Dada or Dadaism was an anti-establishment art movement that developed in 1915 in the context of the Great War and the earlier anti-art movement. Early centers for dadaism included Zürich and Berlin. Within a few years, the movement had spread to New York City and a variety of artistic centers in Europe and Asia.

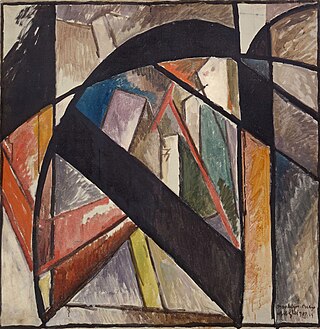

Cubism is an early-20th-century avant-garde art movement begun in Paris that revolutionized painting and the visual arts, and influenced artistic innovations in music, ballet, literature, and architecture. Cubist subjects are analyzed, broken up, and reassembled in an abstract form—instead of depicting objects from a single perspective, the artist depicts the subject from multiple perspectives to represent the subject in a greater context. Cubism has been considered the most influential art movement of the 20th century. The term cubism is broadly associated with a variety of artworks produced in Paris or near Paris (Puteaux) during the 1910s and throughout the 1920s.

Henri-Robert-Marcel Duchamp was a French painter, sculptor, chess player, and writer whose work is associated with Cubism, Dada, and conceptual art. He is commonly regarded, along with Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, as one of the three artists who helped to define the revolutionary developments in the plastic arts in the opening decades of the 20th century, responsible for significant developments in painting and sculpture. He has had an immense impact on 20th- and 21st-century art, and a seminal influence on the development of conceptual art. By the time of World War I, he had rejected the work of many of his fellow artists as "retinal", intended only to please the eye. Instead, he wanted to use art to serve the mind.

A found object, or found art, is art created from undisguised, but often modified, items or products that are not normally considered materials from which art is made, often because they already have a non-art function. Pablo Picasso first publicly utilized the idea when he pasted a printed image of chair caning onto his painting titled Still Life with Chair Caning (1912). Marcel Duchamp is thought to have perfected the concept several years later when he made a series of readymades, consisting of completely unaltered everyday objects selected by Duchamp and designated as art. The most famous example is Fountain (1917), a standard urinal purchased from a hardware store and displayed on a pedestal, resting on its back. In its strictest sense the term "readymade" is applied exclusively to works produced by Marcel Duchamp, who borrowed the term from the clothing industry while living in New York, and especially to works dating from 1913 to 1921.

Jacques Villon, also known as Gaston Duchamp, was a French Cubist and abstract painter and printmaker.

Raymond Duchamp-Villon was a French sculptor.

Jean Crotti was a French painter.

Suzanne Duchamp-Crotti was a French Dadaist painter, collagist, sculptor, and draughtsman. Her work was significant to the development of Paris Dada and modernism and her drawings and collages explore fascinating gender dynamics. Due to the fact that she was a woman in the male prominent Dada movement, she was rarely considered an artist in her own right. She constantly lived in the shadows of her famous older brothers, who were also artists, or she was referred to as "the wife of." Her work in painting turns out to be significantly influential to the landscape of Dada in Paris and to the interests of women in Dada. She took a large role as an avant-garde artist, working through a career that spanned five decades, during a turbulent time of great societal change. She used her work to express certain subject matter such as personal concerns about modern society, her role as a modern woman artist, and the effects of the First World War. Her work often weaves painting, collage, and language together in complex ways.

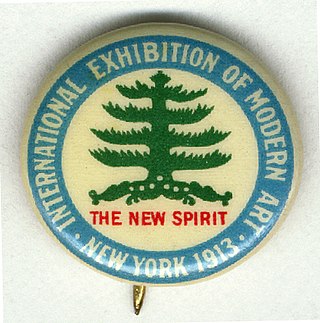

The 1913 Armory Show, also known as the International Exhibition of Modern Art, was organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors. It was the first large exhibition of modern art in America, as well as one of the many exhibitions that have been held in the vast spaces of U.S. National Guard armories.

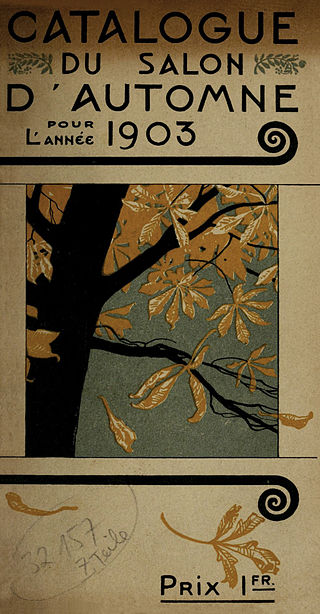

The Salon d'Automne, or Société du Salon d'automne, is an art exhibition held annually in Paris. Since 2011, it is held on the Champs-Élysées, between the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais, in mid-October. The first Salon d'Automne was created in 1903 by Frantz Jourdain, with Hector Guimard, George Desvallières, Eugène Carrière, Félix Vallotton, Édouard Vuillard, Eugène Chigot and Maison Jansen.

