Modern paganism, also known as contemporary paganism and neopaganism, is a term for a religion or a family of religions which is influenced by the various historical pre-Christian beliefs of pre-modern peoples in Europe and adjacent areas of North Africa and the Near East. Although they share similarities, contemporary pagan movements are diverse and as a result, they do not share a single set of beliefs, practices, or texts. Scholars of religion often characterise these traditions as new religious movements. Some academics who study the phenomenon treat it as a movement that is divided into different religions while others characterize it as a single religion of which different pagan faiths are denominations.

Paganism is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity. In the time of the Roman empire, individuals fell into the pagan class either because they were increasingly rural and provincial relative to the Christian population, or because they were not milites Christi. Alternative terms used in Christian texts were hellene, gentile, and heathen. Ritual sacrifice was an integral part of ancient Graeco-Roman religion and was regarded as an indication of whether a person was pagan or Christian. Paganism has broadly connoted the "religion of the peasantry".

Ronald Edmund Hutton is an English historian who specialises in Early Modern Britain, British folklore, pre-Christian religion and Contemporary Paganism. He is a professor at the University of Bristol, has written 14 books and has appeared on British television and radio. He held a fellowship at Magdalen College, Oxford, and is a Commissioner of English Heritage.

Ernest Percival Rhys was a Welsh-English writer, best known for his role as founding editor of the Everyman's Library series of affordable classics. He wrote essays, stories, poetry, novels and plays.

William Sharp was a Scottish writer, of poetry and literary biography in particular, who from 1893 wrote also as Fiona Macleod, a pseudonym kept almost secret during his lifetime. He was also an editor of the poetry of Ossian, Walter Scott, Matthew Arnold, Algernon Charles Swinburne and Eugene Lee-Hamilton.

Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today is a sociological study of contemporary Paganism in the United States written by the American Wiccan and journalist Margot Adler. First published in 1979 by Viking Press, it was later republished in a revised and expanded edition by Beacon Press in 1986, with third and fourth revised editions being brought out by Penguin Books in 1996 and then 2006 respectively.

Chas S. Clifton is an American academic, author and historian who specialises in the fields of English studies and Pagan studies. Clifton currently holds a teaching position in English at Colorado State University-Pueblo, prior to which he taught at Pueblo Community College.

A Community of Witches: Contemporary Neo-Paganism and Witchcraft in the United States is a sociological study of the Wiccan and wider Pagan community in the Northeastern United States. It was written by American sociologist Helen A. Berger of the West Chester University of Pennsylvania and first published in 1999 by the University of South Carolina Press. It was released as a part of a series of academic books entitled Studies in Comparative Religion, edited by Frederick M. Denny, a religious studies scholar at the University of Chicago.

Pagan studies is the multidisciplinary academic field devoted to the study of modern paganism, a broad assortment of modern religious movements, which are typically influenced by or claiming to be derived from the various pagan beliefs of premodern Europe. Pagan studies embrace a variety of different scholarly approaches to studying such religions, drawing from history, sociology, anthropology, archaeology, folkloristics, theology and other religious studies.

Modern Paganism in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives is an academic anthology edited by the American religious studies scholar Michael F. Strmiska which was published by ABC-CLIO in 2005. Containing eight separate papers produced by various scholars working in the field of Pagan studies, the book examines different forms of contemporary Paganism as practiced in Europe and North America. Modern Paganism in World Cultures was published as a part of ABC-CLIO's series of books entitled 'Religion in Contemporary Cultures', in which other volumes were dedicated to religious movements like Buddhism and Islam.

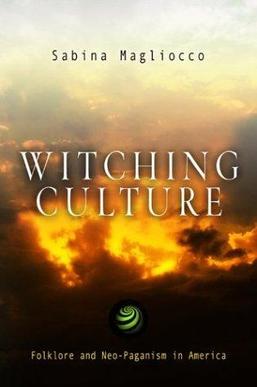

Witching Culture: Folklore and Neo-Paganism in America is a folkloric and anthropological study of the Wiccan and wider Pagan community in the United States. It was written by the American anthropologist and folklorist Sabina Magliocco of California State University, Northridge and first published in 2004 by the University of Pennsylvania Press. It was released as a part of a series of academic books titled 'Contemporary Ethnography', edited by the anthropologists Kirin Narayan of the University of Wisconsin and Paul Stoller of West Chester University.

