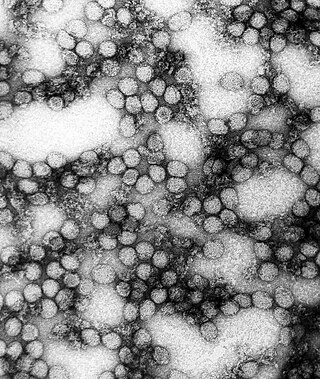

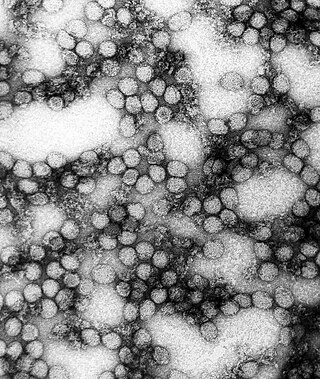

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains—particularly in the back—and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In about 15% of people, within a day of improving the fever comes back, abdominal pain occurs, and liver damage begins causing yellow skin. If this occurs, the risk of bleeding and kidney problems is increased.

Drapetomania was a supposed mental illness that, in 1851, American physician Samuel A. Cartwright hypothesized as the cause of enslaved Africans fleeing captivity. This hypothesis was based on the belief that slavery was such an improvement upon the lives of slaves that only those suffering from some form of mental illness would wish to escape.

In psychiatry, dysaesthesia aethiopica was an alleged mental illness described by American physician Samuel A. Cartwright in 1851, which proposed a theory for the cause of laziness among slaves. Today, dysaesthesia aethiopica is not recognized as a disease, but instead considered an example of pseudoscience, and part of the edifice of scientific racism.

The internal slave trade in the United States, also known as the domestic slave trade, the Second Middle Passage and the interregional slave trade, was the mercantile trade of enslaved people within the United States. It was most significant after 1808, when the importation of slaves from Africa was prohibited by federal law. Historians estimate that upwards of one million slaves were forcibly relocated from the Upper South, places like Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Missouri, to the territories and then-new states of the Deep South, especially Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas.

Josiah Clark Nott was an American surgeon, anthropologist and ethnologist. He is known for his studies into the etiology of yellow fever and malaria, including the theory that they are caused by germs, and for his espousal of scientific racism.

Samuel Adolphus Cartwright was an American physician who practiced in Mississippi and Louisiana in the antebellum United States. Cartwright is best known as the inventor of the 'mental illness' of drapetomania, the desire of a slave for freedom, and an outspoken opponent of germ theory.

The health of slaves on American plantations was a matter of concern to both slaves and their owners. Slavery had associated with it the health problems commonly associated with poverty. It was to the economic advantage of owners to keep their working slaves healthy, and those of reproductive age reproducing. Those who could not work or reproduce because of illness or age were sometimes abandoned by their owners, expelled from plantations, and left to fend for themselves.

Disease in colonial America that afflicted the early immigrant settlers was a dangerous threat to life. Some of the diseases were new and treatments were ineffective. Malaria was deadly to many new arrivals, especially in the Southern colonies. Of newly arrived able-bodied young men, over one-fourth of the Anglican missionaries died within five years of their arrival in the Carolinas. Mortality was high for infants and small children, especially for diphtheria, smallpox, yellow fever, and malaria. Most sick people turned to local healers, and used folk remedies. Others relied upon the minister-physicians, barber-surgeons, apothecaries, midwives, and ministers; a few used colonial physicians trained either in Britain, or an apprenticeship in the colonies. One common treatment was blood letting. The method was crude due to a lack of knowledge about infection and disease among medical practitioners. There was little government control, regulation of medical care, or attention to public health. By the 18th century, Colonial physicians, following the models in England and Scotland, introduced modern medicine to the cities in the 18th century, and made some advances in vaccination, pathology, anatomy and pharmacology.

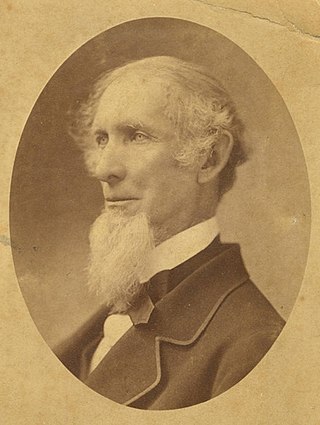

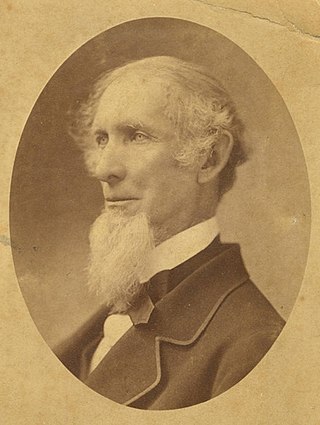

Dr. William Marbury Carpenter, a noted Southern natural scientist.

