Clairvoyance is the claimed ability to acquire information that would be considered impossible to get through scientifically proven sensations, thus classified as extrasensory perception, or "sixth sense". Any person who is claimed to have such ability is said to be a clairvoyant.

Extrasensory perception (ESP), also known as a sixth sense, or cryptaesthesia, is a claimed paranormal ability pertaining to reception of information not gained through the recognized physical senses, but sensed with the mind. The term was adopted by Duke University botanist J. B. Rhine to denote psychic abilities such as intuition, telepathy, psychometry, clairvoyance, clairaudience, clairsentience, empathy and their trans-temporal operation as precognition or retrocognition.

Parapsychology is the study of alleged psychic phenomena and other paranormal claims, for example, those related to near-death experiences, synchronicity, apparitional experiences, etc. Criticized as being a pseudoscience, the majority of mainstream scientists reject it. Parapsychology has also been criticized by mainstream critics for claims by many of its practitioners that their studies are plausible despite a lack of convincing evidence after more than a century of research for the existence of any psychic phenomena.

Parapsychology is a field of research that studies a number of ostensible paranormal phenomena, including telepathy, precognition, clairvoyance, psychokinesis, near-death experiences, reincarnation, and apparitional experiences.

Telepathy is the purported vicarious transmission of information from one person's mind to another's without using any known human sensory channels or physical interaction. The term was first coined in 1882 by the classical scholar Frederic W. H. Myers, a founder of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR), and has remained more popular than the earlier expression thought-transference.

A ganzfeld experiment is an assessment used by parapsychologists that they contend can test for extrasensory perception (ESP) or telepathy. In these experiments, a "sender" attempts to mentally transmit an image to a "receiver" who is in a state of sensory deprivation. The receiver is normally asked to choose between a limited number of options for what the transmission was supposed to be and parapsychologists who propose that such telepathy is possible argue that rates of success above the expectation from randomness are evidence for ESP. Consistent, independent replication of ganzfeld experiments has not been achieved, and, in spite of strenuous arguments by parapsychologists to the contrary, there is no validated evidence accepted by the wider scientific community for the existence of any parapsychological phenomena. Ongoing parapsychology research using ganzfeld experiments has been criticized by independent reviewers as having the hallmarks of pseudoscience.

Remote viewing (RV) is the practice of seeking impressions about a distant or unseen subject, purportedly sensing with the mind. A remote viewer is expected to give information about an object, event, person, or location hidden from physical view and separated at some distance. Physicists Russell Targ and Harold Puthoff, parapsychology researchers at Stanford Research Institute (SRI), are generally credited with coining the term "remote viewing" to distinguish it from the closely related concept of clairvoyance. According to Targ, the term was first suggested by Ingo Swann in December 1971 during an experiment at the American Society for Psychical Research in New York City.

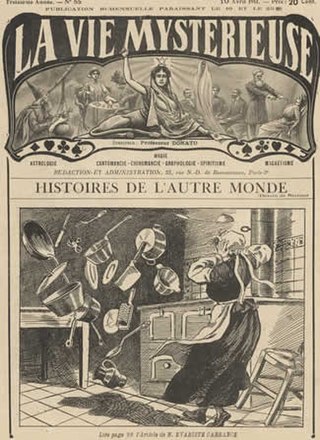

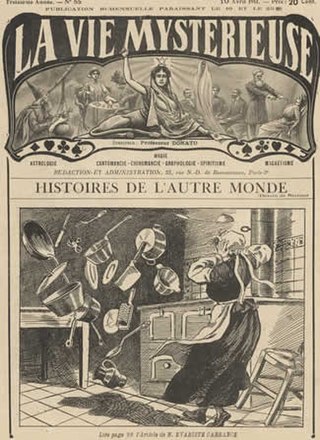

Paranormal events are purported phenomena described in popular culture, folk, and other non-scientific bodies of knowledge, whose existence within these contexts is described as being beyond the scope of normal scientific understanding. Notable paranormal beliefs include those that pertain to extrasensory perception, spiritualism and the pseudosciences of ghost hunting, cryptozoology, and ufology.

