Mars, the fourth planet from the Sun, has appeared as a setting in works of fiction since at least the mid-1600s. Trends in the planet's portrayal have largely been influenced by advances in planetary science. It became the most popular celestial object in fiction in the late 1800s, when it became clear that there was no life on the Moon. The predominant genre depicting Mars at the time was utopian fiction. Around the same time, the mistaken belief that there are canals on Mars emerged and made its way into fiction, popularized by Percival Lowell's speculations of an ancient civilization having constructed them. The War of the Worlds, H. G. Wells's novel about an alien invasion of Earth by sinister Martians, was published in 1897 and went on to have a major influence on the science fiction genre.

Tik-Tok is a 1983 science fiction novel by American writer John Sladek. It received a 1983 British Science Fiction Association Award.

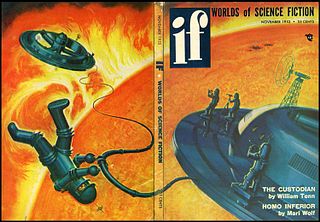

The planet Venus has been used as a setting in fiction since before the 19th century. Its opaque cloud cover gave science fiction writers free rein to speculate on conditions at its surface—a "cosmic Rorschach test", in the words of science fiction author Stephen L. Gillett. The planet was often depicted as warmer than Earth but still habitable by humans. Depictions of Venus as a lush, verdant paradise, an oceanic planet, or fetid swampland, often inhabited by dinosaur-like beasts or other monsters, became common in early pulp science fiction, particularly between the 1930s and 1950s. Some other stories portrayed it as a desert, or invented more exotic settings. The absence of a common vision resulted in Venus not developing a coherent fictional mythology, in contrast to the image of Mars in fiction.

The Moon has appeared in fiction as a setting since at least classical antiquity. Throughout most of literary history, a significant portion of works depicting lunar voyages has been satirical in nature. From the late 1800s onwards, science fiction has successively focused largely on the themes of life on the Moon, first Moon landings, and lunar colonization.

Fictional depictions of Mercury, the innermost planet of the Solar System, have gone through three distinct phases. Before much was known about the planet, it received scant attention. Later, when it was incorrectly believed that it was tidally locked with the Sun creating a permanent dayside and nightside, stories mainly focused on the conditions of the two sides and the narrow region of permanent twilight between. Since that misconception was dispelled in the 1960s, the planet has again received less attention from fiction writers, and stories have largely concentrated on the harsh environmental conditions that come from the planet's proximity to the Sun.

Saturn has made appearances in fiction since the 1752 novel Micromégas by Voltaire. In the earliest depictions, it was portrayed as having a solid surface rather than its actual gaseous composition. In many of these works, the planet is inhabited by aliens that are usually portrayed as being more advanced than humans. In modern science fiction, the Saturnian atmosphere sometimes hosts floating settlements. The planet is occasionally visited by humans and its rings are sometimes mined for resources.

Asteroids have appeared in fiction since at least the late 1800s, the first one—Ceres—having been discovered in 1801. They were initially only used infrequently as writers preferred the planets as settings. The once-popular Phaëton hypothesis, which states that the asteroid belt consists of the remnants of the former fifth planet that existed in an orbit between Mars and Jupiter before somehow being destroyed, has been a recurring theme with various explanations for the planet's destruction proposed. This hypothetical former planet is in science fiction often called "Bodia" in reference to Johann Elert Bode, for whom the since-discredited Titius–Bode law that predicts the planet's existence is named.

Neptune has appeared in fiction since shortly after its 1846 discovery, albeit infrequently. It initially made appearances indirectly—e.g. through its inhabitants—rather than as a setting. The earliest stories set on Neptune itself portrayed it as a rocky planet rather than as having its actual gaseous composition; later works rectified this error. Extraterrestrial life on Neptune is uncommon in fiction, though the exceptions have ranged from humanoids to gaseous lifeforms. Neptune's largest moon Triton has also appeared in fiction, especially in the late 20th century onwards.

In science fiction, a time viewer, temporal viewer, or chronoscope is a device that allows another point in time to be observed. The concept has appeared since the late 19th century, constituting a significant yet relatively obscure subgenre of time travel fiction and appearing in various media including literature, cinema, and television. Stories usually explain the technology by referencing cutting-edge science, though sometimes invoking the supernatural instead. Most commonly only the past can be observed, though occasionally time viewers capable of showing the future appear; these devices are sometimes limited in terms of what information about the future can be obtained. Other variations on the concept include being able to listen to the past but not view it.

