This article possibly contains original research .(February 2021) |

Troels Engberg Pedersen is a Pauline theologian, author, and professor of New Testament exegesis at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark. [1]

This article possibly contains original research .(February 2021) |

Troels Engberg Pedersen is a Pauline theologian, author, and professor of New Testament exegesis at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark. [1]

Dr. Engberg-Pedersen completed his Undergraduate studies in Classics at University of Copenhagen, then went on to study ancient and modern philosophy at University of Oxford from 1974–76, where he was promoted Doctorate of Philosophy. His doctoral thesis, entitled "Aristotle's Theory of Moral Insight,” (1983), was published through Oxford University Press. Engberg-Pedersen's was also promoted Doctorate of Theology. His doctoral studies mark the beginning of his exploration into the influence of Stoicism, on early Christianity, particularly as it relates to the scriptural letters of St.Paul the Apostle.

For approximately 25 years, Pedersen has focused his attentions on the writings of Paul the Apostle and on exploring how the structure and content of the Pauline epistles align with themes which are present in Stoic philosophy of the Hellenistic Period. When set in conjunction with Paul's identity as a Greco-Roman Jew, the implications of Paul's letters standout as a demonstration of how the early Christian church community developed in light of the Greco-Roman world which surrounded it.

Within the Hellenistic Period, the social structure was primarily hierarchical in the Roman Empire. Roman aristocrats were situated at the top of a social pyramid while slaves were the lowest of all society. Unless a generous patron could intercede and assist in facilitating limited mobility of his or her client, the hierarchy stood strong; within smaller groups in Hellenistic culture, such as a family scenario and guilds, this kind of structure was established, as well. [2] As it was laid out in Greek classical thought, there was opportunity for members of society to enter into friendships, based on equality of status, which was typically only achieved by members of the aristocracy, where each party shares all things in common. [3] How one interacted with superiors, equals, and inferiors determined a person's status within this social system. Engberg-Pedersen draws from this background of social relationship within the Roman Empire during the Hellenistic period in order to show Paul's approach to early Christianity:evidence of friendship motifs were very present within the letter-writing practices of that period and can be seen very plainly, particularly in Paul's letters to the Philippians.

Within Paul's own understanding of hierarchy between Heaven and Earth, he sees God as being situated within the highest place, with Christ right below. Only just underneath Christ's ranking, Paul sees himself, followed by his co-workers, and finally includes those in the faith communities and those outside of the Christian circle. Engberg-Pedersen introduces this concept as being a “notion of subordination…”. While emphasizing a tenor of friendship within his letters, it should also be recognized that there is an authority within the messages, due to Paul's protectiveness over of his apostleship, based on his concept of hierarchy that he has in place for himself, he also has to maneuver his theological principles in response to the influences of the hierarchy at work in the sociopolitical system he sees around him. Political celebrations and expectations from the Empire, inclusive of those in the early Christian communities Paul founded, proved to be problematic for the members and followers. Maintaining a Christian lifestyle while navigating the sociopolitical factors was the cause of quite a bit of detailed instruction from Paul in some of his letters. Within his written responses and advisement to individual Christian communities, Engberg-Pedersen makes claims that Paul draws from common understandings of societal practices of his time, yet strives to make them applicable to new context for his followers.

Engberg-Pedersen draws from the scholarship done by John T. Fitzgerald when discussing how Paul uses the social practice of forgiveness and atonement to illustrate Christian practices. Fitzgerald, in Paul and Paradigm Shifts: Reconciliation and Its Linkage Group [4] discusses that in the Greco-Roman world, it was left to a guilty person to appeal to the goodwill of the person that he or she offended, with the hope that the offended person would choose to forgive the wrong. This understanding of forgiveness was fairly dichotomized between how one forgives within a public, social structure and how a person approached a more religious form of atonement. The perspective of Paul and his advice to quarreling communities take on a deeper implication for relationship within members of the church in seeing him interweave these two concepts into one; through his use of the rhetoric of the time, counterbalanced by his own experience of mercy from God in his own conversion, Paul takes the societal attitude toward reconciliation and makes it into a spiritual consideration of forgiveness: God is the initiator of the forgiveness, even when we are sinful. Even though we may offend God, He offers an appeal to reconcile us to himself. This paradigm shift is particularly present within Paul's second letter to the Corinthians (see [2 Corinthians 5:20-21] [5] ), where Paul implores the Christian community to make reparations in their relationships with each other through illustrating Christ's death on the cross. Troels Engberg-Pedersen complements Fitzgerald's discussion of Christian forgiveness as a means of illustrating how Paul's writings emphasize the link between relationship with God and human agency.

