Siegfried Fred Singer was an Austrian-born American physicist and emeritus professor of environmental science at the University of Virginia, trained as an atmospheric physicist. He was known for rejecting the scientific consensus on several issues, including climate change, the connection between UV-B exposure and melanoma rates, stratospheric ozone loss being caused by chlorofluoro compounds, often used as refrigerants, and the health risks of passive smoking.

Richard Siegmund Lindzen is an American atmospheric physicist known for his work in the dynamics of the middle atmosphere, atmospheric tides, and ozone photochemistry. He is the author of more than 200 scientific papers. From 1972 to 1982, he served as the Gordon McKay Professor of Dynamic Meteorology at Harvard University. In 1983, he was appointed as the Alfred P. Sloan Professor of Meteorology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he would remain until his retirement in 2013. Lindzen has disputed the scientific consensus on climate change and criticizes what he has called "climate alarmism".

National Review is an American conservative editorial magazine, focusing on news and commentary pieces on political, social, and cultural affairs. The magazine was founded by William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955. Its editor-in-chief is Rich Lowry, and its editor is Ramesh Ponnuru.

Global cooling was a conjecture, especially during the 1970s, of imminent cooling of the Earth culminating in a period of extensive glaciation, due to the cooling effects of aerosols or orbital forcing. Some press reports in the 1970s speculated about continued cooling; these did not accurately reflect the scientific literature of the time, which was generally more concerned with warming from an enhanced greenhouse effect.

Michael Evan Mann is an American climatologist and geophysicist. He is the director of the Center for Science, Sustainability & the Media at the University of Pennsylvania. Mann has contributed to the scientific understanding of historic climate change based on the temperature record of the past thousand years. He has pioneered techniques to find patterns in past climate change and to isolate climate signals from noisy data.

James Edward Hansen is an American adjunct professor directing the Program on Climate Science, Awareness and Solutions of the Earth Institute at Columbia University. He is best known for his research in climatology, his 1988 Congressional testimony on climate change that helped raise broad awareness of global warming, and his advocacy of action to avoid dangerous climate change. In recent years, he has become a climate activist to mitigate the effects of global warming, on a few occasions leading to his arrest.

Doomers are people who are extremely pessimistic or fatalistic about global problems such as overpopulation, peak oil, climate change, ecological overshoot, pollution, nuclear weapons, and runaway artificial intelligence. The term, and its associated term doomerism, arose primarily on social media. Some doomers assert that there is a possibility these problems will bring about human extinction.

Joseph J. Romm is an American researcher, author, editor, physicist and climate expert, who advocates reducing greenhouse gas emissions to limit global warming and increasing energy security through energy efficiency and green energy technologies. Romm is a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. In 2009, Rolling Stone magazine named Romm to its list of "100 People Who Are Changing America", and Time magazine named him one of its "Heroes of the Environment (2009)", calling him "The Web's most influential climate-change blogger".

References to climate change in popular culture have existed since the late 20th century and increased in the 21st century. Climate change, its impacts, and related human-environment interactions have been featured in nonfiction books and documentaries, but also literature, film, music, television shows and video games.

Climate change denial is a form of science denial characterized by rejecting, refusing to acknowledge, disputing, or fighting the scientific consensus on climate change. Those promoting denial commonly use rhetorical tactics to give the appearance of a scientific controversy where there is none. Climate change denial includes unreasonable doubts about the extent to which climate change is caused by humans, its effects on nature and human society, and the potential of adaptation to global warming by human actions. To a lesser extent, climate change denial can also be implicit when people accept the science but fail to reconcile it with their belief or action. Several studies have analyzed these positions as forms of denialism, pseudoscience, or propaganda.

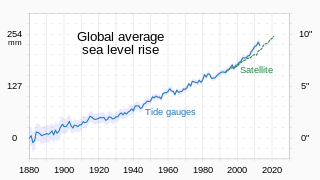

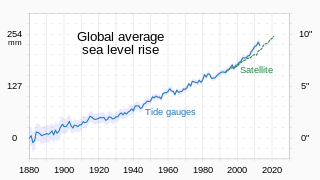

Between 1901 and 2018, the average sea level rose by 15–25 cm (6–10 in), with an increase of 2.3 mm (0.091 in) per year since the 1970s. This was faster than the sea level had ever risen over at least the past 3,000 years. The rate accelerated to 4.62 mm (0.182 in)/yr for the decade 2013–2022. Climate change due to human activities is the main cause. Between 1993 and 2018, melting ice sheets and glaciers accounted for 44% of sea level rise, with another 42% resulting from thermal expansion of water.

The Climatic Research Unit email controversy began in November 2009 with the hacking of a server at the Climatic Research Unit (CRU) at the University of East Anglia (UEA) by an external attacker, copying thousands of emails and computer files to various internet locations several weeks before the Copenhagen Summit on climate change.

Media coverage of climate change has had effects on public opinion on climate change, as it conveys the scientific consensus on climate change that the global temperature has increased in recent decades and that the trend is caused by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases.

Timothy Francis Ball was a British-born Canadian public speaker and writer who was a professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Winnipeg from 1971 until his retirement in 1996. Subsequently Ball became active in promoting rejection of the scientific consensus on global warming, giving public talks and writing opinion pieces and letters to the editor for Canadian newspapers.

Guy R. McPherson is an American scientist, professor emeritus of natural resources and ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Arizona. He is known for inventing and promoting fringe theories such as Near-Term Human Extinction (NTHE), which predicts human extinction by 2026.

From the 1980s to mid 2000s, ExxonMobil was a leader in climate change denial, opposing regulations to curtail global warming. For example, ExxonMobil was a significant influence in preventing ratification of the Kyoto Protocol by the United States. ExxonMobil funded organizations critical of the Kyoto Protocol and seeking to undermine public opinion about the scientific consensus that global warming is caused by the burning of fossil fuels. Of the major oil corporations, ExxonMobil has been the most active in the debate surrounding climate change. According to a 2007 analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists, the company used many of the same strategies, tactics, organizations, and personnel the tobacco industry used in its denials of the link between lung cancer and smoking.

David Wallace-Wells is an American journalist known for his writings on climate change. He wrote the 2017 essay "The Uninhabitable Earth"; the essay was published in New York as a long-form article and was the most-read article in the history of the magazine. Wells later expanded the article into a 2019 book of the same title. At the time, he was the Deputy Editor of New York Magazine and covered the climate crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic extensively. He was hired in March 2022 by The New York Times to write a weekly newsletter and contribute to The New York Times Magazine.

The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming is a 2019 non-fiction book by David Wallace-Wells about the consequences of global warming. It was inspired by his New York magazine article "The Uninhabitable Earth" (2017).

The history of climate change policy and politics refers to the continuing history of political actions, policies, trends, controversies and activist efforts as they pertain to the issue of climate change. Climate change emerged as a political issue in the 1970s, when activist and formal efforts sought to address environmental crises on a global scale. International policy regarding climate change has focused on cooperation and the establishment of international guidelines to address global warming. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is a largely accepted international agreement that has continuously developed to meet new challenges. Domestic policy on climate change has focused on both establishing internal measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and incorporating international guidelines into domestic law.

Climate change and civilizational collapse refers to a hypothetical risk of the impacts of climate change reducing global socioeconomic complexity to the point complex human civilization effectively ends around the world, with humanity reduced to a less developed state. This hypothetical risk is typically associated with the idea of a massive reduction of human population caused by the direct and indirect impacts of climate change, and often, it is also associated with a permanent reduction of the Earth's carrying capacity. Finally, it is sometimes suggested that a civilizational collapse caused by climate change would soon be followed by human extinction.