Jane Gaskell is a British fantasy writer.

Planets outside of the Solar System have appeared in fiction since at least the 1850s, long before the first real ones were discovered in the 1990s. Most of these fictional planets do not differ significantly from the Earth, and serve only as settings for the narrative. The majority host native lifeforms, sometimes with humans integrated into the ecosystems. Fictional planets that are not Earth-like vary in many different ways. They may have significantly stronger or weaker gravity on their surfaces, or have a particularly hot or cold climate. Both desert planets and ocean planets appear, as do planets with unusual chemical conditions. Various peculiar planetary shapes have been depicted, including flattened, cubic, and toroidal. Some fictional planets exist in multiple-star systems where the orbital mechanics can lead to exotic day–night or seasonal cycles, while others do not orbit any star at all. More fancifully, planets are occasionally portrayed as having sentience, though this is less common than stars receiving the same treatment or a planet's lifeforms having a collective consciousness.

Stars outside of the Solar System have been featured as settings in works of fiction since at least the 1600s, though this did not become commonplace until the pulp era of science fiction. Stars themselves are rarely a point of focus in fiction, their most common role being an indirect one as hosts of planetary systems. In stories where stars nevertheless do get specific attention, they play a variety of roles. Their appearance as points of light in the sky is significant in several stories where there are too many, too few, or an unexpected arrangement of them; in fantasy, they often serve as omens. Stars also appear as sources of power, be it the heat and light of their emanating radiation or superpowers. Certain stages of stellar evolution have received particular attention: supernovae, neutron stars, and black holes. Stars being depicted as sentient beings—whether portrayed as supernatural entities, personified in human form, or simply anthropomorphized as having intelligence—is a recurring theme. Real stars occasionally make appearances in science fiction, especially the nearest: the Alpha Centauri system, often portrayed as the destination of the first interstellar voyage. Tau Ceti, a relatively-nearby star regarded as a plausible candidate for harbouring habitable planets, is also popular.

Black holes, objects whose gravity is so strong that nothing—including light—can escape them, have been depicted in fiction since at least the pulp era of science fiction, before the term black hole was coined. A common portrayal at the time was of black holes as hazards to spacefarers, a motif that has also recurred in later works. The concept of black holes became popular in science and fiction alike in the 1960s. Authors quickly seized upon the relativistic effect of gravitational time dilation, whereby time passes more slowly closer to a black hole due to its immense gravitational field. Black holes also became a popular means of space travel in science fiction, especially when the notion of wormholes emerged as a relatively plausible way to achieve faster-than-light travel. In this concept, a black hole is connected to its theoretical opposite, a so-called white hole, and as such acts as a gateway to another point in space which might be very distant from the point of entry. More exotically, the point of emergence is occasionally portrayed as another point in time—thus enabling time travel—or even an entirely different universe.

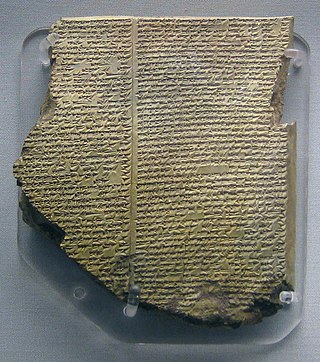

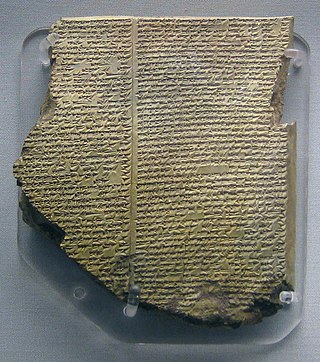

Immortality is a common theme in fiction. The concept has been depicted since the Epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest known work of fiction. Originally appearing in the domain of mythology, it has later become a recurring element in the genres of horror, science fiction, and fantasy. For most of literary history, the dominant perspective has been that the desire for immortality is misguided, albeit strong; among the posited drawbacks are ennui, loneliness, and social stagnation. This view was challenged in the 20th century by writers such as George Bernard Shaw and Roger Zelazny. Immortality is commonly obtained either from supernatural entities or objects such as the Fountain of Youth or through biological or technological means such as brain transplants.

