Yunus Emre also known as Derviş Yunus (1238–1328) was a Turkish folk poet and Islamic Sufi mystic who greatly influenced Turkish culture. His name, Yunus, is the Turkish equivalent to the English name Jonah. He wrote in Old Anatolian Turkish, an early stage of Turkish. The UNESCO General Conference unanimously passed a resolution declaring 1991, the 750th anniversary of the poet's birth, International Yunus Emre Year.

The Bektashi Order or Bektashism is an Islamic Sufi mystic order originating in the 13th-century. It is named after the Turkish saint Haji Bektash Veli. The Albanian community is currently led by Baba Mondi, their eighth Bektashi Dedebaba and headquartered in Tirana, Albania.

The culture of Turkey combines a heavily diverse and heterogeneous set of elements that have been derived from the various cultures of the Eastern European, Eastern Mediterranean, Caucasian, Middle East and Central Asian traditions. Many of these traditions were initially brought together by the Ottoman Empire, a multi-ethnic and multi-religious state spanning across Central Europe, Eastern Europe, the Middle East and North Africa.

Turkish literature comprises oral compositions and written texts in the Turkish language. The Ottoman form of Turkish, which forms the basis of much of the written corpus, was highly influenced by Persian and Arabic literature, and used the Ottoman Turkish alphabet.

Alevism or Anatolian Alevism is a local Islamic tradition, whose adherents follow the mystical Alevi Islamic teachings of Haji Bektash Veli, who is supposed to have taught the teachings of Ali and the Twelve Imams. Differing from Sunnism and other Twelver Shia, Alevis have no binding religious dogmas, and teachings are passed on by a spiritual leader. They acknowledge the six articles of faith of Islam, but may differ regarding their interpretation. Adherents of Alevism are found primarily in Turkey and estimates of the percentage of Turkey's population that are Alevi include between 4% and 15%.

Azerbaijani literature is written in Azerbaijani, a Turkic language, which is the official state language of the Republic of Azerbaijan, where the North Azerbaijani variety is spoken. It is also natively spoken in Iran, where the South Azerbaijani variety is used, and is particularly spoken in the northwestern historic region of Azerbaijan. Azerbaijani is also spoken natively in Russia, Georgia and Turkey. While the majority of Azerbaijani people live in Iran, modern Azerbaijani literature is overwhelmingly produced in the Republic of Azerbaijan, where the language has official status. Three scripts are used for writing the language: Azerbaijani Latin script in the Republic of Azerbaijan, Arabic script in Iran and Cyrillic script formerly used in Soviet Azerbaijan.

Haji Bektash Veli was a Muslim mystic, saint, sayyid, and philosopher from Khorasan who lived and taught in Anatolia. He is revered among Alevis for an Islamic understanding that is esoteric, rational and humanistic. Alevi and Bektashi Muslims believe the path of Haji Bektash is the path of Haqq-Muhammad-Ali since they were the source of Bektash's teachings. He was one of the many figures who flourished in the Sultanate of Rum and had an important influence on the culture of Turkish nomads of Asia Minor. His original name was Sayyid Muhammad ibn Sayyid Ibrāhim Ātā. He is also referred to as the "Sultan of Hearts" and the "Dervish of the Dervishes". Haji Bektash Veli was a descendant of Musa al-Kazim, the Seventh Imam of Twelver Shi'a Islam.

The Book of Dede Korkut or Book of Korkut Ata is the most famous among the epic stories of the Oghuz Turks. The stories carry morals and values significant to the social lifestyle of the nomadic Turkic peoples and their pre-Islamic beliefs. The book's mythic narrative is part of the cultural heritage of the peoples of Oghuz Turkic origin, mainly of Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Turkmenistan. Only two manuscripts of the text, one in the Vatican and one in Dresden, were known until 2018, when the Gonbad manuscript was discovered.

Folk religious practices remain in the Bektashiyyah tariqa and certain practices are also found to a lesser extent in Balkan Christianity and non-Bektashi Balkan Islam as well, according to some Western Islamic scholars.