Within his text, Cosmology and the Self in the Apostle Paul, Troel Engberg-Pedersen illustrates this link between human and divine through a concept that he creates, consisting of an “I”-“X”-“S”, where “I” designates the individual self, “X” is Christ and “S” is the social/shared pole [6] In this figure, he shows that in the letters of Paul, the apostle describes a way of self-understanding in which the individual intentionally directs everything he or she toward God and Christ (e.g. Gal 2:20, [7]

Pedersen shows that this directed-ness toward God and Christ manifests itself in becoming other-centered through this relationship. Through individual awareness and a recognition of connection with Father and Son, resulting in the building up the broader community, it is easy to see that this interaction between the human and divine illustrates the foundational tenets upon which the modern structure of church had been established. Throughout the letters, even though it is not with any frequency, Paul is shown to draw upon his own self-awareness and experience of Christ in order to demonstrate how Christians should humble themselves before God in order to serve others through their commitment to Christ. For instance, Paul uses himself as an example of in his Letter to the Philippians:

Within the Stoic tradition, Engberg-Pedersen describes an ideal of society conceived by founder Zeno, which prescribes a political system established on the tenets of homonoia, philia and Eleutheria, rather than a broken down educational system which causes hostility and division. Chrysippus, Stoicism's second founder, believed the ideal society to be that which was made up of people who were morally good, but also had a healthy citizenship through governance. [9]

In his limited rhetorical training, this understanding of moral citizenship as described in Stoicism influences Paul's writings, and reflect a spirit of what Engberg-Pedersen describes as koinonia, or a sense of communion amongst members of the same society. Within this communion as a family of faith, can each member be held accountable for upholding belief and virtue in Christ, and not succumbing to vice (Phil 4:8-9 [10] ). It is the very same spirit of communion that he describes in his letter to Philippians which drives Paul to view the corporal Christian church as superseding the faith of the individual person. [11] It is this philosophical starting point that guides Paul's emphasis on “citizenship of Heaven” that he alludes to in Philippians 3:15-20, which says "Let us, then, who are ‘perfectly mature’ adopt this attitude. And if you have a different attitude, this too God will reveal to you. Only, with regard to what we have attained, continue on the same course...but our citizenship is in heaven and from it we also await a savior, the Lord Jesus Christ.” [12]

Engberg-Pedersen illustrates this “I”-“X”-“S” relationship between the human person, the divine and the human family, in the same spirit that Paul strives to help his communities in re-assessing their status as Christians in reference to where they situate themselves within the larger Hellenistic society. Within Greek philosophy, a movement that Paul describes toward achieving full potential and personhood is referred to as the telos. However, in his book, Cosmology and the Self, Troels Engberg-Pedersen refers to this concept of true human self within a stoic understanding, as “prohairesis,” where he seeks to outline it as it relates to the being of a Christian. Engberg makes the distinction that in looking at a person's capacity for decision-making, but also a sense of ‘self’ that recognizes commonality with fellow human beings, and a sense of other-centeredness:

Within Troels Engberg-Pedersen's scholarship, he describes the sensibilities and social structures within a Hellenistic society, in order that he might further illustrate the significance of the Apostle Paul's writings as a continuation of spiritual understanding of the faith community, and demonstrate the influences of the period of Paul's writings. In doing so, Engberg-Pedersen gives us a glimpse of what implications Paul's society provides for the Church in current history. The influences of the social surroundings within Greco-Roman world heavily influences his letters and provides modern scholarship with significant considerations within the structure we see within the Church today.

