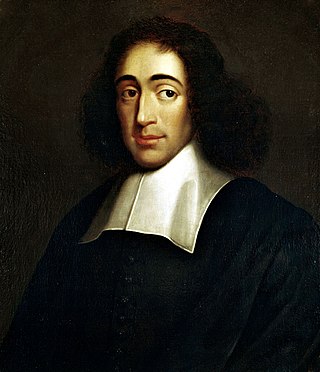

Baruch (de) Spinoza, also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin. A forerunner of the Age of Enlightenment, Spinoza significantly influenced modern biblical criticism, 17th-century rationalism, and Dutch intellectual culture, establishing himself as one of the most important and radical philosophers of the early modern period. Influenced by Stoicism, Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, Ibn Tufayl, and heterodox Christians, Spinoza was a leading philosopher of the Dutch Golden Age.

Bernardino Ochino (1487–1564) was an Italian, who was raised a Roman Catholic and later turned to Protestantism and became a Protestant reformer.

René Descartes was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathematics was paramount to his method of inquiry, and he connected the previously separate fields of geometry and algebra into analytic geometry. Descartes spent much of his working life in the Dutch Republic, initially serving the Dutch States Army, and later becoming a central intellectual of the Dutch Golden Age. Although he served a Protestant state and was later counted as a deist by critics, Descartes was Roman Catholic.

François-Marie Arouet, known by his nom de plumeM. de Voltaire, was a French Enlightenment writer, philosopher (philosophe), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit and his criticism of Christianity and of slavery, Voltaire was an advocate of freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and separation of church and state.

Étienne Bonnot de Condillac was a French philosopher, epistemologist, and Catholic priest, who studied in such areas as psychology and the philosophy of the mind.

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1770.

Roy Sydney Porter was a British historian known for his work on the history of medicine. He retired in 2001 as the director of the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine at University College London (UCL).

Richard Henry Popkin was an American academic philosopher who specialized in the history of enlightenment philosophy and early modern anti-dogmatism. His 1960 work The History of Scepticism from Erasmus to Descartes introduced one previously unrecognized influence on Western thought in the seventeenth century, the Pyrrhonian Scepticism of Sextus Empiricus. Popkin also was an internationally acclaimed scholar on Christian millenarianism and Jewish messianism.

Jonathan Irvine Israel is a British historian specialising in Dutch history, the Age of Enlightenment, Spinoza's Philosophy and European Jews. Israel was appointed as Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the School of Historical Studies at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, New Jersey, in January 2001 and retired in July 2016. He was previously Professor of Dutch History and Institutions at the University College London.

Bernard Nieuwentijt, Nieuwentijdt, or Nieuwentyt was a Dutch philosopher, mathematician, physician, magistrate, mayor, and theologian.

Neostoicism was a philosophical movement that arose in the late 16th century from the works of Justus Lipsius, and sought to combine the beliefs of Stoicism and Christianity. Lipsius was Flemish and a Renaissance humanist. The movement took on the nature of religious syncretism, although modern scholarship does not consider that it resulted in a successful synthesis. The name "neostoicism" is attributed to two Roman Catholic authors, Léontine Zanta and Julien-Eymard d'Angers.

Adriaan Koerbagh was a Dutch physician, scholar, and writer who was a critic of religion and conventional morality. He was in the circle of supporters of Baruch Spinoza.

Atheism, as defined by the entry in Diderot and d'Alembert's Encyclopédie, is "the opinion of those who deny the existence of a God in the world. The simple ignorance of God doesn't constitute atheism. To be charged with the odious title of atheism one must have the notion of God and reject it." In the period of the Enlightenment, avowed and open atheism was made possible by the advance of religious toleration, but was also far from encouraged.

Lodewijk Meyer was a Dutch physician, classical scholar, translator, lexicographer, and playwright. He was a radical intellectual and one of the more prominent members of the circle around the philosopher Benedictus de Spinoza.

This is a timeline of philosophy in the 17th century.

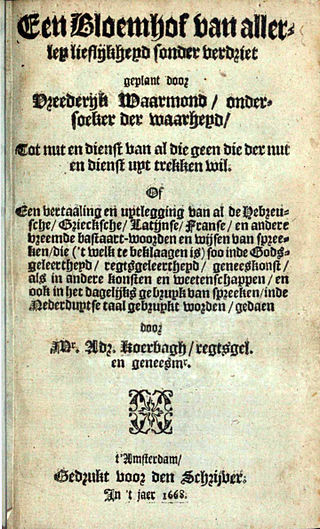

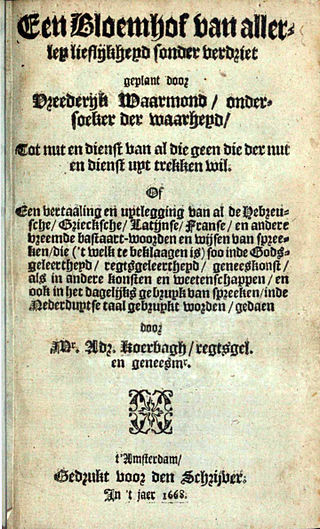

Een Bloemhof is a dictionary published in 1668 and written by Adriaan Koerbagh under his own name. Its full title was Een Bloemhof van allerley Lieflijkheyd sonder verdriet. The book sparked controversy in Amsterdam because of its articles defining political and religious terms, even though they comprise only a small portion of the overall dictionary. The book also offers laymen explanations for technical jargon and foreign terms, covering topics such as medicine and law.

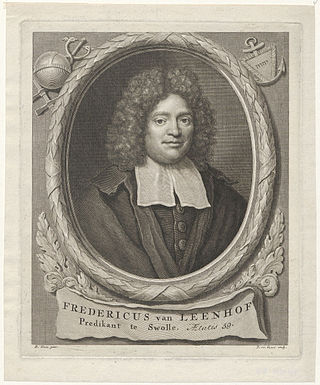

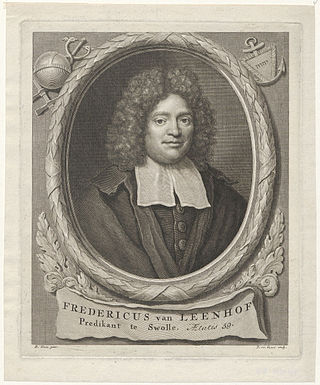

Frederik van Leenhof was a Dutch pastor and philosopher active in Zwolle, who caused an international controversy because of his Spinozist work Heaven on Earth (1703). This controversy is extensively discussed in Jonathan Israel's 2001 book Radical Enlightenment.

Hendrik Wyermars was a Dutch radical Enlightenment thinker from Amsterdam who in 1710 published a philosophical book defending the eternity of the world and rejecting the literal version of the Creation story from the Book of Genesis. For contradicting fundamental Christian doctrine the book was condemned by the local church authorities and Wyermars was subsequently jailed for 15 years in the Amsterdam Rasphuis. He was considered an adherent of Spinozism, proclaiming atheist and materialist views.

Jean-Maximilien Lucas was a French bookseller and publisher, resident in the Netherlands from around 1667. He is now known as the first biographer of Baruch Spinoza.

Discourses Concerning Government is a political work published in 1698, and based on a manuscript written in the early 1680s by the English Whig activist Algernon Sidney who was executed on a treason charge in 1683. It is one of the treatises on governance produced by the Exclusion Crisis of the last years of the reign of Charles II of England. Modern scholarship regards the 1698 book as "fairly close" to Sidney's manuscript. According to Christopher Hill, it "handed on many of the political ideas of the English revolutionaries to eighteen-century Whigs, American and French republicans."