Related Research Articles

Lean manufacturing is a method of manufacturing goods aimed primarily at reducing times within the production system as well as response times from suppliers and customers. It is closely related to another concept called just-in-time manufacturing. Just-in-time manufacturing tries to match production to demand by only supplying goods that have been ordered and focus on efficiency, productivity, and reduction of "wastes" for the producer and supplier of goods. Lean manufacturing adopts the just-in-time approach and additionally focuses on reducing cycle, flow, and throughput times by further eliminating activities that do not add any value for the customer. Lean manufacturing also involves people who work outside of the manufacturing process, such as in marketing and customer service.

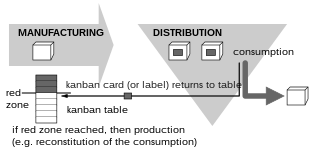

Kanban is a scheduling system for lean manufacturing. Taiichi Ohno, an industrial engineer at Toyota, developed kanban to improve manufacturing efficiency. The system takes its name from the cards that track production within a factory. Kanban is also known as the Toyota nameplate system in the automotive industry.

Kaizen is a concept referring to business activities that continuously improve all functions and involve all employees from the CEO to the assembly line workers. Kaizen also applies to processes, such as purchasing and logistics, that cross organizational boundaries into the supply chain. It has been applied in healthcare, psychotherapy, life coaching, government, manufacturing, and banking.

The Toyota Production System (TPS) is an integrated socio-technical system, developed by Toyota, that comprises its management philosophy and practices. The TPS is a management system that organizes manufacturing and logistics for the automobile manufacturer, including interaction with suppliers and customers. The system is a major precursor of the more generic "lean manufacturing". Taiichi Ohno and Eiji Toyoda, Japanese industrial engineers, developed the system between 1948 and 1975.

Poka-yoke is a Japanese term that means "mistake-proofing" or "error prevention". It is also sometimes referred to as a forcing function or a behavior-shaping constraint.

5S is a workplace organization method that uses a list of five Japanese words: seiri (整理), seiton (整頓), seisō (清掃), seiketsu (清潔), and shitsuke (躾). These have been translated as 'sort', 'set in order', 'shine', 'standardize', and 'sustain'. The list describes how to organize a work space for efficiency and effectiveness by identifying and sorting the items used, maintaining the area and items, and sustaining the new organizational system. The decision-making process usually comes from a dialogue about standardization, which builds understanding among employees of how they should do the work.

Shigeo Shingo was a Japanese industrial engineer who was considered as the world’s leading expert on manufacturing practices and the Toyota Production System.

Muda is a Japanese word meaning "futility", "uselessness", or "wastefulness", and is a key concept in lean process thinking such as in the Toyota Production System (TPS), denoting one of three types of deviation from optimal allocation of resources. The other types are known by the Japanese terms mura ("unevenness") and muri ("overload"). Waste in this context refers to the wasting of time or resources rather than wasteful by-products and should not be confused with waste reduction.

Single-minute digit exchange of die (SMED) is one of the many lean production methods for reducing inefficiencies in a manufacturing process. It provides a rapid and efficient way of converting a manufacturing process from running the current product to running the next product. This is key to reducing production lot sizes, and reducing uneven flow (Mura), production loss, and output variability.

Genba is a Japanese term meaning "the actual place". Japanese detectives call the crime scene genba, and Japanese TV reporters may refer to themselves as reporting from genba. In business, genba refers to the place where value is created; in manufacturing, the genba is the factory floor. It can be any "site" such as a construction site, sales floor or where the service provider interacts directly with the customer.

Ohno Taiichi was a Japanese industrial engineer and businessman. He is considered to be the father of the Toyota Production System, which inspired Lean Manufacturing in the U.S. He devised the seven wastes as part of this system. He wrote several books about the system, including Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production.

Autonomation describes a feature of machine design to effect the principle of jidoka (自働化)(じどうか jidouka), used in the Toyota Production System (TPS) and lean manufacturing. It may be described as "intelligent automation" or "automation with a human touch". This type of automation implements some supervisory functions rather than production functions. At Toyota, this usually means that if an abnormal situation arises, the machine stops and the worker will stop the production line. It is a quality control process that applies the following four principles:

- Detect the abnormality.

- Stop.

- Fix or correct the immediate condition.

- Investigate the root cause and install a countermeasure.

Value-stream mapping, also known as material- and information-flow mapping, is a lean-management method for analyzing the current state and designing a future state for the series of events that take a product or service from the beginning of the specific process until it reaches the customer. A value stream map is a visual tool that displays all critical steps in a specific process and easily quantifies the time and volume taken at each stage. Value stream maps show the flow of both materials and information as they progress through the process.