Society of Independent Artists was an association of American artists founded in 1916 and based in New York.

Fountain is a readymade sculpture by Marcel Duchamp in 1917, consisting of a porcelain urinal signed "R. Mutt". In April 1917, an ordinary piece of plumbing chosen by Duchamp was submitted for the inaugural exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, to be staged at the Grand Central Palace in New York. When explaining the purpose of his readymade sculpture, Duchamp stated they are "everyday objects raised to the dignity of a work of art by the artist's act of choice." In Duchamp's presentation, the urinal's orientation was altered from its usual positioning. Fountain was not rejected by the committee, since Society rules stated that all works would be accepted from artists who paid the fee, but the work was never placed in the show area. Following that removal, Fountain was photographed at Alfred Stieglitz's studio, and the photo published in the Dada journal The Blind Man. The original has been lost.

Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 is a 1912 painting by Marcel Duchamp. The work is widely regarded as a Modernist classic and has become one of the most famous of its time. Before its first presentation at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants in Paris it was rejected by the Cubists as being too Futurist. It was then exhibited with the Cubists at Galeries Dalmau's Exposició d'Art Cubista, in Barcelona, 20 April – 10 May 1912. The painting was subsequently shown, and ridiculed, at the 1913 Armory Show in New York City.

The readymades of Marcel Duchamp are ordinary manufactured objects that the artist selected and modified, as an antidote to what he called "retinal art". By simply choosing the object and repositioning or joining, titling and signing it, the found object became art.

New York Dada was a regionalized extension of Dada, an artistic and cultural movement between the years 1913 and 1923. Usually considered to have been instigated by Marcel Duchamp's Fountain exhibited at the first exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in 1917, and becoming a movement at the Cabaret Voltaire in February, 1916, in Zürich, the Dadaism as a loose network of artists spread across Europe and other countries, with New York becoming the primary center of Dada in the United States. The very word Dada is notoriously difficult to define and its origins are disputed, particularly amongst the Dadaists themselves.

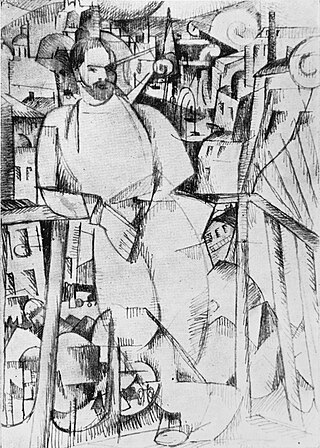

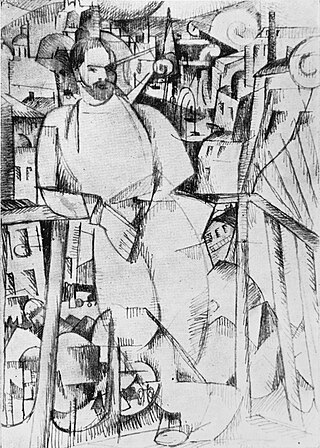

Man on a Balcony, is a large oil painting created in 1912 by the French artist, theorist and writer Albert Gleizes (1881–1953). The painting was exhibited in Paris at the Salon d'Automne of 1912. The Cubist contribution to the salon created a controversy in the French Parliament about the use of public funds to provide the venue for such 'barbaric art'. Gleizes was a founder of Cubism, and demonstrates the principles of the movement in this monumental painting with its projecting planes and fragmented lines. The large size of the painting reflects Gleizes's ambition to show it in the large annual salon exhibitions in Paris, where he was able with others of his entourage to bring Cubism to wider audiences.

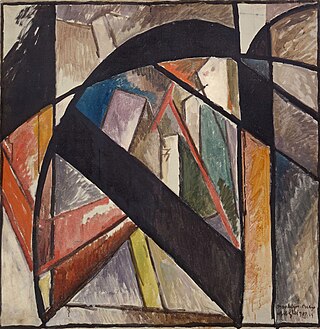

Brooklyn Bridge is a 1915 painting by the French artist, theorist and writer Albert Gleizes. Brooklyn Bridge was exhibited at the Montross Gallery, New York, 1916 along with works by Jean Crotti, Marcel Duchamp and Jean Metzinger.

Juliette Roche (1884–1980), also known as Juliette Roche Gleizes, was a French painter and writer who associated with members of the Cubist and Dada movements. She was married to the artist Albert Gleizes.

Louise Varèse, also credited as Louise Norton or Louise Norton-Varèse, was an American writer, editor, and translator of French literature who was involved with New York Dadaism.

Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette is a work of art by Marcel Duchamp, with the assistance of Man Ray. First conceived in 1920, created spring of 1921, Belle Haleine is one of the Readymades of Marcel Duchamp, or more specifically a rectified ready-made.