subtle nature. Formerly it also carried the warning that silent people are dangerous, as in Suffolk's comment on a fellow lord in William Shakespeare's play Henry VI part 2:

The labyrinth of Versailles was a hedge maze in the Gardens of Versailles with groups of fountains and sculptures depicting Aesop's Fables. André Le Nôtre initially planned a maze of unadorned paths in 1665, but in 1669, Charles Perrault advised Louis XIV to include thirty-nine fountains, each representing one of the fables of Aesop. Labyrinth The work was carried out between 1672 and 1677. Water jets spurting from the animals mouths were conceived to give the impression of speech between the creatures. There was a plaque with a caption and a quatrain written by the poet Isaac de Benserade next to each fountain. A detailed description of the labyrinth, its fables and sculptures is given in Perrault's Labyrinte de Versailles, illustrated with engravings by Sébastien Leclerc.

The phrase out of the frying pan into the fire is used to describe the situation of moving or getting from a bad or difficult situation to a worse one, often as the result of trying to escape from the bad or difficult one. It was the subject of a 15th-century fable that eventually entered the Aesopic canon.

The Walnut Tree is one of Aesop's fables and numbered 250 in the Perry Index. It later served as a base for a misogynistic proverb, which encourages the violence against walnut trees, asses and women.

The Hawk and the Nightingale is one of the earliest fables recorded in Greek and there have been many variations on the story since Classical times. The original version is numbered 4 in the Perry Index and the later Aesop version, sometimes going under the title "The Hawk, the Nightingale and the Birdcatcher", is numbered 567. The stories began as a reflection on the arbitrary use of power and eventually shifted to being a lesson in the wise use of resources.

The Fox and the Cat is an ancient fable, with both Eastern and Western analogues involving different animals, that addresses the difference between resourceful expediency and a master stratagem. Included in collections of Aesop's fables since the start of printing in Europe, it is number 605 in the Perry Index. In the basic story a cat and a fox discuss how many tricks and dodges they have. The fox boasts that he has many; the cat confesses to having only one. When hunters arrive with their dogs, the cat climbs a tree, but the fox thinks of many ways without acting and is caught by the hounds. Many morals have been drawn from the fable's presentations through history and, as Isaiah Berlin's use of it in his essay "The Hedgehog and the Fox" shows, it continues to be interpreted anew.

The young man and the swallow is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 169 in the Perry Index. It is associated with the ancient proverb 'One swallow doesn't make a summer'.

The Crow or Raven and the Snake or Serpent is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 128 in the Perry Index. Alternative Greek versions exist and two of these were adopted during the European Renaissance. The fable is not to be confused with the story of this title in the Panchatantra, which is completely different.

The Travellers and the Plane Tree is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 175 in the Perry Index. It may be compared with The Walnut Tree as having for theme ingratitude for benefits received. In this story two travellers rest from the sun under a plane tree. One of them describes it as useless and the tree protests at this view when they are manifestly benefiting from its shade.

The Ass and his Masters is a fable that has also gone by the alternative titles The ass and the gardener and Jupiter and the ass. Included among Aesop's Fables, it is numbered 179 in the Perry Index.

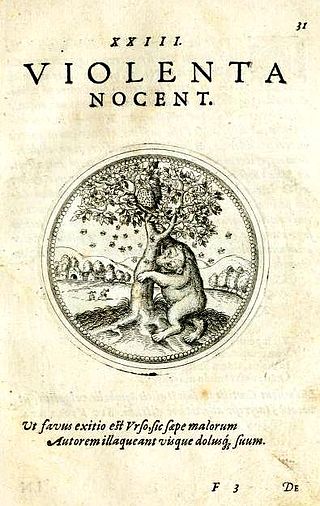

The Bear and the Bees is a fable of North Italian origin that became popular in other countries between the 16th - 19th centuries. There it has often been ascribed to Aesop's fables, although there is no evidence for this and it does not appear in the Perry Index. Various versions have been given different interpretations over time and artistic representations have been common.

There are no less than six fables concerning an impertinent insect, which is taken in general to refer to the kind of interfering person who makes himself out falsely to share in the enterprise of others or to be of greater importance than he is in reality. Some of these stories are included among Aesop's Fables, while others are of later origin, and from them have been derived idioms in several languages.

The fable of the Eel and the Snake was originated by Laurentius Abstemius in his Hecatomythium (1490). Versions of it appeared in several European languages afterwards and in collections associated with Aesop's Fables.

The Oxen and the Creaking Cart is a situational fable ascribed to Aesop and is numbered 45 in the Perry Index. Originally directed against complainers, it was later linked with the proverb 'the worst wheel always creaks most' and aimed emblematically at babblers of all sorts.

The Wolf and the Shepherds is ascribed to Aesop's Fables and is numbered 453 in the Perry Index. Although related very briefly in the oldest source, some later authors have drawn it out at great length and moralised that perceptions differ according to circumstances.