Related Research Articles

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which at least one is a metal. Unlike chemical compounds with metallic bases, an alloy will retain all the properties of a metal in the resulting material, such as electrical conductivity, ductility, opacity, and luster, but may have properties that differ from those of the pure metals, such as increased strength or hardness. In some cases, an alloy may reduce the overall cost of the material while preserving important properties. In other cases, the mixture imparts synergistic properties to the constituent metal elements such as corrosion resistance or mechanical strength.

Damascus steel is the forged steel of the blades of swords smithed in the Near East from ingots of Wootz steel either imported from Southern India or made in production centres in Sri Lanka or Khorasan, Iran. These swords are characterized by distinctive patterns of banding and mottling reminiscent of flowing water, sometimes in a "ladder" or "rose" pattern. Such blades were reputed to be tough, resistant to shattering, and capable of being honed to a sharp, resilient edge.

A forge is a type of hearth used for heating metals, or the workplace (smithy) where such a hearth is located. The forge is used by the smith to heat a piece of metal to a temperature at which it becomes easier to shape by forging, or to the point at which work hardening no longer occurs. The metal is transported to and from the forge using tongs, which are also used to hold the workpiece on the smithy's anvil while the smith works it with a hammer. Sometimes, such as when hardening steel or cooling the work so that it may be handled with bare hands, the workpiece is transported to the slack tub, which rapidly cools the workpiece in a large body of water. However, depending on the metal type, it may require an oil quench or a salt brine instead; many metals require more than plain water hardening. The slack tub also provides water to control the fire in the forge.

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon with improved strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels, which are resistant to corrosion and oxidation, typically need an additional 11% chromium. Because of its high tensile strength and low cost, steel is used in buildings, infrastructure, tools, ships, trains, cars, bicycles, machines, electrical appliances, furniture, and weapons.

Differential heat treatment is a technique used during heat treating of steel to harden or soften certain areas of an object, creating a difference in hardness between these areas. There are many techniques for creating a difference in properties, but most can be defined as either differential hardening or differential tempering. These were common heat treatment techniques used historically in Europe and Asia, with possibly the most widely known example being from Japanese swordsmithing. Some modern varieties were developed in the twentieth century as metallurgical knowledge and technology rapidly increased.

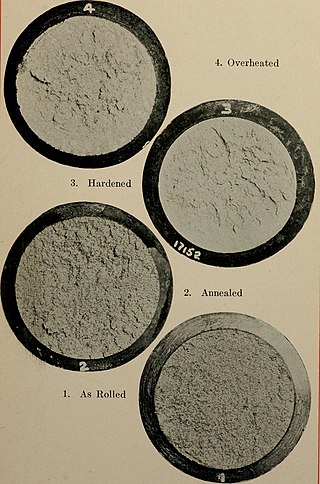

Heat treating is a group of industrial, thermal and metalworking processes used to alter the physical, and sometimes chemical, properties of a material. The most common application is metallurgical. Heat treatments are also used in the manufacture of many other materials, such as glass. Heat treatment involves the use of heating or chilling, normally to extreme temperatures, to achieve the desired result such as hardening or softening of a material. Heat treatment techniques include annealing, case hardening, precipitation strengthening, tempering, carburizing, normalizing and quenching. Although the term heat treatment applies only to processes where the heating and cooling are done for the specific purpose of altering properties intentionally, heating and cooling often occur incidentally during other manufacturing processes such as hot forming or welding.

Cementite (or iron carbide) is a compound of iron and carbon, more precisely an intermediate transition metal carbide with the formula Fe3C. By weight, it is 6.67% carbon and 93.3% iron. It has an orthorhombic crystal structure. It is a hard, brittle material, normally classified as a ceramic in its pure form, and is a frequently found and important constituent in ferrous metallurgy. While cementite is present in most steels and cast irons, it is produced as a raw material in the iron carbide process, which belongs to the family of alternative ironmaking technologies. The name cementite originated from the theory of Floris Osmond and J. Werth, in which the structure of solidified steel consists of a kind of cellular tissue, with ferrite as the nucleus and Fe3C the envelope of the cells. The carbide therefore cemented the iron.

Austenite, also known as gamma-phase iron (γ-Fe), is a metallic, non-magnetic allotrope of iron or a solid solution of iron with an alloying element. In plain-carbon steel, austenite exists above the critical eutectoid temperature of 1000 K (727 °C); other alloys of steel have different eutectoid temperatures. The austenite allotrope is named after Sir William Chandler Roberts-Austen (1843–1902). It exists at room temperature in some stainless steels due to the presence of nickel stabilizing the austenite at lower temperatures.

