Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus Nicotiana of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the chief commercial crop is N. tabacum. The more potent variant N. rustica is also used in some countries.

The Atsugewi are Native Americans residing in northeastern California, United States. Their traditional lands are near Mount Shasta, specifically the Pit River drainage on Burney, Hat, and Dixie Valley or Horse Creeks. They are closely related to the Achomawi and consisted of two groups. The Atsugé traditionally are from the Hat Creek area, and the Apwaruge are from the Dixie Valley. They lived to the south of the Achomawi.

Yurok is an Algic language. It is the traditional language of the Yurok people of Del Norte County and Humboldt County on the far north coast of California, most of whom now speak English. The last known native speaker, Archie Thompson, died in 2013. As of 2012, Yurok language classes were taught to high school students, and other revitalization efforts were expected to increase the population of speakers.

The Hupa are a Native American people of the Athabaskan-speaking ethnolinguistic group in northwestern California. Their endonym is dining’xine:wh for Hupa-language speakers in general, and na:tinixwe for residents of Hoopa Valley, also spelled Natinook-wa, meaning "People of the Place Where the Trails Return". The Karuk name for them is Kishákeevar / Kishakeevra. The majority of the tribe is enrolled in the federally recognized Hoopa Valley Tribe.

The Wiyot are an indigenous people of California living near Humboldt Bay, California and a small surrounding area. They are culturally similar to the Yurok people. They called themselves simply Ku'wil, meaning "the People". Today, there are approximately 450 Wiyot people. They are enrolled in several federally recognized tribes, such as the Wiyot Tribe, Bear River Band of the Rohnerville Rancheria, Blue Lake Rancheria, and the Cher-Ae Heights Indian Community of the Trinidad Rancheria.

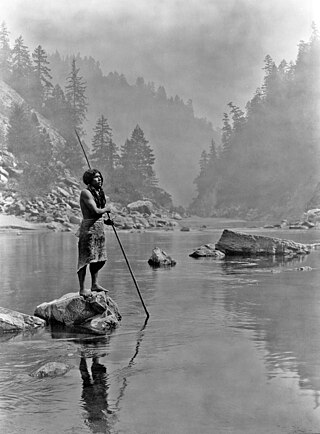

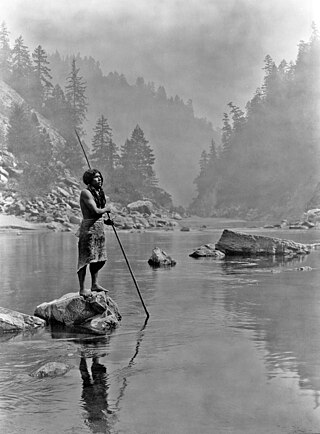

The Yurok people are an Algic-speaking Indigenous people of California that has existed along the Hehlkeek 'We-Roy or "Health-kick-wer-roy" and on the Pacific coast, from Trinidad south of the river’s mouth almost to Crescent City along the north coast.

A smoking pipe is used to taste the smoke of a burning substance; most common is a tobacco pipe. Pipes are commonly made from briar, heather, corncob, meerschaum, clay, cherry, glass, porcelain, ebonite and acrylic.

Religious views on smoking vary widely. Indigenous peoples of the Americas have traditionally used tobacco for religious purposes, while Abrahamic and other religions have only been introduced to the practice in recent times due to the European colonization of the Americas in the 16th century.

The history of commercial tobacco production in the United States dates back to the 17th century when the first commercial crop was planted. The industry originated in the production of tobacco for British pipes and snuff. See Tobacco in the American colonies. In late 18th century there was an increase in demand for tobacco in the United States, where the demand for tobacco in the form of cigars and chewing tobacco increased. In the late 19th century production shifted to the manufactured cigarette.

Tobacco was long used in the early Americas. The arrival of Spain introduced tobacco to the Europeans, and it became a lucrative, heavily traded commodity to support the popular habit of smoking. Following the Industrial Revolution, cigarettes became hugely popular worldwide. In the mid-20th century, medical research demonstrated severe negative health effects of tobacco smoking including lung and throat cancer, which led to governments adopting policies to force a sharp decline in tobacco use.

