The Savoy Ballroom was a large ballroom for music and public dancing located at 596 Lenox Avenue, between 140th and 141st Streets in the Harlem neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. Lenox Avenue was the main thoroughfare through upper Harlem. Poet Langston Hughes calls it the "Heartbeat of Harlem" in Juke Box Love Song, and he set his work "Lenox Avenue: Midnight" on the legendary street. The Savoy was one of many Harlem hot spots along Lenox, but it was the one to be called the "World's Finest Ballroom". It was in operation from March 12, 1926, to July 10, 1958, and as Barbara Englebrecht writes in her article "Swinging at the Savoy", it was "a building, a geographic place, a ballroom, and the 'soul' of a neighborhood". It was opened and owned by white entrepreneur Jay Faggen and Jewish businessman Moe Gale. It was managed by African-American businessman and civic leader Charles Buchanan. Buchanan, who was born in the British West Indies, sought to run a "luxury ballroom to accommodate the many thousands who wished to dance in an atmosphere of tasteful refinement, rather than in the small stuffy halls and the foul smelling, smoke laden cellar nightclubs ..."

The Charleston is a dance named after the harbor city of Charleston, South Carolina. The rhythm was popularized in mainstream dance music in the United States by a 1923 tune called "The Charleston" by composer/pianist James P. Johnson, which originated in the Broadway show Runnin' Wild and became one of the most popular hits of the decade. Runnin' Wild ran from 28 October 1923 through 28 June 1924. The Charleston dance's peak popularity occurred from mid-1926 to 1927.

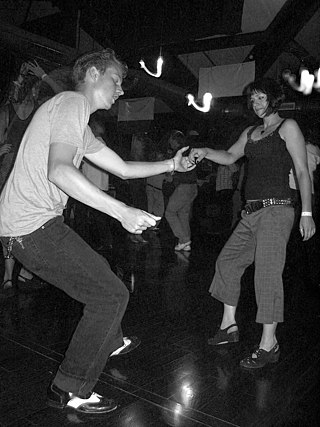

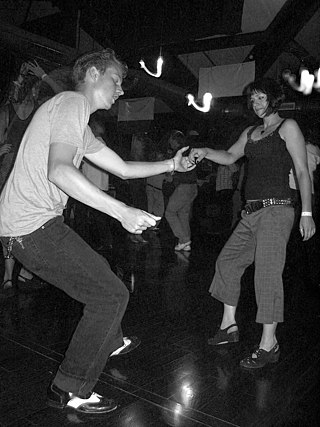

Swing dance is a group of social dances that developed with the swing style of jazz music in the 1920s–1940s, with the origins of each dance predating the popular "swing era". Hundreds of styles of swing dancing were developed; those that have survived beyond that era include Charleston, Balboa, Lindy Hop, and Collegiate Shag. Today, the best-known of these dances is the Lindy Hop, which originated in Harlem in the early 1930s. While the majority of swing dances began in African-American communities as vernacular African-American dances, some influenced swing-era dances, like Balboa, developed outside of these communities.

Swing music is a style of jazz that developed in the United States during the late 1920s and early 1930s. It became nationally popular from the mid-1930s. Swing bands usually featured soloists who would improvise on the melody over the arrangement. The danceable swing style of big bands and bandleaders such as Benny Goodman was the dominant form of American popular music from 1935 to 1946, known as the swing era, when people were dancing the Lindy Hop. The verb "to swing" is also used as a term of praise for playing that has a strong groove or drive. Musicians of the swing era include Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Count Basie, Cab Calloway, Benny Carter, Jimmy Dorsey, Tommy Dorsey, Woody Herman, Earl Hines, Bunny Berigan, Harry James, Lionel Hampton, Glenn Miller, Artie Shaw, Jimmie Lunceford, and Django Reinhardt.

Frank Manning was an American dancer, instructor, and choreographer. Manning is considered one of the founders of Lindy Hop, an energetic form of the jazz dance style known as swing.

Blues dancing is a family of historical dances that developed alongside and were danced to blues music, or the contemporary dances that are danced in that aesthetic. It has its roots in African-American dance, which itself is rooted in sub-Saharan African music traditions and the historical dances brought to the United States by European immigrants.

The Hot Shots is a collective name for two closely related Swedish dance companies based in Stockholm, Sweden: The Rhythm Hot Shots and the Harlem Hot Shots. The Hot Shots specialize in faithful reproductions of African-American dance scenes in American films from the 1920s, 30s, and 40s. Dances that they perform include Lindy Hop, Tap dance, Cakewalk, Charleston, and Black Bottom. The members of the Hot Shots are also respected dance instructors and accomplished social dancers. The goals of The Rhythm Hot Shots and the Harlem Hot Shots are the same.