Enchanted Feminism: The Reclaiming Witches of San Francisco is an anthropological study of the Reclaiming Wiccan community of San Francisco. It was written by the Scandinavian theologian Jone Salomonsen of the California State University, Northridge and first published in 2002 by the Routledge.

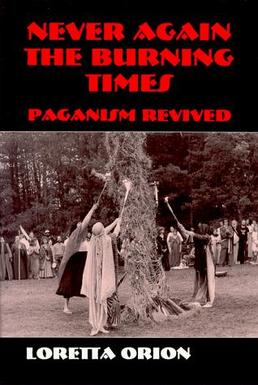

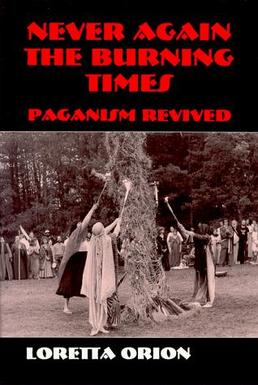

Never Again the Burning Times: Paganism Revisited is an anthropological study of the Wiccan and wider Pagan community in the United States. It was written by the American anthropologist Loretta Orion and published by Waveland Press in 1995.

Living Witchcraft: A Contemporary American Coven is a sociological study of an American coven of Wiccans who operated in Atlanta, Georgia during the early 1990s. It was co-written by the sociologist Allen Scarboro, psychologist Nancy Campbell and literary critic Shirley Stave and first published by Praeger in 1994. Although largely sociological, the study was interdisciplinary, and included both insider and outsider perspectives into the coven; Stave was an initiate and a practicing Wiccan while Scarboro and Campbell remained non-initiates throughout the course of their research.

Slavic Native Faith or Slavic Neopaganism in Russia is widespread, according to some estimates from research organisations which put the number of Russian Rodnovers in the millions. The Rodnover population generally has a high education and many of its exponents are intellectuals, many of whom are politically engaged both in the right and the left wings of the political spectrum. Particular movements that have arisen within Russian Rodnovery include various doctrinal frameworks such as Anastasianism, Authentism, Bazhovism, Ivanovism, Kandybaism, Levashovism, Peterburgian Vedism, Slavic-Hill Rodnovery, Vseyasvetnaya Gramota, the Way of Great Perfection, the Way of Troyan, and Ynglism, as well as various attempts to construct specific ethnic Rodnoveries, such as Krivich Rodnovery, Meryan Rodnovery, Viatich Rodnovery. Rodnovery in Russia is also influenced by, and in turn influences, movements that have their roots in Russian cosmism and identify themselves as belonging to the same Vedic culture, such as Roerichism and Blagovery.

Elizabeth Amelia Sharp (1856–1932) was a critic, editor and writer, and married to the Scottish writer, William Sharp also known by his pseudonym Fiona MacLeod. William Sharp (1855–1905) was her first cousin, his father David was a younger brother of Thomas, Elizabeth's father. They had no children.

Joseph Marshall Stoddart, was an American business man, Editor of Lippincott's Monthly Magazine from 1886 to 1894 and later of the New Science Review.

Modern pagan music or neopagan music is music created for or influenced by modern Paganism. This music is produced in the interwar period and includes efforts from the Latvian Dievturība movement and the Norwegian composer Geirr Tveitt. The counterculture of the 1960s established British folk revival and world music as influences for American neopagan music. Second-wave feminism created women's music which includes influences from feminist versions of neopaganism. The United States also produced Moondog, a Norse neopagan street musician and composer. The postwar neopagan organisations Ásatrúarfélagið in Iceland and Romuva in Lithuania have been led by musicians.

Modern paganism and New Age are eclectic new religious movements with similar decentralised structures but differences in their views of history, nature, and goals of the practitioner. Modern pagan movements, which often have roots in 18th- and 19th-century cultural movements, seek to revive or be influenced by historical pagan beliefs. New Age teachings emerged in the second half of the 20th century and are characterised by millenarian ideas about spiritual advancement. Since the counterculture of the 1960s, there has been interaction, mutual influence, and often confusion in the popular mind between the movements.

Modern paganism, also known as contemporary paganism and neopaganism, is a collective term for new religious movements which are influenced by or derived from the various historical pagan beliefs of pre-modern peoples. Although they share similarities, contemporary pagan religious movements are diverse, and as a result, they do not share a single set of beliefs, practices, or texts.