Related Research Articles

Antiviral drugs are a class of medication used for treating viral infections. Most antivirals target specific viruses, while a broad-spectrum antiviral is effective against a wide range of viruses. Antiviral drugs are a class of antimicrobials, a larger group which also includes antibiotic, antifungal and antiparasitic drugs, or antiviral drugs based on monoclonal antibodies. Most antivirals are considered relatively harmless to the host, and therefore can be used to treat infections. They should be distinguished from virucides, which are not medication but deactivate or destroy virus particles, either inside or outside the body. Natural virucides are produced by some plants such as eucalyptus and Australian tea trees.

Virus classification is the process of naming viruses and placing them into a taxonomic system similar to the classification systems used for cellular organisms.

Defective interfering particles (DIPs), also known as defective interfering viruses, are spontaneously generated virus mutants in which a critical portion of the particle's genome has been lost due to defective replication or non-homologous recombination. The mechanism of their formation is presumed to be as a result of template-switching during replication of the viral genome, although non-replicative mechanisms involving direct ligation of genomic RNA fragments have also been proposed. DIPs are derived from and associated with their parent virus, and particles are classed as DIPs if they are rendered non-infectious due to at least one essential gene of the virus being lost or severely damaged as a result of the defection. A DIP can usually still penetrate host cells, but requires another fully functional virus particle to co-infect a cell with it, in order to provide the lost factors.

Orthomyxoviridae is a family of negative-sense RNA viruses. It includes seven genera: Alphainfluenzavirus, Betainfluenzavirus, Gammainfluenzavirus, Deltainfluenzavirus, Isavirus, Thogotovirus, and Quaranjavirus. The first four genera contain viruses that cause influenza in birds and mammals, including humans. Isaviruses infect salmon; the thogotoviruses are arboviruses, infecting vertebrates and invertebrates. The Quaranjaviruses are also arboviruses, infecting vertebrates (birds) and invertebrates (arthropods).

Antigenic drift is a kind of genetic variation in viruses, arising from the accumulation of mutations in the virus genes that code for virus-surface proteins that host antibodies recognize. This results in a new strain of virus particles that is not effectively inhibited by the antibodies that prevented infection by previous strains. This makes it easier for the changed virus to spread throughout a partially immune population. Antigenic drift occurs in both influenza A and influenza B viruses.

The year 1952 in science and technology involved some significant events, listed below.

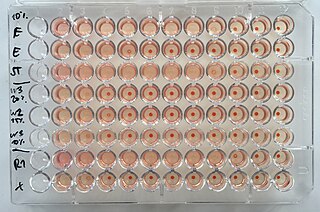

The hemagglutination assay or haemagglutination assay (HA) and the hemagglutination inhibition assay were developed in 1941–42 by American virologist George Hirst as methods for quantifying the relative concentration of viruses, bacteria, or antibodies.

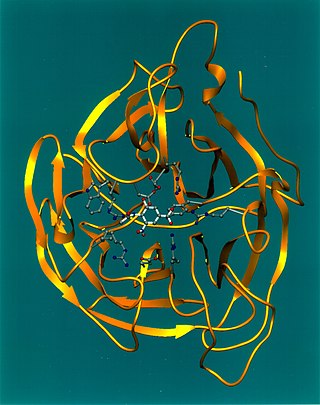

Exo-α-sialidase is a glycoside hydrolase that cleaves the glycosidic linkages of neuraminic acids:

Virus-like particles (VLPs) are molecules that closely resemble viruses, but are non-infectious because they contain no viral genetic material. They can be naturally occurring or synthesized through the individual expression of viral structural proteins, which can then self assemble into the virus-like structure. Combinations of structural capsid proteins from different viruses can be used to create recombinant VLPs. Both in-vivo assembly and in-vitro assembly have been successfully shown to form virus-like particles. VLPs derived from the Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and composed of the small HBV derived surface antigen (HBsAg) were described in 1968 from patient sera. VLPs have been produced from components of a wide variety of virus families including Parvoviridae, Retroviridae, Flaviviridae, Paramyxoviridae and bacteriophages. VLPs can be produced in multiple cell culture systems including bacteria, mammalian cell lines, insect cell lines, yeast and plant cells.

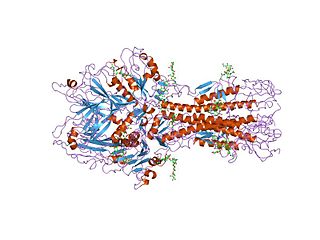

Hemagglutinin esterase (HEs) is a glycoprotein that certain enveloped viruses possess and use as an invading mechanism. HEs helps in the attachment and destruction of certain sialic acid receptors that are found on the host cell surface. Viruses that possess HEs include influenza C virus, toroviruses, and coronaviruses of the subgenus Embecovirus. HEs is a dimer transmembrane protein consisting of two monomers, each monomer is made of three domains. The three domains are: membrane fusion, esterase, and receptor binding domains.

