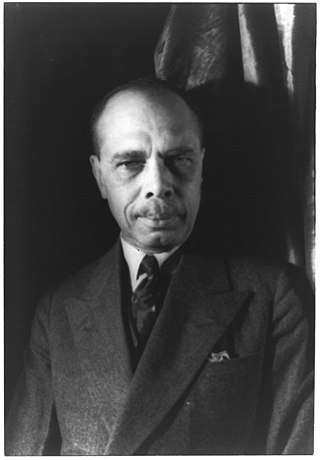

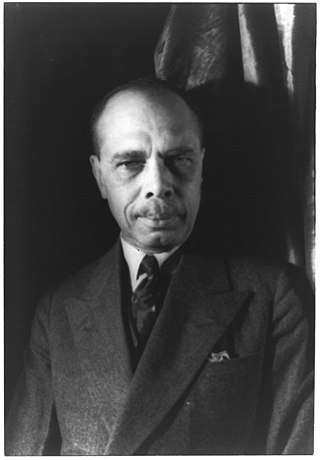

James Weldon Johnson was an American writer and civil rights activist. He was married to civil rights activist Grace Nail Johnson. Johnson was a leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), where he started working in 1917. In 1920, he was chosen as executive secretary of the organization, effectively the operating officer. He served in that position from 1920 to 1930. Johnson established his reputation as a writer, and was known during the Harlem Renaissance for his poems, novel and anthologies collecting both poems and spirituals of Black culture. He wrote the lyrics for "Lift Every Voice and Sing", which later became known as the Black National Anthem, the music being written by his younger brother, composer J. Rosamond Johnson.

The Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) is a black nationalist fraternal organization founded by Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican immigrant to the United States, and his then-wife Amy Ashwood Garvey. The African Nationalist organization enjoyed its greatest strength in the 1920s, and was influential prior to Garvey's deportation to Jamaica in 1927. After that its prestige and influence declined, but it had a strong influence on African-American history and development. The UNIA was said to be "unquestionably, the most influential anticolonial organization in Jamaica prior to 1938," according to Honor Ford-Smith.

An African American is a citizen or resident of the United States who has origins in any of the black populations of Africa. African American-related topics include:

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, was a historian, writer, curator, and activist. He also wrote many books. Schomburg was a Puerto Rican of African and German descent. He moved to the United States in 1891, settling in New York City where he researched and raised awareness of the contributions that Afro-Latin Americans and African Americans have made to society. He was an important intellectual figure in the Harlem Renaissance. Over the years, he collected literature, art, slave narratives, and other materials of African history, which were purchased to become the basis of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, named in his honor, at the New York Public Library (NYPL) branch in Harlem.

Aaron Douglas was an American painter, illustrator, and visual arts educator. He was a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance. He developed his art career painting murals and creating illustrations that addressed social issues around race and segregation in the United States by utilizing African-centric imagery. Douglas set the stage for young, African-American artists to enter the public-arts realm through his involvement with the Harlem Artists Guild. In 1944, he concluded his art career by founding the Art Department at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. He taught visual art classes at Fisk University until his retirement in 1966. Douglas is known as a prominent leader in modern African-American art whose work influenced artists for years to come.

Sundown towns, also known as sunset towns, gray towns, or sundowner towns, were all-white municipalities or neighborhoods in the United States. They were towns that practice a form of racial segregation by excluding non-whites via some combination of discriminatory local laws, intimidation or violence. They were most prevalent before the 1950s. The term came into use because of signs that directed "colored people" to leave town by sundown.

George Samuel Schuyler was an American writer, journalist, and social commentator known for his outspoken political conservatism after repudiating his earlier advocacy of socialism.

Joel Augustus Rogers was a Jamaican-American author, journalist, and amateur historian who focused on the history of Africa; as well as the African diaspora. After settling in the United States in 1906, he lived in Chicago and then New York City. He became interested in the history of African Americans in the United States. His research spanned the academic fields of history, sociology and anthropology. He challenged prevailing ideas about scientific racism and the social construction of race, demonstrated the connections between civilizations, and traced achievements of ethnic Africans, including some with mixed European ancestry. He was one of the earliest popularizers of African and African-American history in the 20th century. His book World's Great Men of Color was recognized by John Henrik Clarke as being his greatest achievement.

James W. “Jim” Ford was an activist, a politician, and the vice-presidential candidate for the Communist Party USA in the years 1932, 1936, and 1940. Ford was born in Alabama and later worked as a party organizer for the CPUSA in New York City. He was also the first African American to run on a U.S. presidential ticket (1932) in the 20th century.

Alain LeRoy Locke was an American writer, philosopher, and educator. Distinguished in 1907 as the first African American Rhodes Scholar, Locke became known as the philosophical architect—the acknowledged "Dean"—of the Harlem Renaissance. He is frequently included in listings of influential African Americans. On March 19, 1968, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. proclaimed: "We're going to let our children know that the only philosophers that lived were not Plato and Aristotle, but W. E. B. Du Bois and Alain Locke came through the universe."

