The Delhi Sultanate or the Sultanate of Delhi was a late medieval empire primarily based in Delhi that stretched over large parts of the Indian subcontinent, for more than three centuries. The sultanate was established around c. 1206–1211 in the former Ghurid territories in India. The sultanate's history is generally divided into five periods: Mamluk (1206–1290), Khalji (1290–1320), Tughlaq (1320–1414), Sayyid (1414–1451), and Lodi (1451–1526). It covered large swaths of territory in modern-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, as well as some parts of southern Nepal.

Ghilman were slave-soldiers and/or mercenaries in armies throughout the Islamic world. Islamic states from the early 9th century to the early 19th century consistently deployed slaves as soldiers, a phenomenon that was very rare outside of the Islamic world.

The Timurid Empire was a late medieval, culturally Persianate Turco-Mongol empire that dominated Greater Iran in the early 15th century, comprising modern-day Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, much of Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and parts of contemporary Pakistan, North India and Turkey. The empire was culturally hybrid, combining Turko-Mongolian and Persianate influences, with the last members of the dynasty being "regarded as ideal Perso-Islamic rulers".

The Sayyid dynasty was the fourth dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate, with four rulers ruling from 1414 to 1451 for 37 years. The first ruler of the dynasty, Khizr Khan, who was the Timurid vassal of Multan, conquered Delhi in 1414, while the rulers proclaimed themselves the Sultans of the Delhi Sultanate under Mubarak Shah, which succeeded the Tughlaq dynasty and ruled the Sultanate until they were displaced by the Lodi dynasty in 1451.

The Bahmani Kingdom or the Bahmani Sultanate was a late medieval kingdom that ruled the Deccan plateau in India. The first independent Muslim sultanate of the Deccan, the Bahmani Kingdom came to power in 1347 during the rebellion of Ismail Mukh against Muhammad bin Tughlaq, the Sultan of Delhi. Ismail Mukh then abdicated in favour of Zafar Khan, who established the Bahmani Sultanate.

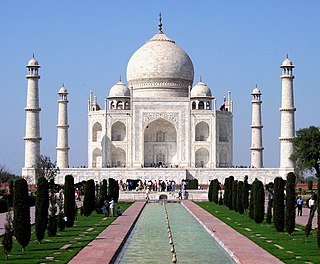

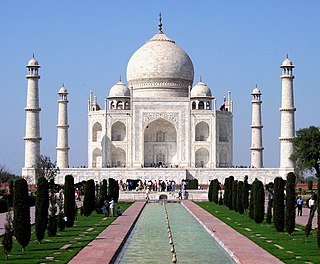

Indo-Persian culture refers to a cultural synthesis present on the Indian subcontinent. It is characterised by the absorption or integration of Persian aspects into the various cultures of modern-day republics of Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. The earliest introduction of Persian influence and culture to the subcontinent was by various Muslim Turko-Persian rulers, such as the 11th-century Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi, rapidly pushed for the heavy Persianization of conquered territories in northwestern Indian subcontinent, where Islamic influence was also firmly established. This socio-cultural synthesis arose steadily through the Delhi Sultanate from the 13th to 16th centuries, and the Mughal Empire from then onwards until the 19th century. Various dynasties of Turkic, Iranian and local Indian origin patronized the Persian language and contributed to the development of a Persian culture in India. The Delhi Sultanate developed their own cultural and political identity which built upon Persian and Indic languages, literature and arts, which formed the basis of an Indo-Muslim civilization.

The Mamluk dynasty, or the Mamluk Sultanate, is the historiographical name or umbrella term used to refer to the three dynasties of Mamluk origin who ruled the Ghurid territories in India and subsequently, the Sultanate of Delhi, from 1206 to 1290 — the Qutbi dynasty (1206–1211), the first Ilbari or Shamsi dynasty (1211–1266) and the second Ilbari dynasty (1266–1290).

The Khalji or Khilji dynasty was a Turco-Afghan dynasty that ruled the Delhi Sultanate for three decades between 1290 and 1320. It was the second dynasty to rule the Delhi Sultanate which covered large swaths of the Indian subcontinent. It was founded by Jalal ud din Firuz Khalji.