Through an understanding of the situational nature of Paul's writings within his historical context, there can be a gain of better appreciation for the deeper themes that still have relevance for the mission of the Christian church in a 21st-century context. Above all, Engberg-Pedersen, while considering the historical implications of Paul's work within his letters to the early Christian communities, advocates that modern Christians follow in Paul's footsteps by focusing on a missionary vision for living out their encounters with Christ and the pneuma. [14] In remaining in communion with the spirit and Christ Jesus, and striving to proclaim the gospel message, Pedersen also believes that it is important to keep a healthy, realistic perspective regarding a person's humanity. In the way that he interprets the Letters of St. Paul, Troels Engberg-Pedersen expresses that in Paul's call to bring the gospel to the Gentiles, Paul sets forth a model of discipleship that spans beyond his place in history, but rather provides a structure for Christianity which will continue to guide the Church into the future.

The Acts of the Apostles is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its message to the Roman Empire.

The Epistle to the Philippians is a Pauline epistle of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The epistle is attributed to Paul the Apostle and Timothy is named with him as co-author or co-sender. The letter is addressed to the Christian church in Philippi. Paul, Timothy, Silas first visited Philippi in Greece (Macedonia) during Paul's second missionary journey from Antioch, which occurred between approximately 50 and 52 AD. In the account of his visit in the Acts of the Apostles, Paul and Silas are accused of "disturbing the city".

The Epistle to Philemon is one of the books of the Christian New Testament. It is a prison letter, authored by Paul the Apostle, to Philemon, a leader in the Colossian church. It deals with the themes of forgiveness and reconciliation. Paul does not identify himself as an apostle with authority, but as "a prisoner of Jesus Christ", calling Timothy "our brother", and addressing Philemon as "fellow labourer" and "brother". Onesimus, a slave that had departed from his master Philemon, was returning with this epistle wherein Paul asked Philemon to receive him as a "brother beloved".

The Gospel of Luke is the third of the New Testament's four canonical Gospels. It tells of the origins, birth, ministry, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus. Together with the Acts of the Apostles, it makes up a two-volume work which scholars call Luke–Acts, accounting for 27.5% of the New Testament. The combined work divides the history of first-century Christianity into three stages, with the gospel making up the first two of these – the life of Jesus the messiah (Christ) from his birth to the beginning of his mission in the meeting with John the Baptist, followed by his ministry with events such as the Sermon on the Plain and its Beatitudes, and his Passion, death, and resurrection.

The Holy Spirit, otherwise known as the Holy Ghost, is a concept within the Abrahamic religions. In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is understood as the divine quality or force of God manifesting in the world, particularly in acts of prophecy, creation and guidance. In Nicene Christianity, this conception expanded in meaning to represent the third person of the Trinity, co-equal and co-eternal with God the Father and God the Son. In Islam, the Holy Spirit acts as an agent of divine action or communication. In the Baha’i Faith, the Holy Spirit is seen as the intermediary between God and man and "the outpouring grace of God and the effulgent rays that emanate from His Manifestation".

Paul also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Christian apostle who spread the teachings of Jesus in the first-century world. For his contributions towards the New Testament, he is generally regarded as one of the most important figures of the Apostolic Age, and he also founded several Christian communities in Asia Minor and Europe from the mid-40s to the mid-50s AD.

An epistle is a writing directed or sent to a person or group of people, usually an elegant and formal didactic letter. The epistle genre of letter-writing was common in ancient Egypt as part of the scribal-school writing curriculum. The letters in the New Testament from Apostles to Christians are usually referred to as epistles. Those traditionally attributed to Paul are known as Pauline epistles and the others as catholic epistles.

Christianity and Hellenistic philosophies experienced complex interactions during the first to the fourth centuries.

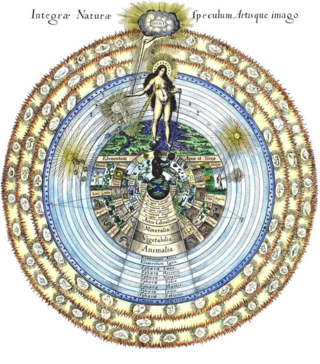

The concept of the anima mundi (Latin), world soul, or soul of the world posits an intrinsic connection between all living beings, suggesting that the world is animated by a soul much like the human body. Rooted in ancient Greek and Roman philosophy, the idea holds that the world soul infuses the cosmos with life and intelligence. This notion has been influential across various systems of thought, including Stoicism, Gnosticism, Neoplatonism, and Hermeticism, shaping metaphysical and cosmological frameworks throughout history.