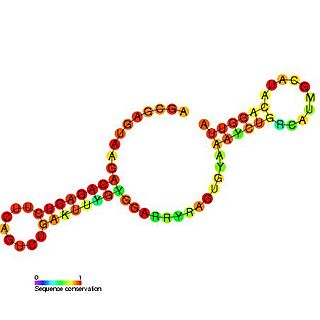

The Infectious bronchitis virus D-RNA is an RNA element known as defective RNA or D-RNA. This element is thought to be essential for viral replication and efficient packaging of avian infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) particles.

Tombus virus defective interfering (DI) RNA region 3 is an important cis-regulatory region identified in the 3' UTR of Tombusvirus defective interfering particles (DI).

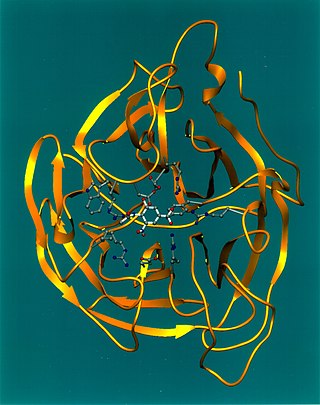

Viral neuraminidase is a type of neuraminidase found on the surface of influenza viruses that enables the virus to be released from the host cell. Neuraminidases are enzymes that cleave sialic acid groups from glycoproteins. Viral neuraminidase was discovered by Alfred Gottschalk at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in 1957. Neuraminidase inhibitors are antiviral agents that inhibit influenza viral neuraminidase activity and are of major importance in the control of influenza.

Virus quantification is counting or calculating the number of virus particles (virions) in a sample to determine the virus concentration. It is used in both research and development (R&D) in academic and commercial laboratories as well as in production situations where the quantity of virus at various steps is an important variable that must be monitored. For example, the production of virus-based vaccines, recombinant proteins using viral vectors, and viral antigens all require virus quantification to continually monitor and/or modify the process in order to optimize product quality and production yields and to respond to ever changing demands and applications. Other examples of specific instances where viruses need to be quantified include clone screening, multiplicity of infection (MOI) optimization, and adaptation of methods to cell culture.

Reverse genetics is a method in molecular genetics that is used to help understand the function(s) of a gene by analysing the phenotypic effects caused by genetically engineering specific nucleic acid sequences within the gene. The process proceeds in the opposite direction to forward genetic screens of classical genetics. While forward genetics seeks to find the genetic basis of a phenotype or trait, reverse genetics seeks to find what phenotypes are controlled by particular genetic sequences.

Preben Christian Alexander von Magnus was a Danish virologist who is known for his research on influenza, polio vaccination and monkeypox. He gave his name to the Von Magnus phenomenon.

Julius S. Youngner was an American Distinguished Service Professor in the School of Medicine and Department of Microbiology & Molecular Genetics at University of Pittsburgh responsible for advances necessary for development of a vaccine for poliomyelitis and the first intranasal equine influenza vaccine.

Herdis von Magnus was a Danish virologist and polio expert. After working with Jonas Salk, she and her husband directed the first polio vaccination program in Denmark. She also researched encephalitis.

A therapeutic interfering particle is an antiviral preparation that reduces the replication rate and pathogenesis of a particular viral infectious disease. A therapeutic interfering particle is typically a biological agent (i.e., nucleic acid) engineered from portions of the viral genome being targeted. Similar to Defective Interfering Particles (DIPs), the agent competes with the pathogen within an infected cell for critical viral replication resources, reducing the viral replication rate and resulting in reduced pathogenesis. But, in contrast to DIPs, TIPs are engineered to have an in vivo basic reproductive ratio (R0) that is greater than 1 (R0>1). The term "TIP" was first introduced in 2011 based on models of its mechanism-of-action from 2003. Given their unique R0>1 mechanism of action, TIPs exhibit high barriers to the evolution of antiviral resistance and are predicted to be resistance proof. Intervention with therapeutic interfering particles can be prophylactic (to prevent or ameliorate the effects of a future infection), or a single-administration therapeutic (to fight a disease that has already occurred, such as HIV or COVID-19). Synthetic DIPs that rely on stimulating innate antiviral immune responses (i.e., interferon) were proposed for influenza in 2008 and shown to protect mice to differing extents but are technically distinct from TIPs due to their alternate molecular mechanism of action which has not been predicted to have a similarly high barrier to resistance. Subsequent work tested the pre-clinical efficacy of TIPs against HIV, a synthetic DIP for SARS-CoV-2 (in vitro), and a TIP for SARS-CoV-2 (in vivo).

References

- ↑ Kristen Ann Stauffer Thompson (2008). Quantitative Effects of Defective Interfering Virus-like Particles on the Growth and Population Behavior of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-0-549-63757-8.

- ↑ "Preben von Magnus". denstoredanske.dk.

- ↑ Gard, S. (1952). "Studies on the sedimentation of influenza virus". Archiv für die Gesamte Virusforschung. 4 (5): 591–611. doi:10.1007/BF01242026. PMID 14953289. S2CID 21838623.