A funeral is a ceremony connected with the final disposition of a corpse, such as a burial or cremation, with the attendant observances. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect the dead, from interment, to various monuments, prayers, and rituals undertaken in their honour. Customs vary between cultures and religious groups. Funerals have both normative and legal components. Common secular motivations for funerals include mourning the deceased, celebrating their life, and offering support and sympathy to the bereaved; additionally, funerals may have religious aspects that are intended to help the soul of the deceased reach the afterlife, resurrection or reincarnation.

Sukkot, also known as the Feast of Tabernacles or Feast of Booths, is a Torah-commanded holiday celebrated for seven days, beginning on the 15th day of the month of Tishrei. It is one of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals on which Israelites were commanded to make a pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem. Biblically an autumn harvest festival and a commemoration of the Exodus from Egypt, Sukkot’s modern observance is characterized by festive meals in a sukkah, a temporary wood-covered hut.

Shiva is the week-long mourning period in Judaism for first-degree relatives. The ritual is referred to as "sitting shiva" in English. The shiva period lasts for seven days following the burial. Following the initial period of despair and lamentation immediately after the death, shiva embraces a time when individuals discuss their loss and accept the comfort of others.

A bar mitzvah (masc.), or bat mitzvah (fem.) is a coming of age ritual in Judaism. According to Jewish law, before children reach a certain age, the parents are responsible for their child's actions. Once Jewish children reach that age, they are said to "become" b'nai mitzvah, at which point they begin to be held accountable for their own actions. Traditionally, the father of a bar or bat mitzvah offers thanks to God that he is no longer punished for his child's sins.

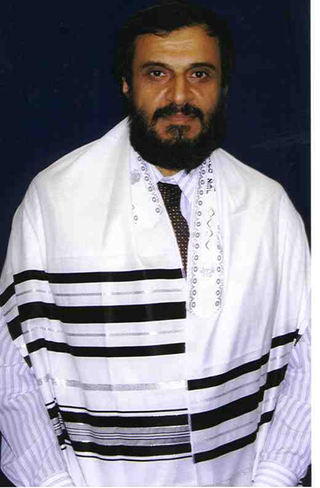

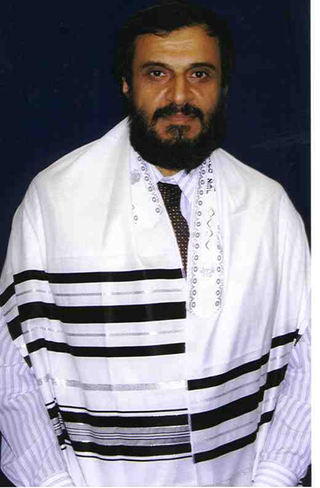

A tallit is a fringed garment worn as a prayer shawl by religious Jews. The tallit has special twined and knotted fringes known as tzitzit attached to its four corners. The cloth part is known as the beged ("garment") and is usually made from wool or cotton, although silk is sometimes used for a tallit gadol.

Chabad, also known as Lubavitch, Habad and Chabad-Lubavitch, is a dynasty in Hasidic Judaism. Belonging to the Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) branch of Orthodox Judaism, it is one of the world's best-known Hasidic movements, as well as one of the largest Jewish religious organizations. Unlike most Haredi groups, which are self-segregating, Chabad mainly operates in the wider world and caters to nonobservant Jews.

A gravestone or tombstone is a marker, usually stone, that is placed over a grave. A marker set at the head of the grave may be called a headstone. An especially old or elaborate stone slab may be called a funeral stele, stela, or slab. The use of such markers is traditional for Chinese, Jewish, Christian, and Islamic burials, as well as other traditions. In East Asia, the tomb's spirit tablet is the focus for ancestral veneration and may be removable for greater protection between rituals. Ancient grave markers typically incorporated funerary art, especially details in stone relief. With greater literacy, more markers began to include inscriptions of the deceased's name, date of birth, and date of death, often along with a personal message or prayer. The presence of a frame for photographs of the deceased is also increasingly common.

Yahrzeit is the anniversary of a death in Judaism. It is traditionally commemorated by reciting the Kaddish in synagogue and by lighting a long-burning candle.

The term chevra kadisha gained its modern sense of "burial society" in the nineteenth century. It is an organization of Jewish men and women who see to it that the bodies of deceased Jews are prepared for burial according to Jewish tradition and are protected from desecration, willful or not, until burial. Two of the main requirements are the showing of proper respect for a corpse, and the ritual cleansing of the body and subsequent dressing for burial. It is usually referred to as a burial society in English.

A siyum ("completion"), in Judaism, occasionally spelled siyyum, is the completion of any established unit of Torah study. The most common units are a single volume of the Talmud, or of Mishnah, but there are other units of learning that may lead to a siyum.

Bereavement in Judaism is a combination of minhag (traditions) and mitzvah (commandments) derived from the Torah and Judaism's classical rabbinic literature. The details of observance and practice vary according to each Jewish community.

The Priestly Blessing or priestly benediction, also known in rabbinic literature as raising of the hands, rising to the platform, dukhenen, or duchening, is a Hebrew prayer recited by Kohanim. The text of the blessing is found in Numbers 6:23–27. It is also known as the Aaronic blessing.

A Jewish cemetery is a cemetery where Jews are buried in keeping with Jewish tradition. Cemeteries are referred to in several different ways in Hebrew, including beit kevarot, beit almin, beit olam [haba], beit chayyim and beit shalom.

Orthodox Jewish outreach, often referred to as Kiruv or Qiruv, is the collective work or movement of Orthodox Judaism that reaches out to non-observant Jews to encourage belief in God and life according to Jewish law. The process of a Jew becoming more observant of Orthodox Judaism is called teshuva making the "returnee" a baal teshuva. Orthodox Jewish outreach has worked to enhance the rise of the baal teshuva movement.

Shemira refers to the Jewish religious ritual of watching over the body of a deceased person from the time of death until burial. A male guardian is called a shomer, and a female guardian is a shomeret. Shomrim are people who perform shemira. In Israel, shemira refers to all forms of guard duty, including military guard duty. An armed man or woman appointed to patrol a grounds or campus for security purposes would be called a shomer or shomeret.

A yahrzeit candle, also spelled yahrtzeit candle or called a memorial candle, is a type of candle that is lit in memory of the dead in Judaism.

An adult bar/bat mitzvah is a bar or bat mitzvah of a person older than the customary age. Traditionally, a bar or bat mitzvah occurs at age 13 for boys and 12 for girls. Many adult Jews who have never had a bar or bat mitzvah, however, may choose to have one later in life, and many who have had one at the traditional age choose to have a second. An adult bar or bat mitzvah can be held at any age after adulthood is reached and can be performed in a variety of ways.

Chabad customs and holidays are the practices, rituals and holidays performed and celebrated by adherents of the Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic movement. The customs, or minhagim and prayer services are based on Lurianic kabbalah. The holidays are celebrations of events in Chabad history. General Chabad customs, called minhagim, distinguish the movement from other Hasidic groups.

Coins for the dead is a form of respect for the dead or bereavement. The practice began in classical antiquity when people believed the dead needed coins to pay a ferryman to cross the river Styx. In modern times the practice has been observed in the United States and Canada: visitors leave coins on the gravestones of former military personnel.