The Correspondence ofPaul and Seneca, also known as the Letters of Paul and Seneca or Epistle to Seneca the Younger, is a collection of letters claiming to be between Paul the Apostle and Seneca the Younger. There are 8 epistles from Seneca, and 6 replies from Paul. They were purportedly authored from 58–64 CE during the reign of Roman Emperor Nero, but appear to have actually been written in the middle of the fourth century. Until the Renaissance, the epistles were seen as genuine, but scholars began to critically examine them in the 15th century, and today they are held to be inauthentic forgeries.

Palingenesis is a concept of rebirth or re-creation, used in various contexts in philosophy, theology, politics, and biology. Its meaning stems from Greek palin, meaning 'again', and genesis, meaning 'birth'.

Koinonia, communion, or fellowship in Christianity is the bond uniting Christians as individuals and groups with each other and with Jesus Christ. It refers to group cohesiveness among Christians.

God-fearers or God-worshippers were a numerous class of Gentile sympathizers to Hellenistic Judaism that existed in the Greco-Roman world, which observed certain Jewish religious rites and traditions without becoming full converts to Judaism. The concept has precedents in the proselytes of the Hebrew Bible.

Pneuma is an ancient Greek word for "breath", and in a religious context for "spirit". It has various technical meanings for medical writers and philosophers of classical antiquity, particularly in regard to physiology, and is also used in Greek translations of ruachרוח in the Hebrew Bible, and in the Greek New Testament.

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. The Stoics believed that the practice of virtue is enough to achieve eudaimonia: a well-lived life. The Stoics identified the path to achieving it with a life spent practicing the four cardinal virtues in everyday life — prudence, fortitude, temperance, and justice — as well as living in accordance with nature. It was founded in the ancient Agora of Athens by Zeno of Citium around 300 BCE.

Since the 1970s, scholars have sought to place Paul the Apostle within his historical context in Second Temple Judaism. Paul's relationship to Judaism involves topics including the status of Israel's covenant with God and the role of works as a means to either gain or keep the covenant.

The relationship between Paul the Apostle and women is an important element in the theological debate about Christianity and women because Paul was the first writer to give ecclesiastical directives about the role of women in the Church. However, there are arguments that some of these writings are post-Pauline interpolations.

The Last Adam, also given as the Final Adam or the UltimateAdam, is a title given to Jesus in the New Testament. Similar titles that also refer to Jesus include Second Adam and New Adam.

The New Testament Household Codes, also known as New Testament Domestic Codes, consist of instructions in New Testament writings associated with the apostles Paul and Peter to pairs of Christian people within the structure of a typical Roman household. The main foci of the Household Codes are upon husband/wife, parent (father)/child, and master/slave relationships. Some argue that The Codes were developed to urge the new first century Christians to comply with the non-negotiable requirements of Roman Patria Potestas law, and to meet the needs for order within the fledgling churches. The two main texts that address these relationships and duties are Ephesians 5:22–6:9 and Colossians 3:18–4:1. An underlying Household Code is also reflected in 1 Timothy 2:1ff., 8ff.; 3:1ff., 8ff.; 5:17ff.; 6:1f.; Titus 2:1–10 and 1 Peter 2:13–3:7. Historically, proof texts from the New Testament Household Codes—from the first century to the present day—have been used to define a married Christian woman's role in relation to her husband, and to disqualify women from primary ministry positions in Christian churches.

Seneca the Younger's Letter 47 of his Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium, sometimes known as On Master and Slave or On Slavery, is an essayistic look at dehumanization in the context of slavery in ancient Rome. It was a criticism of aspects of Roman slavery, without outright opposition to it, and had a favorable later reception by Enlightenment philosophers and subsequently the 19th century abolitionist movement. Conversely, the text has also been seen as a proslavery apologia, as well as in the light of the Stoic philosophical idea that "all men are slaves".