Dean Collins was an American dancer, instructor, choreographer, and innovator of swing dance. He is often credited with bringing the Lindy Hop from New York to southern California and influencing the development of West Coast Swing. Collins worked in over thirty films and performed live and on television.

Whitey's Lindy Hoppers was a professional performing group of exceptional swing dancers that was first organized in the late 1920s by Herbert "Whitey" White in the Savoy Ballroom and disbanded in 1942 after its male members were drafted into World War II. The group, taking on many different forms and sub-groups, including Whitey's Hopping Maniacs, Harlem Congeroo Dancers, and The Hot Chocolates, were inspired by the choreography of Frankie Manning.In addition to touring nationally and internationally, the group appeared in several films and Broadway theatre productions. Dorothy Dandridge and Sammy Davis Jr. were among the group's celebrity regulars.

Al Minns, was a prominent American Lindy Hop and jazz dancer. Most famous for his film and stage performances in the 1930s and 1940s with the Harlem-based Whitey's Lindy Hoppers, Minns worked throughout his life to promote the dances that he and his cohorts helped to pioneer at New York's Savoy Ballroom. In 1938, Al Minns and Sandra Gibson won the Harvest Moon Ball.

Alfred "Pepsi" Bethel was a jazz dancer, choreographer, and leader of his own dance troupe, the Pepsi Bethel Authentic Jazz Dance Theater, which he founded in 1960.

George "Shorty" Snowden was an African American dancer in Harlem during the 1920s and 1930s. He and his partner Mattie Purnell invented the Harlem Lindy Hop in the dance marathon at Harlem's Rockland Palace between June and July 1928. Snowden and Purnell's invention was based on the breakaway pattern which they practically rediscovered via an accident in the dance marathon.

The history of Lindy Hop begins in the African American communities of Harlem, New York during the late 1920s in conjunction with swing jazz. Lindy Hop is closely related to earlier African American vernacular dances but quickly gained its own fame through dancers in films, performances, competitions, and professional dance troupes. It became especially popular in the 1930s with the upsurge of aerials. The popularity of Lindy Hop declined after World War II, and it converted to other forms of dancing, but it never disappeared during the decades between the 1940s and the 1980s until European and American dancers revived it starting from the beginning of the 1980s.

Norma Adele Miller was an American Lindy hop dancer, choreographer, actress, author, and comedian known as the "Queen of Swing".

Mura Ziperovitch Dehn (1905–1987) documented African-American social jazz dancing at the Savoy Ballroom in New York in the 1930s and 1940s, a time that she referred to as the "Golden Age of Jazz." She also worked as a producer and documenter up until her death, and was co-artistic director of Traditional Jazz Dance Theater, along with vaudeville performer James Berry.

Al & Leon were a prominent American Lindy Hop and jazz dance duo. The two members were Al Minns and Leon James. They were most famous for their film and stage performances in the 1930s and 1940s both on their own, and as part of the Harlem-based Whitey's Lindy Hoppers. They appeared in the Marx Brothers film A Day at the Races. They also appeared on US television programs in the 1950s and 1960s, highlighting the jazz dances they and their cohorts helped to pioneer at the Savoy Ballroom in New York, as well as working throughout their lives to promote the dances to new generations.

The Lindy Hop is an American dance which was born in the African-American communities of Harlem, New York City, in 1928 and has evolved since then. It was very popular during the swing era of the late 1930s and early 1940s. Lindy is a fusion of many dances that preceded it or were popular during its development but is mainly based on jazz, tap, breakaway, and Charleston. It is frequently described as a jazz dance and is a member of the swing dance family.

Dawn Hampton was an American cabaret and jazz singer, saxophonist, dancer, and songwriter. Hampton began her lifelong career as a musical entertainer touring the Midwest as a three-year-old member of the Hampton family's band The Hampton Sisters in the late 1930s. During World War II and into early 1950s, she performed as part of a quartet with her three sisters and in a jazz band with all nine of her surviving siblings. Hampton moved to New York City in 1958 to pursue a solo career as a cabaret singer. She became a singer/songwriter and dancer, which included off-Broadway theatre performances and swing dancing in Hollywood films. Along with other members of the musical Hamptons, she was a recipient of the State of Indiana's Governor Arts Award (1991) and honored at the Indy Jazz Fest (2000) in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Willa Mae Ricker was a prominent American Lindy Hop and jazz dancer and performer during the 1930s and 1940s with the Harlem-based Whitey's Lindy Hoppers. She was known for her physical strength, fashion sense, dependability, business acumen, and passion to dance. According to Norma Miller, Ricker was the first dancer to stand up to Herbert "Whitey" White, demanding fair pay.

Roger Pryor Dodge was an American ballet, vaudeville, and jazz dancer, as well as a choreographer and pioneering jazz critic. He formed the first extensive collection of photographic portraits of Vaslav Nijinsky.