Che-na-wah Weitch-ah-wah (1856-1932), commonly known by her English name Lucy Thompson, was a Yurok author, best known for her book To the American Indian: Reminiscences of a Yurok Woman. Written in 1916, the book is intended to preserve her people's stories. The book received the American Book Award decades later in 1992. Thompson was born in the Klamath River village of Pecwan. Outside the book she is known to have come from "Yurok aristocracy" and to be married to a Euro-American man named Milton "Jim" Thompson. She intended to tell the stories of her people that were not being told by others, and to make others better understand her people and perspective, although she also criticized whites for practices like overfishing. Thompson expressed that violence towards indigenous Californians were deliberate acts of genocide and she expressed concern for the continued stewardship of Klamath River salmon.

Klamath Glen is an unincorporated community in Del Norte County, California. It is located on the Klamath River 5 miles (8 km) from its mouth, at an elevation of 46 feet.

Oketo is a former Yurok settlement in Humboldt County, California, but experts differ on what the names were of the settlement itself and of the nearby waterway now called Big Lagoon. Yurok author Chenahwah Weitchahwah used the name Ah-ca-tah when mentioning the location of a religious practice but was unclear whether she was naming the village or lagoon. Peter Palmquist placed the village at the south shore of the lagoon. A. L. Kroeber said the village was called Opyuweg, mapping it in more detail. T. T. Waterman said the lagoon was named Oketo and pinpointed the village most precisely as Opyuweg, setting it west of a southern promontory of the lagoon and of a settlement called piNpa. Coastal Yuroks call themselves Ner-'er-'ner or Ner-er-ner and upriver Yuroks call themselves Pue-lik-lo' or Polikla. In his notes, C. H. Merriman recorded that Oketo was the name the Polikla or Pue-lik-lo' used for a Ner-er-ner village at Big Lagoon.

Slavery among Native Americans in the United States includes slavery by and enslavement of Native Americans roughly within what is currently the United States of America.

Depictions of tobacco smoking in art date back at least to the pre-Columbian Maya civilization, where smoking had religious significance. The motif occurred frequently in painting of the 17th-century Dutch Golden Age, in which people of lower social class were often shown smoking pipes. In European art of the 18th and 19th centuries, the social location of people – largely men – shown as smoking tended to vary, but the stigma attached to women who adopted the habit was reflected in some artworks. Art of the 20th century often used the cigar as a status symbol, and parodied images from tobacco advertising, especially of women. Developing health concerns around tobacco smoking also influenced its artistic representation.

During and after the European colonization of the Americas, European settlers practiced widespread enslavement of Indigenous peoples. In the 15th century, the Spanish introduced chattel slavery through warfare and the cooption of existing systems. A number of other European powers followed suit, and from the 15th through the 19th centuries, between two and five million Indigenous people were enslaved, which had a devastating impact on many Indigenous societies, contributing to the overwhelming population decline of Indigenous peoples in the Americas.

A ceremonial pipe is a particular type of smoking pipe, used by a number of cultures of the indigenous peoples of the Americas in their sacred ceremonies. Traditionally they are used to offer prayers in a religious ceremony, to make a ceremonial commitment, or to seal a covenant or treaty. The pipe ceremony may be a component of a larger ceremony, or held as a sacred ceremony in and of itself. Indigenous peoples of the Americas who use ceremonial pipes have names for them in each culture's Indigenous language. Not all cultures have pipe traditions, and there is no single word for all ceremonial pipes across the hundreds of diverse Native American languages.

Kinnikinnick is a Native American and First Nations herbal smoking mixture, made from a traditional combination of leaves or barks. Recipes for the mixture vary, as do the uses, from social, to spiritual to medicinal.

Native American cultures across the 574 current federally recognized tribes in the United States, can vary considerably by language, beliefs, customs, practices, laws, art forms, traditional clothing, and other facets of culture. Yet along with this diversity, there are certain elements which are encountered frequently and shared by many tribal nations.

The ownership of enslaved people by indigenous peoples of the Americas extended throughout the colonial period up to the abolition of slavery. Indigenous people enslaved Amerindians, Africans, and—occasionally—Europeans.