Related Research Articles

Belfast is the capital city and principal port of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan and connected to the open sea through Belfast Lough and the North Channel. It is the second-largest city on the island of Ireland, with an estimated population of 348,005 in 2022, and a metropolitan area population of 671,559.

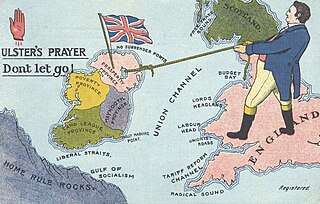

Unionism in Ireland is a political tradition that professes loyalty to the crown of the United Kingdom and to the union it represents with England, Scotland and Wales. The overwhelming sentiment of Ireland's Protestant minority, unionism mobilised in the decades following Catholic Emancipation in 1829 to oppose restoration of a separate Irish parliament. Since Partition in 1921, as Ulster unionism its goal has been to retain Northern Ireland as a devolved region within the United Kingdom and to resist the prospect of an all-Ireland republic. Within the framework of the 1998 Belfast Agreement, which concluded three decades of political violence, unionists have shared office with Irish nationalists in a reformed Northern Ireland Assembly. As of February 2024, they no longer do so as the larger faction: they serve in an executive with an Irish republican First Minister.

Belfast South was a parliamentary constituency in the United Kingdom House of Commons.

The Ulster Unionist Labour Association (UULA) was an association of trade unionists founded by Edward Carson in June 1918, aligned with the Ulster Unionists in Ireland. Members were known as Labour Unionists. In Britain, 1918 and 1919 were marked by intense class conflict. This phenomenon spread to Ireland, the whole of which was part of the United Kingdom at the time. This period also saw a large increase in trade union membership and a series of strikes. These union activities raised fears in a section of the Ulster Unionist leadership, principally Edward Carson and R. Dawson Bates. Carson at this time was president of the British Empire Union, and had been predisposed to amplify the danger of a Bolshevik outbreak in Britain.

The Independent Loyal Orange Institution is an offshoot of the Orange Institution, a Protestant fraternal organisation based in Northern Ireland. Initially pro-labour and supportive of tenant rights and land reform, over time it moved to a more conservative, unionist position.

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants. It also has lodges in England, Scotland, Wales and the Republic of Ireland, as well as in parts of the Commonwealth of Nations and the United States.

Protestant Irish Nationalists are adherents of Protestantism in Ireland who also support Irish nationalism. Protestants have played a large role in the development of Irish nationalism since the eighteenth century, despite most Irish nationalists historically being from the Irish Catholic majority, as well as most Irish Protestants usually tending toward unionism in Ireland. Protestant nationalists have consistently been influential supporters and leaders of various movements for the political independence of Ireland from Great Britain. Historically, these movements ranged from supporting the legislative independence of the Parliament of the Kingdom of Ireland, to a form of home rule within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, to complete independence in an Irish Republic and a United Ireland.

Henry Cassidy Midgley, PC (NI), known as Harry Midgley was a prominent trade-unionist and politician in Northern Ireland. Born to a working-class Protestant family in Tiger's Bay, north Belfast, he followed his father into the shipyard. After serving on the Western Front in the Great War, he became an official in a textile workers union and a leading light in the Belfast Labour Party (BLP). He represented the party's efforts in the early 1920s to provide a left opposition to the Unionist government of the new Northern Ireland while remaining non-committal on the divisive question of Irish partition.

William McMullen was an Irish trade unionist and politician. A member of the Labour movement, McMullen primary work was a trade unionist, but he was also a successful politician who secured office in the Parliament of Northern Ireland. Despite coming from a Presbyterian family, McMullen was also an avowed Irish republican, bitterly opposing the partition of Ireland in the 1920s and joining the Republican Congress in the 1930s. In the 1940s McMullen became the leader of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union and in the 1950s, he became a member of the Irish senate.

Victor Halley was an Irish trade unionist and socialist in Northern Ireland, who identified the cause of labour with the achievement of an all-Ireland republic.

William Johnston was an Irish Orangeman, unionist and Member of Parliament for Belfast, distinguished by his independent working-class following and commitment to reform. He first entered the United Kingdom Parliament as an Irish Conservative in 1868, celebrated for having broken a standing ban on Orange Order processions and as the nominee of an association of "Protestant Workers". At Westminster, Johnston supported the secret ballot; the accommodation of trade unions and strike action; land reform; and woman's suffrage. He was succeeded in 1902 as the MP for South Belfast, by Thomas Sloan, similarly supported by loyalist workers in opposition to the official unionist candidates favoured by their employers.

