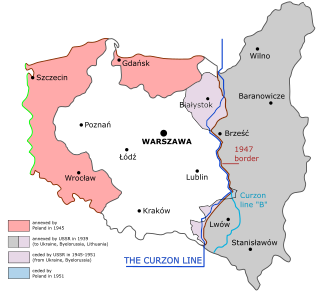

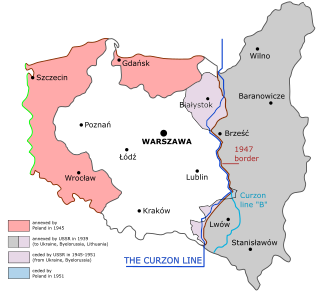

Eastern Borderlands or simply Borderlands was a term coined for the eastern part of the Second Polish Republic during the interwar period (1918–1939). Largely agricultural and extensively multi-ethnic with a Polish minority, it amounted to nearly half of the territory of interwar Poland. Historically situated in the eastern Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, following the 18th-century foreign partitions it was divided between the Empires of Russia and Austria-Hungary, and ceded to Poland in 1921 after the Treaty of Riga. As a result of the post-World War II border changes, all of the territory was ceded to the USSR, and none of it is in modern Poland.

Andrzej Sakson is a Polish sociologist and historian. Since 2004 he has been the director of the Western Institute in Poznań.

Polonophobia, also referred to as anti-Polonism or anti-Polish sentiment are terms for negative attitudes, prejudices, and actions against Poles as an ethnic group, Poland as their country, and their culture. These include ethnic prejudice against Poles and persons of Polish descent, other forms of discrimination, and mistreatment of Poles and the Polish diaspora.

Marek Jan Chodakiewicz is a Polish-American historian specializing in Central European history of the 19th and 20th centuries. He teaches at the Patrick Henry College and at the Institute of World Politics. He has been described as conservative and nationalistic, and his attitude towards minorities has been widely criticized.

Robert Witold Makłowicz is a Polish food critic, journalist, historian and television personality, notable as a promoter of the Polish cuisine and slow food. He is best known for his series of culinary TV programs Makłowicz w podróży.

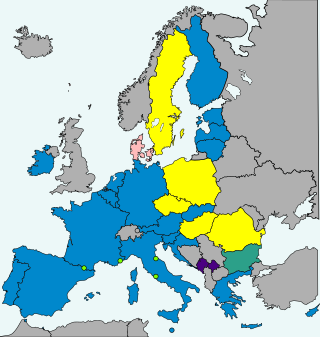

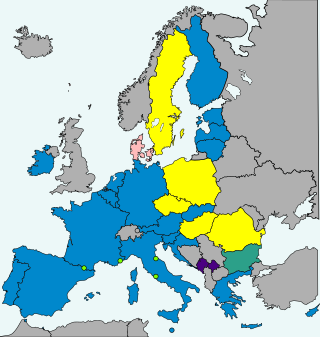

Poland does not use the euro as its currency. However, under the terms of their Treaty of Accession with the European Union, all new Member States "shall participate in the Economic and Monetary Union from the date of accession as a Member State with a derogation", which means that Poland is obliged to eventually replace its currency, the złoty, with the euro.

Stanisław Andrzej Michalkiewicz is a Polish far-right political commentator, lawyer, former politician, opposition activist in the communist Polish People's Republic, and book author.

The Poles in Lithuania, also called Lithuanian Poles, estimated at 183,000 people in the Lithuanian census of 2021 or 6.5% of Lithuania's total population, are the country's largest ethnic minority.

Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland after Auschwitz: An Essay in Historical Interpretation, is a book by Jan T. Gross, published by Random House and Princeton University Press in 2006. An edited Polish version was published in 2008 by Znak Publishers in Kraków as Strach: antysemityzm w Polsce tuż po wojnie: historia moralnej zapaści. In the book, Gross explores the issues concerning incidents of post-war anti-Jewish violence in Poland, with particular focus on the 1946 Kielce pogrom. Fear has received international attention and reviews in major newspapers; receiving both praise and criticism.

Jan Błoński was a Polish historian, literary critic, publicist and translator. He was a leading representative of the Kraków school of literary criticism, which wielded significant influence in postwar Poland.

Atheism and irreligiosity are uncommon theological beliefs in the country of Poland, with a majority of the country's population subscribing to Roman Catholicism. However, religious demographics have declined in recent decades, contributing to social tension within the country. According to a 2020 CBOS survey, non-believers now make up 3% of Poland's population.

Left Together is a social democratic political party in Poland.

Wojciech Jerzy Muszyński is a Polish historian. His areas of interest are the recent history of Poland and military history.

Jan Krzysztof Żaryn is a Polish historian, professor and politician, who was a Senator in the Senate of Poland from 2015 to 2019.

Klementyna Suchanow is a Polish author, editor, and activist. She is the co-founder of the women's rights movement All-Poland Women's Strike.

A Polish withdrawal from the European Union, or Polexit, is the name given to a hypothetical Polish withdrawal from the European Union. The term was coined after Brexit, the process of Britain's withdrawal from the EU which took place between 2016 and 2020. Opinion polls held in the country, between 2016 and 2021, indicated majority support for continued membership of the European Union (EU). A 2022 survey indicated that "[at] least eight-in-ten adults in Poland" believed that the EU "promotes peace, democratic values and prosperity". The 2023 Polish parliamentary election was won by a coalition of predominantly pro-EU parties.

The Roman Dmowski and Ignacy Jan Paderewski Institute for the Legacy of Polish National Thought is a Polish educational and historical research institute. Announced to appear at a press conference on 3 February 2020, it was formally inaugurated by the Minister of Culture and National Heritage, Piotr Gliński, on 17 February that year.

Falanga is a Polish national radical organization which was founded in January 2009. It is led by Bartosz Bekier, former coordinator of the Masovian Brigade of the National Radical Camp (ONR).

Marian Kałuski - Polish-Australian journalist, writer, historian and traveler.

The Independence March is an annual patriotic and nationalist demonstration in Warsaw held on Poland's Independence Day, November 11. Since 2011 the March has attracted annually up to 10 thousand participants. In 2020 the March was organized like a car procession. It is organized by far-right ultranationalist organisations and parties: National Radical Camp (ONR), All-Poland Youth and the National Movement.