The Great Famine, also known as the Great Hunger, the Famine and the Irish Potato Famine, was a period of mass starvation and disease in Ireland lasting from 1845 to 1852 that constituted a historical social crisis and had a major impact on Irish society and history as a whole. The most severely affected areas were in the western and southern parts of Ireland—where the Irish language was dominant—hence the period was contemporaneously known in Irish as an Drochshaol, which literally translates to "the bad life" and loosely translates to "the hard times".

Timothy Patrick "Tim Pat" Coogan is an Irish journalist, writer and broadcaster. He served as editor of The Irish Press newspaper from 1968–87. He has been best known for such books as The IRA, Ireland Since the Rising and On the Blanket, and biographies of Michael Collins and Éamon de Valera.

John Mitchel was an Irish nationalist writer and journalist chiefly renowned for his indictment of British policy in Ireland during the years of the Great Famine. Concluding that, in Ireland, legal and constitutional agitation was a "delusion", Mitchel broke first with Daniel O'Connell's Repeal Association and then with his Young Ireland colleagues at the paper The Nation. In 1848, as editor of his own journal, United Irishman, he was convicted of seditious libel and sentenced to 14-years penal transportation for advocating James Fintan Lalor's programme of co-ordinated resistance to landlords and to the continued shipment of harvests to England.

James Craig, 1st Viscount CraigavonPC PC (NI) DL, was a leading Irish unionist and a key architect of Northern Ireland as a devolved region within the United Kingdom. During the Home Rule Crisis of 1912–14, he defied the British government in preparing an armed resistance in Ulster to an all-Ireland parliament. He accepted partition as a final settlement, securing the opt out of six Ulster counties from the dominion statehood accorded Ireland under the terms of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty. From then until his death in 1940, he led the Ulster Unionist Party and served Northern Ireland as its first Prime Minister. He publicly characterised his administration as a "Protestant" counterpart to the "Catholic state" nationalists had established in the south. Craig was created a baronet in 1918 and raised to the Peerage in 1927.

The legacy of the Great Famine in Ireland followed a catastrophic period of Irish history between 1845 and 1852 during which time the population of Ireland was reduced by 50 percent.

Andrew Bonar Law was a British statesman and Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

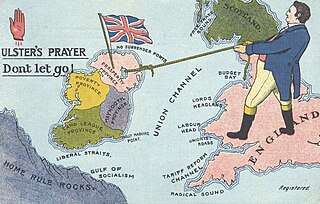

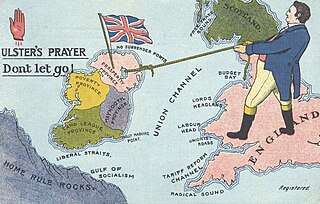

Unionism in Ireland is a political tradition that professes loyalty to the crown of the United Kingdom and to the union it represents with England, Scotland and Wales. The overwhelming sentiment of Ireland's Protestant minority, unionism mobilised in the decades following Catholic Emancipation in 1829 to oppose restoration of a separate Irish parliament. Since Partition in 1921, as Ulster unionism its goal has been to retain Northern Ireland as a devolved region within the United Kingdom and to resist the prospect of an all-Ireland republic. Within the framework of the 1998 Belfast Agreement, which concluded three decades of political violence, unionists have shared office with Irish nationalists in a reformed Northern Ireland Assembly. As of February 2024, they no longer do so as the larger faction: they serve in an executive with an Irish republican First Minister.

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cultural nationalism based on the principles of national self-determination and popular sovereignty. Irish nationalists during the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries such as the United Irishmen in the 1790s, Young Irelanders in the 1840s, the Fenian Brotherhood during the 1880s, Fianna Fáil in the 1920s, and Sinn Féin styled themselves in various ways after French left-wing radicalism and republicanism. Irish nationalism celebrates the culture of Ireland, especially the Irish language, literature, music, and sports. It grew more potent during the period in which all of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom, which led to most of the island gaining independence from the UK in 1922.

Walter Hume Long, 1st Viscount Long,, was a British Unionist politician. In a political career spanning over 40 years, he held office as President of the Board of Agriculture, President of the Local Government Board, Chief Secretary for Ireland, Secretary of State for the Colonies and First Lord of the Admiralty. He is also remembered for his links with Irish Unionism, and served as Leader of the Irish Unionist Party in the House of Commons from 1906 to 1910.