The Turco-Mongol or Turko-Mongol tradition was an ethnocultural synthesis that arose in Asia during the 14th century among the ruling elites of the Golden Horde and the Chagatai Khanate. The ruling Mongol elites of these khanates eventually assimilated into the Turkic populations that they conquered and ruled over, thus becoming known as Turco-Mongols. These elites gradually adopted Islam, as well as Turkic languages, while retaining Mongol political and legal institutions.

Jalal-ud-Din Khalji, also known as Firuz al-Din Khalji or Jalaluddin Khilji was the founder and first Sultan of the Khalji dynasty that ruled the Delhi Sultanate of India from 1290 to 1320.

Ghiyas-ud-din Balban was the ninth Sultan of Delhi. He had been the regent of the last Shamsi sultan, Mahmud until the latter's death in 1266, following which, he declared himself sultan of Delhi.

Malik Ambar was a military leader and statesman who served as the Peshwa of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate and its de facto ruler from 1600 until his death in 1626.

Rukn-ud-din Firuz, also transliterated as Rukn al-Din Firoz, was a ruler of Delhi sultanate for less than seven months in 1236. As a prince, he had administered the Badaun and Lahore provinces of the Sultanate. He ascended the throne after the death of his father Iltutmish, a powerful Mamluk ruler who had established the Sultanate as the most powerful kingdom in northern India. However, he pursued pleasure, wine, women, and left his mother Shah Turkan in control of the administration. The misadministration led to rebellions against Ruknuddin and his mother, both of whom were arrested and imprisoned. The nobles and the army subsequently appointed his half-sister Razia on the throne.

The composite Turko-Persian, Turco-Persian, or Turco-Iranian is the distinctive culture that arose in the 9th and 10th centuries AD in Khorasan and Transoxiana. According to the modern historian Robert L. Canfield, the Turco-Persian tradition was Persianate in that it was centered on a lettered tradition of Iranian origin; it was Turkic in so far as it was for many generations patronized by rulers of Turkic ancestry; and it was "Islamicate" in that Islamic notions of virtue, permance, and excellence infused discourse about public issues as well as the religious affairs of the Muslims, who were the presiding elite."

The Early History of slavery in the Indian subcontinent is contested because it depends on the translations of terms such as dasa and dasyu. Greek writer Megasthenes, in his 4th century BCE work Indika or Indica, states that slavery was banned within the Maurya Empire, while the multilingual, mid 3rd Century BCE, Edicts of Ashoka independently identify obligations to slaves and hired workers, within the same Empire.

The Mongol Empire launched numerous invasions into the Indian subcontinent from 1221 to 1327, with many of the later raids made by the Qara'unas of Mongol origin. The Mongols occupied parts of the subcontinent for decades. As the Mongols progressed into the Indian hinterland and reached the outskirts of Delhi, the Delhi Sultanate of India led a campaign against them in which the Mongol army suffered serious defeats.

Before British colonisation, the Persian language was the lingua franca of the Indian subcontinent and a widely used official language in North India. The language was brought into South Asia by various Turkics and Afghans and was preserved and patronized by Local Indian dynasties from the 11th century onwards, notable of which were the Ghaznavids, Sayyid Dynasty, Tughlaq dynasty, Khilji dynasty, Mughal Dynasty, Gujarat Sultanate, Bengal sultanate etc. Initially it was used by Muslim dynasties of India but later started being used by Non-Muslim empires too, For example the Sikh empire, Persian held official status in the court and the administration within these empires. It largely replaced Sanskrit as the language of politics, literature, education, and social status in the subcontinent.

Alp Khan was a general and brother-in-law of the Delhi Sultanate ruler Alauddin Khalji. He served as Alauddin's governor of Gujarat, and held considerable influence at the royal court of Delhi during the last years of Alauddin's life. He was executed on the charges of conspiring to kill Alauddin, possibly because of a conspiracy by Malik Kafur.

Ramya Sreenivasan is an Indian scholar of English and early modern Indian history. She is an associate professor in the Department of History at the University of Pennsylvania. She was originally appointed in the Department of South Asian Studies in 2009. Best known for her book The Many Lives of a Rajput Queen, she is a winner of the Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy Prize.

The Bukhara slave trade refers to the historical slave trade conducted in the city of Bukhara in Central Asia from antiquity until the 19th century. Bukhara and nearby Khiva were known as the major centers of slave trade in Central Asia for centuries until the completion of the Russian conquest of Central Asia in the late 19th century.