Carbon steel is a steel with carbon content from about 0.05 up to 2.1 percent by weight. The definition of carbon steel from the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) states:

Tool steel is any of various carbon steels and alloy steels that are particularly well-suited to be made into tools and tooling, including cutting tools, dies, hand tools, knives, and others. Their suitability comes from their distinctive hardness, resistance to abrasion and deformation, and their ability to hold a cutting edge at elevated temperatures. As a result, tool steels are suited for use in the shaping of other materials, as for example in cutting, machining, stamping, or forging.

In materials science, quenching is the rapid cooling of a workpiece in water, gas, oil, polymer, air, or other fluids to obtain certain material properties. A type of heat treating, quenching prevents undesired low-temperature processes, such as phase transformations, from occurring. It does this by reducing the window of time during which these undesired reactions are both thermodynamically favorable and kinetically accessible; for instance, quenching can reduce the crystal grain size of both metallic and plastic materials, increasing their hardness.

Case-hardening or Carburization is the process of introducing carbon to the surface of a low carbon iron or much more commonly low carbon steel object in order to enable the surface to be hardened.

Tempering is a process of heat treating, which is used to increase the toughness of iron-based alloys. Tempering is usually performed after hardening, to reduce some of the excess hardness, and is done by heating the metal to some temperature below the critical point for a certain period of time, then allowing it to cool in still air. The exact temperature determines the amount of hardness removed, and depends on both the specific composition of the alloy and on the desired properties in the finished product. For instance, very hard tools are often tempered at low temperatures, while springs are tempered at much higher temperatures.

Hardening is a metallurgical metalworking process used to increase the hardness of a metal. The hardness of a metal is directly proportional to the uniaxial yield stress at the location of the imposed strain. A harder metal will have a higher resistance to plastic deformation than a less hard metal.

Knife making is the process of manufacturing a knife by any one or a combination of processes: stock removal, forging to shape, welded lamination or investment cast. Typical metals used come from the carbon steel, tool, or stainless steel families. Primitive knives have been made from bronze, copper, brass, iron, obsidian, and flint.

In swordsmithing, hamon (刃文) is a visible effect created on the blade by the hardening process. The hamon is the outline of the hardened zone which contains the cutting edge. Blades made in this manner are known as differentially hardened, with a harder cutting edge than spine. This difference in hardness results from clay being applied on the blade prior to the cooling process (quenching). Less or no clay allows the edge to cool faster, making it harder but more brittle, while more clay allows the center and spine to cool slower, thus retaining its resilience.

Japanese swordsmithing is the labour-intensive bladesmithing process developed in Japan beginning in the sixth century for forging traditionally made bladed weapons (nihonto) including katana, wakizashi, tantō, yari, naginata, nagamaki, tachi, nodachi, ōdachi, kodachi, and ya (arrow).

Austempering is heat treatment that is applied to ferrous metals, most notably steel and ductile iron. In steel it produces a bainite microstructure whereas in cast irons it produces a structure of acicular ferrite and high carbon, stabilized austenite known as ausferrite. It is primarily used to improve mechanical properties or reduce / eliminate distortion. Austempering is defined by both the process and the resultant microstructure. Typical austempering process parameters applied to an unsuitable material will not result in the formation of bainite or ausferrite and thus the final product will not be called austempered. Both microstructures may also be produced via other methods. For example, they may be produced as-cast or air cooled with the proper alloy content. These materials are also not referred to as austempered.

Mangalloy, also called manganese steel or Hadfield steel, is an alloy steel containing an average of around 13% manganese. Mangalloy is known for its high impact strength and resistance to abrasion once in its work-hardened state.

References

- ↑ William Eamon (1996). Science and the Secrets of Nature: Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early Modern Culture. Princeton University Press. pp. 119–120 (cf. pp. 86–87). ISBN 0-691-02602-5.

- ↑ John D. Verhoeven (2007). Steel Metallurgy for the Non-Metallurgist. ASM International. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-61503-056-9.

- ↑ Rolf E. Hummel, Understanding Materials Science: History · Properties · Applications (New York: Springer, 1998), p. 7.

- ↑ Hans Berns (1 February 2013). The History of Hardening. Härterei Gerster AG. pp. 43–5. ISBN 978-3-033-03889-9.

- ↑ William Eamon, Science and the Secrets of Nature: Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early Modern Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), p. 120.