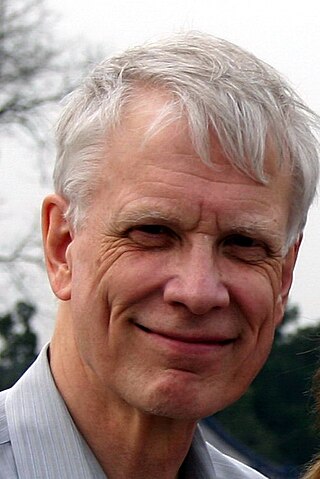

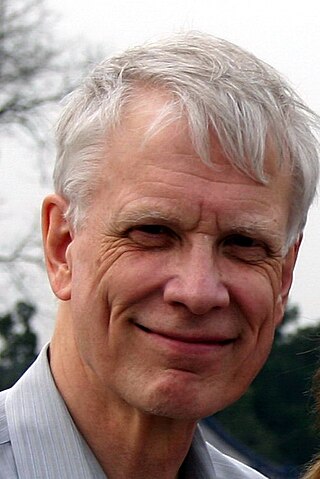

Dean Radin investigates phenomena in parapsychology. Following a bachelor and master's degree in electrical engineering and a PhD in educational psychology Radin worked at Bell Labs, as a researcher at Princeton University and the University of Edinburgh, and was a faculty member at University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He then became Chief Scientist at the Institute of Noetic Sciences (IONS) in Petaluma, California, USA, later becoming the president of the Parapsychological Association. He is also co-editor-in-chief of the journal Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing. Radin's ideas and work have been criticized by scientists and philosophers skeptical of paranormal claims. The review of Radin's first book, The Conscious Universe, that appeared in Nature charged that Radin ignored the known hoaxes in the field, made statistical errors and ignored plausible non-paranormal explanations for parapsychological data.

Jessica Utts is a parapsychologist and statistics professor at the University of California, Irvine. She is known for her textbooks on statistics and her investigation into remote viewing.

Charles Henry Honorton was an American parapsychologist and was one of the leaders of a collegial group of researchers who were determined to apply established scientific research methods to the examination of what they called "anomalous information transfer" and other phenomena associated with the "mind/body problem"—the idea that mind might, at least in some respects, have a physical existence independent of the body.

David Francis Marks is a psychologist, author and editor of numerous articles and books concerned mainly with five areas of psychological research – judgement, health psychology, consciousness, parapsychology and intelligence. Marks is also the originator of the General Theory of Behaviour and has curated exhibitions and books about artists and their works.

Stephen E. Braude is an American philosopher and parapsychologist. He is a past president of the Parapsychological Association, Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Scientific Exploration, and a professor of philosophy at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

James E. Alcock is Professor emeritus (Psychology) at York University (Canada). Alcock is a noted critic of parapsychology and a Fellow and Member of the Executive Council for the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. He is a member of the Editorial Board of The Skeptical Inquirer, and a frequent contributor to the magazine. He has also been a columnist for Humanist Perspectives Magazine. In 1999, a panel of skeptics named him among the two dozen most outstanding skeptics of the 20th century. In May 2004, CSICOP awarded Alcock CSI's highest honor, the In Praise of Reason Award. The author of several books and peer reviewed journal articles, Alcock is also an amateur magician and a member of the International Brotherhood of Magicians.

Etzel Cardeña is the Thorsen Professor of Psychology at Lund University, Sweden where he is Director of the Centre for Research on Consciousness and Anomalous Psychology (CERCAP). He has served as President of the Society of Psychological Hypnosis, and the Society for Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. He is the current editor of the Journal of Parapsychology. He has expressed views in favour of what he terms "an open, informed study on all aspects of consciousness" and the validity of some paranormal phenomena. The Parapsychological Association honored Cardeña with the 2013 Charles Honorton Integrative Contributions Award. His publications include the books Altering Consciousness and Varieties of Anomalous Experience.

In psychology, anomalistic psychology is the study of human behaviour and experience connected with what is often called the paranormal, with few assumptions made about the validity of the reported phenomena.

Gardner Murphy was an American psychologist who specialized in social and personality psychology and parapsychology. His career highlights include serving as president of the American Psychological Association and the British Society for Psychical Research.

Telekinesis is a purported psychic ability allowing an individual to influence a physical system without physical interaction. Experiments to prove the existence of telekinesis have historically been criticized for lack of proper controls and repeatability. There is no reliable evidence that telekinesis is a real phenomenon, and the topic is generally regarded as pseudoscience.

Charles Edward Mark Hansel was a British psychologist most notable for his criticism of parapsychological studies.

The Psychology of the Occult is a 1952 skeptical book on the paranormal by psychologist D. H. Rawcliffe. It was later published as Illusions and Delusions of the Supernatural and the Occult (1959) and Occult and Supernatural Phenomena (1988) by Dover Publications. Biologist Julian Huxley wrote a foreword to the book.