Related Research Articles

Dar es Salaam is the largest city and financial hub of Tanzania. It is also the capital of the Dar es Salaam Region. With a population of over five million people, Dar es Salaam is the largest city in East Africa and the sixth-largest in Africa. Located on the Swahili coast, Dar es Salaam is an important economic center and one of the fastest-growing cities in the world.

Air Tanzania Company Limited (ATCL) (Swahili: Kampuni ya Ndege ya Tanzania) is the flag carrier airline of Tanzania. It is based in Dar es Salaam, with its hub at Julius Nyerere International Airport.

Water privatization is short for private sector participations in the provision of water services and sanitation. Water privatization has a variable history in which its popularity and favorability has fluctuated in the market and politics. One of the common forms of privatization is public–private partnerships (PPPs). PPPs allow for a mix between public and private ownership and/or management of water and sanitation sources and infrastructure. Privatization, as proponents argue, may not only increase efficiency and service quality but also increase fiscal benefits. There are different forms of regulation in place for current privatization systems.

Dar es Salaam Region is one of Tanzania's 31 administrative regions and is located in the east coast of the country. The region covers an area of 1,393 km2 (538 sq mi). The region is comparable in size to the combined land and water areas of the nation state of Mauritius Dar es Salaam Region is bordered to the east by Indian Ocean and it is entirely surrounded by Pwani Region. The Pwani districts that border Dar es Salaam region are Bagamoyo District to the north, Kibaha Urban District to the west, Kisarawe District to the south west and Mkuranga District to the south of the region. The region's seat (capital) is located inside the ward of Ilala. The region is named after the city of Dar es Salaam itself. The region is home to Tanzania's major finance, administration and industries, thus the making it the country's richest region. The region also has the second highest Human Development Index in the country after Mjini Magharibi. According to the 2022 census, the region has a total population of 5,383,728 and national census of 2012 had 4,364,541. The region has the highest population in Tanzania followed by Mwanza Region.

Kinondoni District, officially the Kinondoni Municipal Council is one of five districts of the Dar es Salaam Region of Tanzania. The district is bordered to the north by Bagamoyo District and Kibaha of Pwani Region, to the east by the Indian Ocean, the west by Ubungo District, and to the south by the Ilala District. The district covers an area of 269.5 km2 (104.1 sq mi). The district is comparable in size to the land area of Malta. The administrative seat is Ndugumbi. The district is home to one of the best preserved Medieval Swahili settlements, Kunduchi Ruins, headquarters for the National Muslim Council of Tanzania (BAKWATA) and Makumbusho Village Museum. Considered the cultural center of Dar es Salaam, Kinondoni District is also regarded the birthplace of the musical genre of Singeli. In addition the district is one of two districts in Dar es Salaam that has a National Historic Site, namely the Kunduchi Ruins.The 2012 National Tanzania Census states the population for Kinondoni as 1,775,049.

The human right to water and sanitation (HRWS) is a principle stating that clean drinking water and sanitation are a universal human right because of their high importance in sustaining every person's life. It was recognized as a human right by the United Nations General Assembly on 28 July 2010. The HRWS has been recognized in international law through human rights treaties, declarations and other standards. Some commentators have based an argument for the existence of a universal human right to water on grounds independent of the 2010 General Assembly resolution, such as Article 11.1 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR); among those commentators, those who accept the existence of international ius cogens and consider it to include the Covenant's provisions hold that such a right is a universally binding principle of international law. Other treaties that explicitly recognize the HRWS include the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).

Ubungo District, officially the, Ubungo Municipal Council is one of five districts of the Dar es Salaam Region of Tanzania. The Kinondoni District and Kibaha of the Pwani Region border the district to the north; the Kisarawe District of Pwani Region borders it to the west; and the Ilala District borders the it to the south and east. The district covers an area of 269.4 km2 (104.0 sq mi). The district is comparable in size to the land area of St. Kitts and Nevis. The administrative seat is Kwembe. The district is home to the University of Dar es Salaam, The Magufuli Bus Terminal, the largest in the country, and Pande Game Reserve the largest protected land area in Dar es Salaam Region. In addition, the district is home to the largest natural gas powered power station, the Ubungo Thermal Power Station and the headquarters of the Tanzania Electric Supply Company Limited (TANESCO). The 2012 National Tanzania Census states the population of the district as 845,368.

Dala dala are minibus share taxis in Tanzania. These converted trucks and minibuses are the primary public transportation system in the country. While the name originates from the English word "dollar", they are also referred to as thumni.