The evolutionary origins of yellow fever most likely came from Africa. Phylogenetic analyses indicate that the virus originated from East or Central Africa, with transmission between primates and humans, and spread from there to West Africa. The virus as well as the vector Aedes aegypti, a mosquito species, were probably brought to the western hemisphere and the Americas by slave trade ships from Africa after the first European exploration in 1492. However, some researchers have argued that yellow fever might have existed in the Americas during the pre-Columbian period as mosquitoes of the genus Haemagogus, which is indigenous to the Americas, have been known to carry the disease.

Night Doctors are bogeymen of African American folklore, resulting from some factual basis.

Jean Charles Faget was a medical doctor born on June 26, 1818, in New Orleans. He is best known for the Faget sign—a medical sign that is the unusual combination of fever and bradycardia. The sign is an important diagnostic symptom of yellow fever.

John Duffy (1915–1996) was an American medical historian who wrote books and scholarly journal articles on the history of medical education, public health and epidemics.

Bennet Dowler (1797-1879) was a physician and physiologist of the United States.

Victoria Angela Harden is an American medical historian who was the founding director of the Office of NIH History and the Stetten Museum at the National Institutes of Health. Most known for organizing conferences and publishing works on the history of HIV/AIDS, Harden also authored books on the history of the NIH and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. She is a past president of the Society for History in the Federal Government.

Richard Huck-Saunders was an English physician.

Moritz Schuppert was an American surgeon, anti-vaccinationist and early advocate of antisepsis.

The 1853 yellow fever epidemic of the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean islands resulted in thousands of fatalities. Over 9,000 people died of yellow fever in New Orleans alone, around eight percent of the total population. Many of the dead in New Orleans were recent Irish immigrants living in difficult conditions and without any acquired immunity. There was a stark racial disparity in mortality rates: "7.4 percent of whites who contracted yellow fever died, while only 0.2 percent of blacks perished from the disease." As historian Kathryn Olivarius observed in Necropolis: Disease, Power, and Capitalism in the Cotton Kingdom, "For enslaved Blacks, the story was different. Immunity protected them from yellow fever, but as embodied capital, they saw the social and monetary value of their acclimation accrued to their white owners."

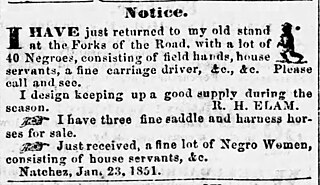

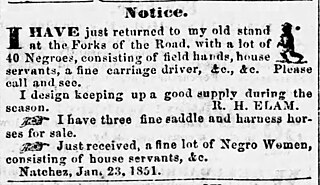

Robert H. Elam, usually advertising as R. H. Elam, was an American interstate slave trader who worked in Tennessee, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

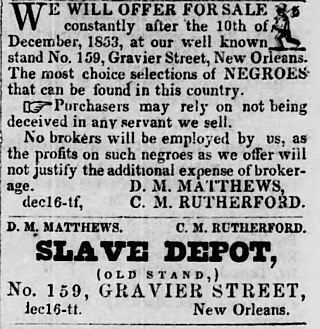

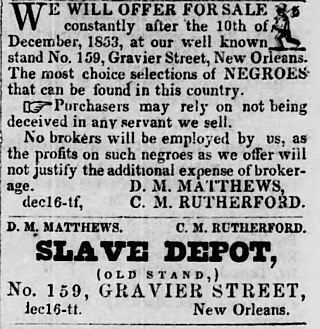

Calvin Morgan Rutherford, generally known as C. M. Rutherford, was a 19th-century American interstate slave trader. Rutherford had a wide geographic reach, trading nationwide from the Old Dominion of Virginia to as far west as Texas. Rutherford had ties to former Franklin & Armfield associates, worked in Kentucky for several years, advertised to markets throughout Louisiana and Mississippi, and was a major figure in the New Orleans slave trade for at least 20 years. Rutherford also invested his money in steamboats and hotels.