Cellular manufacturing is a process of manufacturing which is a subsection of just-in-time manufacturing and lean manufacturing encompassing group technology. The goal of cellular manufacturing is to move as quickly as possible, make a wide variety of similar products, while making as little waste as possible. Cellular manufacturing involves the use of multiple "cells" in an assembly line fashion. Each of these cells is composed of one or multiple different machines which accomplish a certain task. The product moves from one cell to the next, each station completing part of the manufacturing process. Often the cells are arranged in a "U-shape" design because this allows for the overseer to move less and have the ability to more readily watch over the entire process. One of the biggest advantages of cellular manufacturing is the amount of flexibility that it has. Since most of the machines are automatic, simple changes can be made very rapidly. This allows for a variety of scaling for a product, minor changes to the overall design, and in extreme cases, entirely changing the overall design. These changes, although tedious, can be accomplished extremely quickly and precisely.

Norman Bodek was a teacher, consultant, author and publisher who published over 100 Japanese management books in English, including the works of Taiichi Ohno and Dr. Shigeo Shingo. He taught a course on "The Best of Japanese Management Practices" at Portland State University. Bodek created the Shingo Prize with Dr. Vern Beuhler at Utah State University. He was elected to Industry Week's Manufacturing Hall of Fame and founded Productivity Press. He was also the President of PCS Press. He died on December 9, 2020, at the age of 88.

Lean dynamics is a business management practice that emphasizes the same primary outcome as lean manufacturing or lean production of eliminating wasteful expenditure of resources. However, it is distinguished by its different focus of creating a structure for accommodating the dynamic business conditions that cause these wastes to accumulate in the first place.

Lean product development (LPD) is an approach to product development that specializes in minimizing waste. Other core principles include putting people over the product and creating new values in services and physical products. This method of product development has been adopted by companies such as Toyota

Akira Kōdate (高達秋良、こうだて・あきら) was born in Kanagawa District, Japan on 6 October 1925. He is an engineer and a Japanese business manager, considered one of the greatest international experts in R&D and production management, as well as a master of lean thinking-related methodologies. Since 1953, he has been working as a consultant with the Japan Management Association (JMA) and JMA Consultants Inc, where he works as a principal consultant and technical advisor.

Design for lean manufacturing is a process for applying lean concepts to the design phase of a system, such as a complex product or process. The term describes methods of design in lean manufacturing companies as part of the study of Japanese industry by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. At the time of the study, the Japanese automakers were outperforming the American counterparts in speed, resources used in design, and design quality. Conventional mass-production design focuses primarily on product functions and manufacturing costs; however, design for lean manufacturing systematically widens the design equation to include all factors that will determine a product's success across its entire value stream and life-cycle. One goal is to reduce waste and maximize value, and other goals include improving the quality of the design and the reducing the time to achieve the final solution. The method has been used in architecture, healthcare, product development, processes design, information technology systems, and even to create lean business models. It relies on the definition and optimization of values coupled with the prevention of wastes before they enter the system. Design for lean manufacturing is system design.

Gwendolyn Galsworth is the American president and founder of Visual Thinking Inc and an author, researcher, teacher, consultant, publisher and thought leader in the field of visuality in the workplace and visual management. Her books, which have won multiple Shingo Prize awards in the Research and Professional Publication category, focus on conceptualizing and codifying workplace visuality into a single, comprehensive framework of knowledge and know-how called the "visual workplace."

References

- 1 2 Galsworth, Gwendolyn (1997) Visual Systems: Harnessing the Power of a Visual Workplace AMACOM ISBN 978-0814403204

- ↑ Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices Retrieved on 22 June 2016.

- ↑ Wayfinding & Signing Guidelines for Airport Terminals Retrieved 23 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Hirano, H. (1995) 5 Pillars of the Visual Workplace, Productivity Press ISBN 978-1563270475

- ↑ Hall, Robert W. (1983). Zero Inventories, Homewood, Ill., Dow Jones-Irwin ISBN 978-0870944611

- ↑ Hirano, H.(1988) JIT Factory, ISBN 978-0870944611 Productivity Press

- 1 2 Suzaki, Kiyoshi (1987) The New Manufacturing Challenge The Free Press ISBN 978-1451697551

- ↑ Greif, Michel (1997) The Visual Factory Productivity Press ISBN 978-0915299676

- ↑ Shingo, Shigeo (1986) Zero Quality Control Productivity Press ISBN 978-0915299072

- ↑ Galsworth, Gwendolyn (2005) Visual Workplace, Visual Thinking, Visual-Lean Enterprise Press ISBN 978-1932516012

- ↑ Galsworth, Gwendolyn (2011) Work that Makes Sense: Operator-Led Visuality Visual-Lean Press ISBN 978-1932516302

- ↑ Don't Just Talk About Change, Show It. Retrieved 23 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Raab, Christian The Library as Visual Workplace Retrieved Aug 2016.

- ↑ Graban, Mark (2012) Lean Hospitals Productivity Press ISBN 9781439870433