Related Research Articles

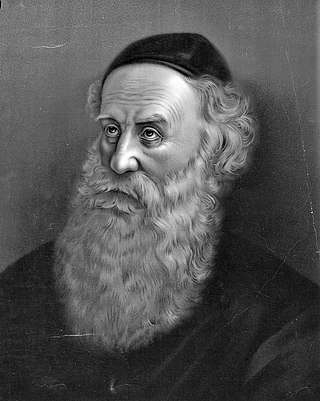

Shneur Zalman of Liadi was a rabbi and the founder and first Rebbe of Chabad, a branch of Hasidic Judaism. He wrote many works, and is best known for Shulchan Aruch HaRav, Tanya, and his Siddur Torah Or compiled according to the Nusach Ari.

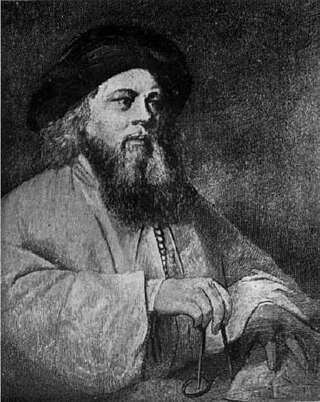

Dov Ber ben Avraham of Mezeritch, also known as the Maggid of Mezeritch or Mezeritcher Maggid, was a disciple of Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer, the founder of Hasidic Judaism, and was chosen as his successor to lead the early movement. Dov Ber is regarded as the first systematic exponent of the mystical philosophy underlying the teachings of the Baal Shem Tov, and through his teaching and leadership, the main architect of the movement. He established his base in Mezhirichi, which moved the centre of Hasidism from Medzhybizh, where he focused his attention on raising a close circle of disciples to spread the movement. After his death the third generation of leadership took their different interpretations and disseminated across appointed regions of Eastern Europe, rapidly spreading Hasidism beyond Ukraine, to Poland, Galicia and Russia.

Shema Yisrael is a Jewish prayer that serves as a centerpiece of the morning and evening Jewish prayer services. Its first verse encapsulates the monotheistic essence of Judaism: "Hear, O Israel: YHWH is our God, YHWH is one", found in Deuteronomy 6:4.

The Tanya is an early work of Hasidic philosophy, by Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder of Chabad Hasidism, first published in 1796. Its formal title is Likkutei Amarim, but is more commonly known by its first Hebrew word tanya, which means "it has been taught", where he refers to a baraita section in "Niddah", at the end of chapter 3, 30b. Tanya is composed of five sections that define Hasidic mystical psychology and theology as a handbook for daily spiritual life in Jewish observance.

Breslov is a branch of Hasidic Judaism founded by Rebbe Nachman of Breslov (1772–1810), a great-grandson of the Baal Shem Tov, founder of Hasidism. Its adherents strive to develop an intense, joyous relationship with God, and receive guidance toward this goal from the teachings of Rebbe Nachman.

Devekut, debekuth, deveikuth or deveikus is a Jewish concept referring to closeness to God. It may refer to a deep, trance-like meditative state attained during Jewish prayer, Torah study, or when performing the 613 commandments. It is particularly associated with the Jewish mystical tradition.

Hitbodedut or hisbodedus refers to practices of self-secluded Jewish meditation. The term was popularized by Rebbe Nachman of Breslov (1772–1810) to refer to an unstructured, spontaneous, and individualized form of prayer and meditation through which one would establish a close, personal relationship with God and ultimately see the Divinity inherent in all being.

Dovber Schneuri was the second Rebbe of the Chabad Lubavitch Chasidic movement. Rabbi Dovber was the first Chabad rebbe to live in the town of Lyubavichi, the town for which this Hasidic dynasty is named. He is also known as the Mitteler Rebbe, being the second of the first three generations of Chabad leaders.

Shuckling, from the Yiddish word meaning "to shake", is the ritual swaying of worshippers during Jewish prayer, usually forward and back but also from side to side.