Ireland was part of the United Kingdom from 1801 to 1922. For almost all of this period, the island was governed by the UK Parliament in London through its Dublin Castle administration in Ireland. Ireland underwent considerable difficulties in the 19th century, especially the Great Famine of the 1840s which started a population decline that continued for almost a century. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a vigorous campaign for Irish Home Rule. While legislation enabling Irish Home Rule was eventually passed, militant and armed opposition from Irish unionists, particularly in Ulster, opposed it. Proclamation was shelved for the duration following the outbreak of World War I. By 1918, however, moderate Irish nationalism had been eclipsed by militant republican separatism. In 1919, war broke out between republican separatists and British Government forces. Subsequent negotiations between Sinn Féin, the major Irish party, and the UK government led to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which resulted in five-sixths of the island seceding from the United Kingdom, becoming the Irish Free State, with only the six northeastern counties remaining within the United Kingdom.

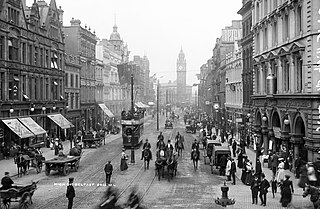

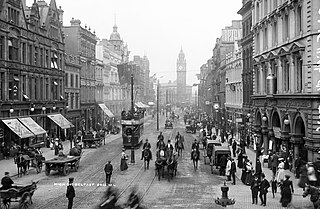

Belfast is the capital of Northern Ireland, and throughout its modern history has been a major commercial and industrial centre. In the late 20th century manufacturing industries that had existed for several centuries declined, particularly shipbuilding. The city's history has occasionally seen conflict between different political factions who favour different political arrangements between Ireland and Great Britain. Since the Good Friday Agreement, the city has been relatively peaceful and major redevelopment has occurred, especially in the inner city and dock areas.

John Joseph Clancy, usually known as J. J. Clancy, was an Irish nationalist politician and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons for North Dublin from 1885 to 1918. He was one of the leaders of the later Irish Home Rule movement and promoter of the Housing of the Working Classes (Ireland) Act 1908, known as the Clancy Act. Called to the Irish Bar in 1887, he became a King's Counsel in 1906.

Theodore William Moody was a historian from Belfast, Ireland.

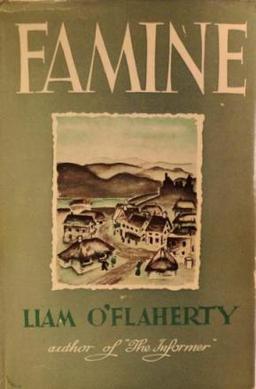

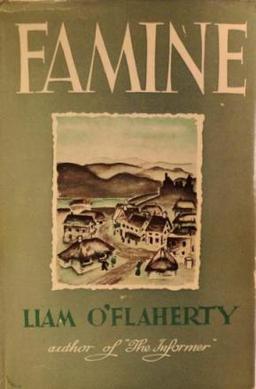

Famine is a novel by Irish writer Liam O'Flaherty published in 1937. Set in the fictionally named Black Valley in the west of Ireland during the Great Famine of the 1840s, the novel tells the story of three generations of the Kilmartin family. The novel is critical of the constitutional politics of Daniel O'Connell, which are depicted as laying the oppressed Irish of the 19th century open to the famine that would destroy their society.

The first evidence of human presence in Ireland dates to around 34,000 years ago, with further findings dating the presence of homo sapiens to around 10,500 to 7,000 BCE. The receding of the ice after the Younger Dryas cold phase of the Quaternary, around 9700 BCE, heralds the beginning of Prehistoric Ireland, which includes the archaeological periods known as the Mesolithic, the Neolithic from about 4000 BCE, and the Copper Age beginning around 2500 BCE with the arrival of the Beaker Culture. The Irish Bronze Age proper begins around 2000 BCE and ends with the arrival of the Iron Age of the Celtic Hallstatt culture, beginning about 600 BCE. The subsequent La Tène culture brought new styles and practices by 300 BCE.

The Irish slaves myth is a fringe pseudohistorical narrative that conflates the penal transportation and indentured servitude of Irish people during the 17th and 18th centuries, with the hereditary chattel slavery experienced by the forebears of the African diaspora.

Liam Kennedy is an Irish historian, emeritus professor of history at Queen's University, Belfast.

Revisionism in Irish historiography refers to a historical revisionist tendency and group of historians who are critical of the orthodox view of Irish history since the achievement of partial Irish independence, which comes from the perspective of Irish nationalism. For opponents, Revisionists are regarded as apologists for the British Empire in Ireland, proponents of a form of denialism and even in some cases advocates of neo-unionism, while the Revisionists on the other hand see themselves as positing a progressive cosmopolitan narrative opposed to a "narrowly sectarian" viewpoint.