Supernovae, extremely powerful explosions of stars, have been featured in works of fiction since at least the early 1900s. The idea that the Sun could explode in this manner has served as the basis for many stories about disaster striking Earth, though it is now recognized that this cannot actually happen. Recurring themes in these stories include anticipating the inevitable destruction while being helpless and evacuating the planet, sometimes with the assistance of helpful aliens. The destruction of Earth in this manner occasionally serves as backstory explaining why humanity has started colonizing the cosmos. Another recurring scenario is radiation from more distant supernovae threatening Earth. Besides humans, alien civilizations are also occasionally subject to the dangers of supernovae. Supernovae are induced intentionally in several works, typically for use as weapons but sometimes for more peaceful purposes, and naturally occurring supernovae are likewise exploited in some stories.

Thorns is a science fiction novel by American author Robert Silverberg, published as a paperback original in 1967, and a Nebula and Hugo Awards nominee.

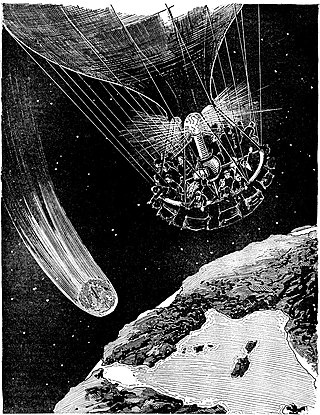

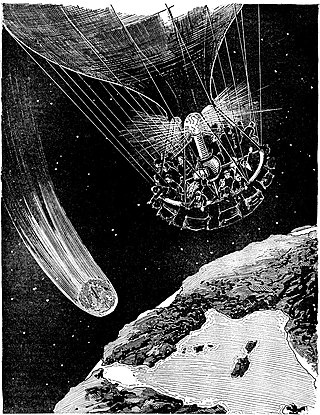

Comets have appeared in works of fiction since at least the 1830s. They primarily appear in science fiction as literal objects, but also make occasional symbolical appearances in other genres. In keeping with their traditional cultural associations as omens, they often threaten destruction to Earth. This commonly comes in the form of looming impact events, and occasionally through more novel means such as affecting Earth's atmosphere in different ways. In other stories, humans seek out and visit comets for purposes of research or resource extraction. Comets are inhabited by various forms of life ranging from microbes to vampires in different depictions, and are themselves living beings in some stories.

The Windsingers is the debut fantasy series of American author Robin Hobb under her pen name Megan Lindholm, published between 1983 and 1989. It follows a woman named Ki as she recovers from the death of her family and forms a companionship with a man called Vandien. Over the course of four books, the duo face fictional creatures including harpies, who can grant visions of the dead, and Windsingers, beings who can control the weather through music. The characters Ki and Vandien first appeared in a short story in Amazons!, an anthology focused on female heroes in fantasy. The anthology won a World Fantasy Award in 1980, and Lindholm's story drew the interest of an editor at Ace Books, leading to the development of the series.

The Sun has appeared as a setting in fiction at least since classical antiquity, but for a long time it received relatively sporadic attention. Many of the early depictions viewed it as an essentially Earth-like and thus potentially habitable body—a once-common belief about celestial objects in general known as the plurality of worlds—and depicted various kinds of solar inhabitants. As more became known about the Sun through advances in astronomy, in particular its temperature, solar inhabitants fell out of favour save for the occasional more exotic alien lifeforms. Instead, many stories focused on the eventual death of the Sun and the havoc it would wreak upon life on Earth. Before it was understood that the Sun is powered by nuclear fusion, the prevailing assumption among writers was that combustion was the source of its heat and light, and it was expected to run out of fuel relatively soon. Even after the true source of the Sun's energy was determined in the 1920s, the dimming or extinction of the Sun remained a recurring theme in disaster stories, with occasional attempts at averting disaster by reigniting the Sun. Another common way for the Sun to cause destruction is by exploding, and other mechanisms such as solar flares also appear on occasion.

Neutron stars—extremely dense remnants of stars that have undergone supernova events—have appeared in fiction since the 1960s. Their immense gravitational fields and resulting extreme tidal forces are a recurring point of focus. Some works depict the neutron stars as harbouring exotic alien lifeforms, while others focus on the habitability of the surrounding system of planets. Neutron star mergers, and their potential to cause extinction events at interstellar distances due to the enormous amounts of radiation released, also feature on occasion. Neutronium, the degenerate matter that makes up neutron stars, often turns up as a material existing outside of them in science fiction; in reality, it would likely not be stable.