Jewish meditation includes practices of settling the mind, introspection, visualization, emotional insight, contemplation of divine names, or concentration on philosophical, ethical or mystical ideas. Meditation may accompany unstructured, personal Jewish prayer, may be part of structured Jewish services, or may be separate from prayer practices. Jewish mystics have viewed meditation as leading to devekut. Hebrew terms for meditation include hitbodedut or hitbonenut/hisbonenus ("contemplation").

Hasidic philosophy or Hasidism, alternatively transliterated as Hasidut or Chassidus, consists of the teachings of the Hasidic movement, which are the teachings of the Hasidic rebbes, often in the form of commentary on the Torah and Kabbalah. Hasidism deals with a range of spiritual concepts such as God, the soul, and the Torah, dealing with esoteric matters but often making them understandable, applicable and finding practical expressions.

Practical Kabbalah in historical Judaism, is a branch of the Jewish mystical tradition that concerns the use of magic. It was considered permitted white magic by its practitioners, reserved for the elite, who could separate its spiritual source from Qliphoth realms of evil if performed under circumstances that were holy (Q-D-Š) and pure, tumah and taharah. The concern of overstepping Judaism's strong prohibitions of impure magic ensured it remained a minor tradition in Jewish history. Its teachings include the use of Divine and angelic names for amulets and incantations.

Divine providence is discussed throughout rabbinic literature, by the classical Jewish philosophers, and by the tradition of Jewish mysticism.

Chabad philosophy comprises the teachings of the leaders of Chabad-Lubavitch, a Hasidic movement. Chabad Hasidic philosophy focuses on religious concepts such as God, the soul, and the meaning of the Jewish commandments.

Keter Shem Tov was the first published work of the teachings of Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidism. The book was published in Zalkevo, 1794, more than thirty years after Rabbi Israel's passing. The book contains numerous, but brief, Hasidic interpretations of the Torah.

A Baal Shem was a historical Jewish practitioner of Practical Kabbalah and supposed miracle worker. Employing various methods, Baalei Shem are claimed to heal, enact miracles, perform exorcisms, treat various health issues, curb epidemics, protect people from disaster due to fire, robbery or the evil eye, foresee the future, decipher dreams, and bless those who sought his powers.

Israel ben Eliezer or Yisroel ben Eliezer, known as the Baal Shem Tov or as the BeShT, was a Jewish mystic and healer who is regarded as the founder of Hasidic Judaism. "Besht" is the acronym for Baal Shem Tov, which means "Master of the Good Name," a term for a holy man who wields the secret name of God.

Happiness in Judaism and Jewish thought is considered an important value, especially in the context of the service of God. A number of Jewish teachings stress the importance of joy, and demonstrate methods of attaining happiness.

Anger in Judaism is treated as a negative trait to be avoided whenever possible. The subject of anger is treated in a range of Jewish sources, from the Hebrew Bible and Talmud to the rabbinical law, Kabbalah, Hasidism, and contemporary Jewish sources.

References

- 1 2 Preface to Tzavaat HaRivash for the New Edition, by Rabbi Jacob Immanuel Schochet. (Hebrew)

- ↑ Tanya, Igeret HaKodesh, beg. ch. 25 (translated from Hebrew): Tzavaat HaRivash... which is actually not his "Testament" [at all]. And he did not instruct anything at all before his passing; rather, they are his pure, collected sayings, which were collected anthology after anthology.

- ↑ Teaching 5: One should attach one's thoughts Above, and not eat or drink more than is sufficient, and not indulge himself but for that which is healthy for himself. He should not look at things of the world, nor think of them at all; he should rather try in all things to separate himself from physicality... And it is written regarding the Tree of Knowledge "desirable to the sight and good for eating" - that because of seeing, it was desired.

- ↑ Teaching 9: And if thoughts of worldly lusts come to him, he should distance them from his thoughts and abandon the lust until he hates them and is disgusted by them. He should accustom his good inclination to over[power] the evil inclination and his lusts, and in this way subdue them.

- ↑ Tanya, Igeret HaKodesh, ch. 25