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African-American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the time, it was known as the "New Negro Movement", named after The New Negro, a 1925 anthology edited by Alain Locke. The movement also included the new African-American cultural expressions across the urban areas in the Northeast and Midwest United States affected by a renewed militancy in the general struggle for civil rights, combined with the Great Migration of African-American workers fleeing the racist conditions of the Jim Crow Deep South, as Harlem was the final destination of the largest number of those who migrated north.

Hackensack Cemetery is a cemetery located in Hackensack, New Jersey, United States, founded by Baptists, Dutch Reformed, and Congregational benefactors in the 1890s, as a result of overcrowding in local churchyards and availability of open space. The same group of prominent Hackensack men organized the Johnson Free Public Library. It's the burial place of Edward D. Easton, & Ben E. King.

James Mercer Langston Hughes was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri. One of the earliest innovators of the literary form called jazz poetry, Hughes is best known as a leader of the Harlem Renaissance.

Rainbow Inn was an Afro-American hotel and restaurant in Petoskey, Michigan, that was in business from 1950 until 1965.

The Negro Motorist Green Book was a guidebook for African American roadtrippers. It was founded by Victor Hugo Green, an African American postal worker from New York City, and was published annually from 1936 to 1966. This was during the era of Jim Crow laws, when open and often legally prescribed discrimination against African Americans especially and other non-whites was widespread. While pervasive racial discrimination and poverty limited black car ownership, the emerging African American middle class bought automobiles as soon as they could but faced a variety of dangers and inconveniences along the road, from refusal of food and lodging to arbitrary arrest. In the South, where Black motorists risked harassment or physical violence, these dangers were particularly severe. In some cases, African American travelers who got lost or sought lodging off the beaten path were killed, with little to no investigation by local authorities. In response, Green wrote his guide to services and places relatively friendly to African Americans. Eventually, he also founded a travel agency.

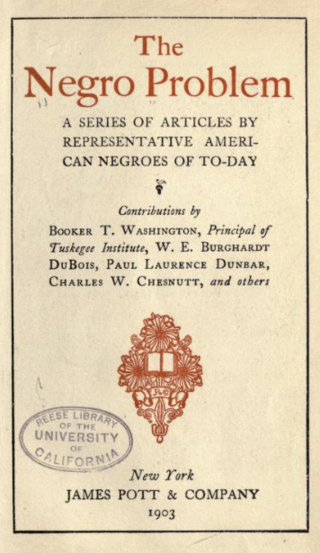

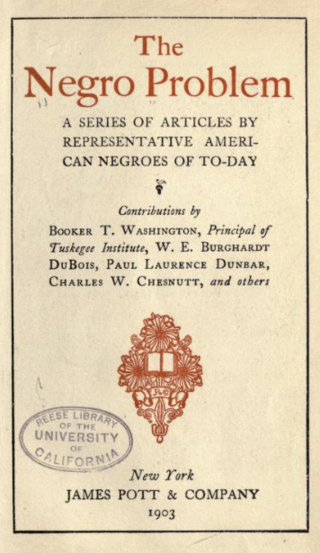

The Negro Problem is a collection of seven essays by prominent Black American writers, such as W. E. B. Du Bois and Paul Laurence Dunbar, edited by Booker T. Washington, and published in 1903. It covers law, education, disenfranchisement, and Black Americans' place in American society.

Derrick Adams is an American visual and performance artist and curator. Much of Adams' work is centered around his Black identity, frequently referencing patterns, images, and themes of Black culture in America. Adams has additionally worked as a fine art professor, serving as a faculty member at Maryland Institute College of Art.

Alma Vessells John was an American nurse, newsletter writer, radio and television personality, and civil rights activist. Born in Philadelphia in 1906, she moved to New York to take nursing classes after graduating from high school. She completed her nursing training at Harlem Hospital School of Nursing in 1929 and worked for two years as a nurse before being promoted to the director of the educational and recreational programs at Harlem Hospital. After being fired for trying to unionize nurses in 1938, she became the director of the Upper Manhattan YWCA School for Practical Nurses, the first African American to serve as director of a school of nursing in the state of New York.. In 1944, John became a lecturer and consultant with the National Nursing Council for War Service, serving until the war ended, and was the last director of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses from 1946 until it dissolved in 1951. Her position at both organizations was to expand nursing opportunities for black women and integrate black nurses throughout the nation into the health care system.

The Black Travel Movement is a socioentrepreneurial phenomenon that pursues social change by developing travel-related businesses that encourage Black people to travel. The movement emerged in the 2010s, but in the United States its historical roots go back to The Negro Motorist Green Book and to historically Black resorts.