A DNA vaccine is a type of vaccine that transfects a specific antigen-coding DNA sequence into the cells of an organism as a mechanism to induce an immune response.

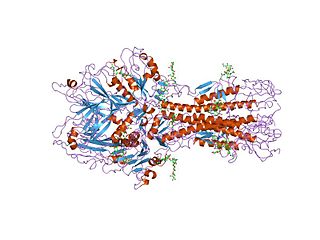

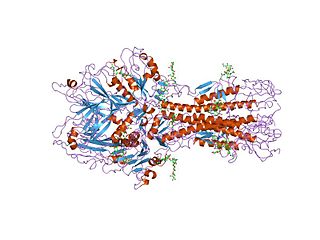

Influenza hemagglutinin (HA) or haemagglutinin[p] is a homotrimeric glycoprotein found on the surface of influenza viruses and is integral to its infectivity.

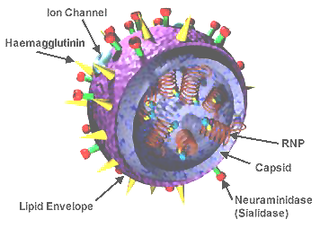

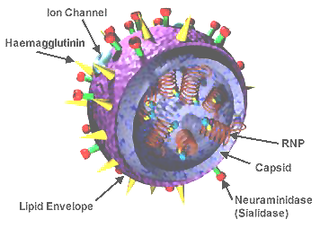

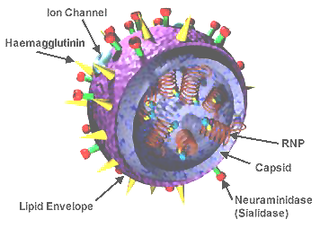

Orthomyxoviridae is a family of negative-sense RNA viruses. It includes seven genera: Alphainfluenzavirus, Betainfluenzavirus, Gammainfluenzavirus, Deltainfluenzavirus, Isavirus, Thogotovirus, and Quaranjavirus. The first four genera contain viruses that cause influenza in birds and mammals, including humans. Isaviruses infect salmon; the thogotoviruses are arboviruses, infecting vertebrates and invertebrates. The Quaranjaviruses are also arboviruses, infecting vertebrates (birds) and invertebrates (arthropods).

Antigenic drift is a kind of genetic variation in viruses, arising from the accumulation of mutations in the virus genes that code for virus-surface proteins that host antibodies recognize. This results in a new strain of virus particles that is not effectively inhibited by the antibodies that prevented infection by previous strains. This makes it easier for the changed virus to spread throughout a partially immune population. Antigenic drift occurs in both influenza A and influenza B viruses.

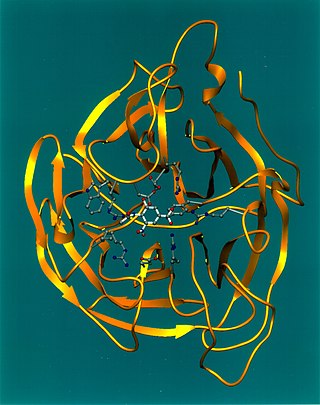

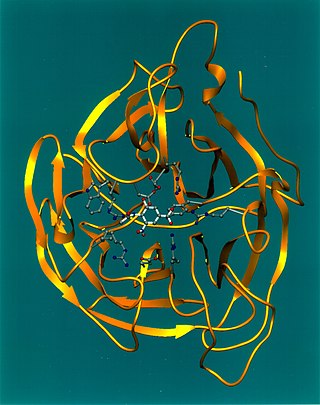

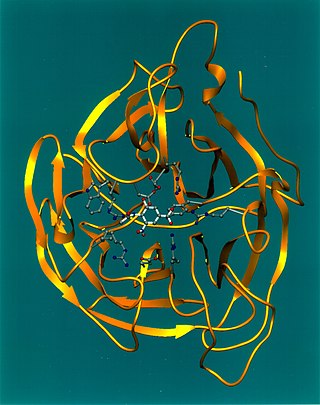

Exo-α-sialidase is a glycoside hydrolase that cleaves the glycosidic linkages of neuraminic acids:

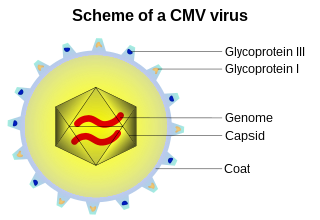

Virus-like particles (VLPs) are molecules that closely resemble viruses, but are non-infectious because they contain no viral genetic material. They can be naturally occurring or synthesized through the individual expression of viral structural proteins, which can then self assemble into the virus-like structure. Combinations of structural capsid proteins from different viruses can be used to create recombinant VLPs. Both in-vivo assembly and in-vitro assembly have been successfully shown to form virus-like particles. VLPs derived from the Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and composed of the small HBV derived surface antigen (HBsAg) were described in 1968 from patient sera. VLPs have been produced from components of a wide variety of virus families including Parvoviridae, Retroviridae, Flaviviridae, Paramyxoviridae and bacteriophages. VLPs can be produced in multiple cell culture systems including bacteria, mammalian cell lines, insect cell lines, yeast and plant cells.