The Loyal Orange Institution, better known as the Orange Order, is a Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland. It has been a strong supporter of Irish unionism and has had close links with the Ulster Unionist Party, which governed Northern Ireland from 1922 to 1972. The Orange Order has lodges throughout Ireland, although it is strongest in the North. There are also branches throughout the Commonwealth, and in the United States. In the 20th century, the organisation went into sharp decline outside Northern Ireland and County Donegal. McGarry, John; O'Leary, Brendan (1995). Explaining Northern Ireland: Broken Images. Blackwell Publishers. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-631-18349-5.; The Orange marches</ref> The Order has a substantial fraternal and benevolent component.

Thomas Henry Sloan (1870–1941) was an Irish unionist and co-founder of the Independent Orange Order (IOO). The choice of a loyalist workers association over the official Conservative Unionist nominee, he represented the Belfast South constituency as an Independent Unionist at the Westminster parliament from 1902 to 1910. He and members of the IOO supported workers in the Belfast Lockout of 1907.

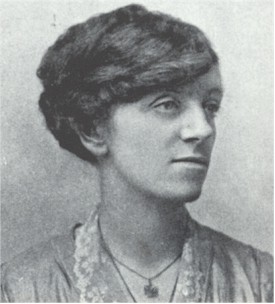

Maria Winifred "Winnie" Carney, was an Irish republican, a participant in the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin, and in Belfast—as a trade union secretary, women's suffragist, and socialist party member—a lifelong social and political activist. In March 2024, a statue to her was unveiled on the grounds of Belfast City Hall.

The Belfast Protestant Association was a populist evangelical political movement in the early 20th-century.

The 1886 Belfast riots were a series of intense riots that occurred in Belfast, Ireland, during the summer and autumn of 1886.

The Belfast Dock strike or Belfast lockout took place in Belfast, Ireland from 26 April to 28 August 1907. The strike was called by Liverpool-born trade union leader James Larkin who had successfully organised the dock workers to join the National Union of Dock Labourers (NUDL). The dockers, both Protestant and Catholic, had gone on strike after their demand for union recognition was refused. They were soon joined by carters, shipyard workers, sailors, firemen, boilermakers, coal heavers, transport workers, and women from the city's largest tobacco factory. Most of the dock labourers were employed by powerful tobacco magnate Thomas Gallaher, chairman of the Belfast Steamship Company and owner of Gallaher's Tobacco Factory.

The 1902 Belfast South by-election was held on 18 August 1902 after the death of the Irish Unionist Party MP William Johnston. It was won by the Independent Unionist candidate Thomas Henry Sloan.

Robert Lindsay Crawford (1868–1945) was an Irish Protestant politician and journalist who shifted in his loyalties from Unionism and the Orange Order to the Irish Free State. He was a co-founder of the Independent Orange Order through which he hoped to promote Irish reconciliation and democracy. Later he became a committed Irish nationalist mobilizing support in Canada for Irish self-determination and serving the new Irish state as its trade representative and consul in New York City.

This article is intended to show a timeline of the history of Belfast, Northern Ireland, up to the present day.

References

- ↑ James Quinn. "Carnduff, Thomas". Dictionary of Irish Biography. (Eds.)James Mcguire, James Quinn. Cambridge, United Kingdom:Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- ↑ Boyle, J. W. (1962–1963). "The Belfast Protestant Association and Independent Orange Order". Irish Historical Studies. 13: 117–152. doi:10.1017/S0021121400008518. S2CID 163283785.

- 1 2 Courtney, Roger (2013). Dissenting Voices: Rediscovering the Irish Progressive Presbyterian Tradition. Belfast: Ulster Historical Society. pp. 286–287. ISBN 9781909556065.

- ↑ Smyth, Denis (1991). "Thomas Carnduff". In Hall, Michael (ed.). Belfast, Belfast, Volume 1. Belfast: Belfast History Workshop. p. 36.

- 1 2 3 4 Devlin, Patrick. "Thomas Carnduff (1886 - 1956): Poet and playwright -'The Shipyard Poet'. The Dictionary of Ulster Biography". www.newulsterbiography.co.uk. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- 1 2 Maxwell, Nick (2018). "Inventing the Myth: Political Passions and the Ulster Protestant Imagination". History Ireland. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ↑ Parr, Conal (12 January 2021). "Thomas Carnduff — the shipyard worker, Orangeman and poet who could be a face for Northern Ireland to mark its centenary". News Letter.

- ↑ Production, March 1991 (9 May 2023). "The Writings of Thomas Carnduff". Tinderbox Theatre Company. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Madden, Robert (1900). Antrim and Down in '98 : The Lives of Henry Joy m'Cracken, James Hope, William Putnam m'Cabe, Rev. James Porter, Henry Munro. Glasgow: Cameron, Ferguson & Co. p. 108.

- ↑ Longley, Edna (1994). The Living Stream: Literature and Revisionism in Ireland. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Bloodaxe Books. p. 124. ISBN 1852242175.

- ↑ Fischer, William (2019). "Thomas Carnduff". Ulster History Circle. Retrieved 18 June 2023.