An ashik or ashugh is traditionally a singer-poet and bard who accompanies his song—be it a dastan or a shorter original composition—with a long-necked lute in Turkic and non-Turkic cultures of South Caucasus. In Azerbaijan, the modern ashik is a professional musician who usually serves an apprenticeship, masters playing the bağlama, and builds up a varied but individual repertoire of Turkic folk songs.

The tradition of folklore—folktales, jokes, legends, and the like—in the Turkish language is very rich, and is incorporated into everyday life and events.

The Epic of Koroghlu is a heroic legend prominent in the oral traditions of the Turkic peoples, mainly the Oghuz Turks. The legend typically describes a hero who seeks to avenge a wrong. It was often put to music and played at sporting events as an inspiration to the competing athletes. Koroghlu is the main hero of epic with the same name in Azerbaijani, Turkmen and Turkish as well as some other Turkic languages. The epic tells about the life and heroic deeds of Koroghlu as a hero of the people who struggled against unjust rulers. The epic combines the occasional romance with Robin Hood-like chivalry.

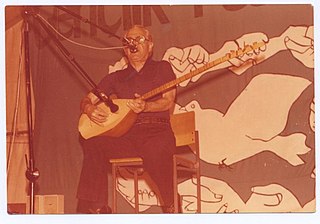

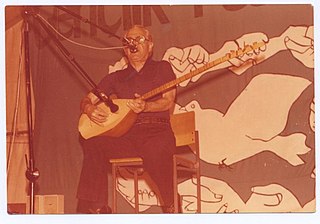

Mehmet Ruhi Su was a Turkish opera singer, Turkish folk singer and saz virtuoso of probable Armenian origin.

The History of the Shī‘ah Imāmī Alevī Ṭarīqah or The History of the Alevism is that of a community of Muslims

Sarı Saltık was a 13th-century Alevi Turkish dervish, venerated as a saint by the Bektashi Sufi Muslims in the Balkans and parts of Middle East as well as the mainstream Sunni Muslim community.

Otman Baba was a 15th-century dervish who traveled throughout the Ottoman Empire, acquiring a following among Muslims in Bulgaria after 1445 that has developed into his veneration as a saint. After Otman Baba's death, a pilgrimage complex grew around his grave in the present-day Bulgarian village of Teketo, which was made a museum during communism. The hagiography of Otman Baba, written by his disciple Küçük Abdal and regarded by his followers as a canonical text, maintains that Otman Baba performed miracles that proved his superiority to other dervishes and Ottoman authorities, particularly Sultan Mehmed II. Straying from orthodox Islamic tenets, Otman Baba asserted his unity with God and his mastery of divine secrets—as the embodiment of monotheistic religious figures such as Muhammad, Jesus, and Moses.

Azerbaijani folklore is the folk tradition of Azerbaijani people which has developed throughout the centuries. Azerbaijani folklore is embodied explicitly in a large collection of narratives and implicitly in representational arts, such as vase painting and votive gifts.

Reshat Bardhi or Dedebaba Hajji Reshat was an Albanian religious leader who served as the 7th kryegjysh or Dedebaba of the Bektashi Order from 1991 to 2011.

The Bektashi Order is an Islamic Sufi order that spread to Albania through Albanian Janissaries during the period of Ottoman control in Albania. The Bektashi make up 20% of Albania's Muslim population and 2.5% of the country's population. In Albania, the Bektashi Order has taken on a patriotic and nationalistic character, and it has played a major role in the Albanian National Awakening. Bektashi leaders have historically been prominent members in Albanian movements for self-determination and national autonomy, which has contributed to its popularity amongst the Albanians, and for most of Albania's Bektashi community, their affiliation with the order is based on cultural heritage rather than actual religious belief. In regards to ethics, the Bektashi adhere to the line - Be master of your hands, your tongue, and your loins - which essentially means do not steal, do not lie or speak idly, and do not commit adultery.