Hemagglutinin esterase (HEs) is a glycoprotein that certain enveloped viruses possess and use as an invading mechanism. HEs helps in the attachment and destruction of certain sialic acid receptors that are found on the host cell surface. Viruses that possess HEs include influenza C virus, toroviruses, and coronaviruses of the subgenus Embecovirus. HEs is a dimer transmembrane protein consisting of two monomers, each monomer is made of three domains. The three domains are: membrane fusion, esterase, and receptor binding domains.

Influenza C virus is the only species in the genus Gammainfluenzavirus, in the virus family Orthomyxoviridae, which like other influenza viruses, causes influenza.

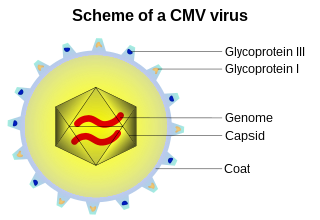

A viral envelope is the outermost layer of many types of viruses. It protects the genetic material in their life cycle when traveling between host cells. Not all viruses have envelopes. A viral envelope protein or E protein is a protein in the envelope, which may be acquired by the capsid from an infected host cell.

H5N1 genetic structure is the molecular structure of the H5N1 virus's RNA.

Antigenic variation or antigenic alteration refers to the mechanism by which an infectious agent such as a protozoan, bacterium or virus alters the proteins or carbohydrates on its surface and thus avoids a host immune response, making it one of the mechanisms of antigenic escape. It is related to phase variation. Antigenic variation not only enables the pathogen to avoid the immune response in its current host, but also allows re-infection of previously infected hosts. Immunity to re-infection is based on recognition of the antigens carried by the pathogen, which are "remembered" by the acquired immune response. If the pathogen's dominant antigen can be altered, the pathogen can then evade the host's acquired immune system. Antigenic variation can occur by altering a variety of surface molecules including proteins and carbohydrates. Antigenic variation can result from gene conversion, site-specific DNA inversions, hypermutation, or recombination of sequence cassettes. The result is that even a clonal population of pathogens expresses a heterogeneous phenotype. Many of the proteins known to show antigenic or phase variation are related to virulence.

Murine respirovirus, formerly Sendai virus (SeV) and previously also known as murine parainfluenza virus type 1 or hemagglutinating virus of Japan (HVJ), is an enveloped, 150-200 nm–diameter, negative sense, single-stranded RNA virus of the family Paramyxoviridae. It typically infects rodents and it is not pathogenic for humans or domestic animals

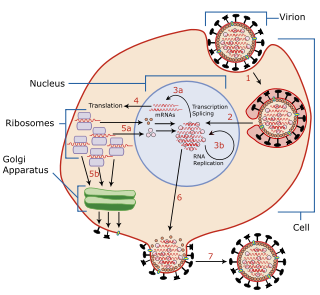

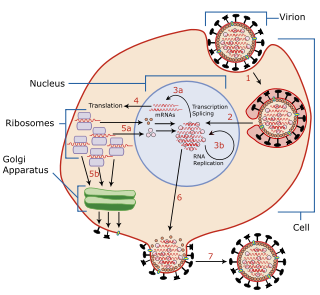

Viral entry is the earliest stage of infection in the viral life cycle, as the virus comes into contact with the host cell and introduces viral material into the cell. The major steps involved in viral entry are shown below. Despite the variation among viruses, there are several shared generalities concerning viral entry.

In virology, a spike protein or peplomer protein is a protein that forms a large structure known as a spike or peplomer projecting from the surface of an enveloped virus. The proteins are usually glycoproteins that form dimers or trimers.

Viral neuraminidase is a type of neuraminidase found on the surface of influenza viruses that enables the virus to be released from the host cell. Neuraminidases are enzymes that cleave sialic acid groups from glycoproteins. Neuraminidase inhibitors are antiviral agents that inhibit influenza viral neuraminidase activity and are of major importance in the control of influenza.

In molecular biology, hemagglutinins are receptor-binding membrane fusion glycoproteins produced by viruses in the Paramyxoviridae family. Hemagglutinins are responsible for binding to receptors on red blood cells to initiate viral attachment and infection. The agglutination of red cells occurs when antibodies on one cell bind to those on others, causing amorphous aggregates of clumped cells.

Hussein Naim is a Lebanese-Swiss biochemist and molecular virologist, known for his research in cell biology and virology. He has held several leading positions at prominent universities and biotechnology centers.

George Keble Hirst, M.D. was an American virologist and science administrator who was among the first to study the molecular biology and genetics of animal viruses, especially influenza virus. He directed the Public Health Research Institute in New York City (1956–1981), and was also the founding editor-in-chief of Virology, the first English-language journal to focus on viruses. He is particularly known for inventing the hemagglutination assay, a simple method for quantifying viruses, and adapting it into the hemagglutination inhibition assay, which measures virus-specific antibodies in serum. He was the first to discover that viruses can contain enzymes, and the first to propose that virus genomes can consist of discontinuous segments. The New York Times described him as "a pioneer in molecular virology."

A universal flu vaccine is a flu vaccine that is effective against all influenza strains regardless of the virus sub type, antigenic drift or antigenic shift. Hence it should not require modification from year to year. As of 2021 no universal flu vaccine had been approved for general use, several were in development, and one was in clinical trial.

Influenza D virus is a species in the virus genus Deltainfluenzavirus, in the family Orthomyxoviridae, that causes influenza.