Haiti faces key challenges in the water supply and sanitation sector: Notably, access to public services is very low, their quality is inadequate and public institutions remain very weak despite foreign aid and the government's declared intent to strengthen the sector's institutions. Foreign and Haitian NGOs play an important role in the sector, especially in rural and urban slum areas.

Water privatisation in South Africa is a contentious issue, given the history of denial of access to water and persisting poverty. Water privatisation has taken many different forms in South Africa. Since 1996 some municipalities decided to involve the private sector in water and sanitation service provision through short-term management contracts, long-term concessions and contracts for specific services such as wastewater treatment. Most municipalities continue to provide water and sanitation services through public utilities or directly themselves. Suez of France, through its subsidiary Water and Sanitation Services South Africa (WSSA), and Sembcorp of Singapore, through its subsidiary Silulumanzi, are international firms with contracts in South Africa. According to the managing director of Silulumanzi "the South African water market is still in its infancy and municipalities are unsure of how to engage the private sector."

Benjamin Mkapa Stadium also known as Tanzania National Main Stadium is a multi-purpose stadium located in Miburani ward of Temeke District in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. It opened in 2007 and was built adjacent to Uhuru Stadium, the former national stadium. It hosts major football matches such as the Tanzanian Premier League and home matches of the Tanzania national football team.

Water supply and sanitation in Mozambique is characterized by low levels of access to at least basic water sources, low levels of access to at least basic sanitation and mostly poor service quality. In 2007 the government has defined a strategy for water supply and sanitation in rural areas, where 62% of the population lives. In urban areas, water is supplied by informal small-scale providers and by formal providers.

Remunicipalisation commonly refers to the return of previously privatised water supply and sanitation services to municipal authorities. It also encompasses regional or national initiatives.

CRDB Bank Plc is a commercial bank in Tanzania. It is licensed by the Bank of Tanzania, the central bank and national banking regulator. As of September 2022, CRDB Bank was the largest commercial bank in Tanzania.

Water supply and sanitation in Tanzania is characterised by: decreasing access to at least basic water sources in the 2000s, steady access to some form of sanitation, intermittent water supply and generally low quality of service. Many utilities are barely able to cover their operation and maintenance costs through revenues due to low tariffs and poor efficiency. There are significant regional differences and the best performing utilities are Arusha and Tanga.

TIB Development Bank, formerly known as Tanzania Investment Bank (TIB), is a government-owned development bank in Tanzania. The bank is the first development finance institution established by the Government of Tanzania. The activities of TIB are supervised by the Bank of Tanzania, the central bank and national banking regulator. TIB is registered as a Registered Financial Institution.

Although access to water supply and sanitation in sub-Saharan Africa has been steadily improving over the last two decades, the region still lags behind all other developing regions. Access to improved water supply had increased from 49% in 1990 to 68% in 2015, while access to improved sanitation had only risen from 28% to 31% in that same period. Sub-Saharan Africa did not meet the Millennium Development Goals of halving the share of the population without access to safe drinking water and sanitation between 1990 and 2015. There still exists large disparities among sub-Saharan African countries, and between the urban and rural areas.

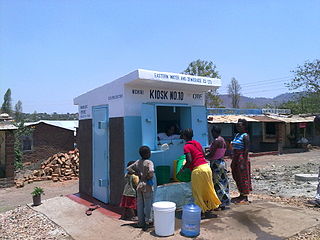

Water kiosks are booths for the sale of tap water. They are common in many countries of Sub-Saharan Africa. Water kiosks exist, among other countries, in Cameroon, Haiti, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia.

Dar es Salaam Rapid Transit also known as UDART is a bus rapid transit system that began operations on 10 May 2016 in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

The World Bank Group (WBG) provides grants, credits and policy analysis to support economic development in Tanzania with a focus on infrastructure and private sector growth. As of 2018, WBG supports 25 active projects with funding of more than $3.95 billion. The WBG provides analytical and technical assistance in coordination with these projects. From 2007-2018 Tanzania maintained real GDP growth averaging 6.8% a year. Growth concentrated in the agricultural and transportation sectors. Complementing this growth, the poverty rate in Tanzania fell from 28.2% in 2012 to 26.9% in 2016. Debate exists over the validity of this growth as development may be unevenly dispersed among different geographic and income groups.

References

- 1 2 Kjellén, Marianne (2006). From public pipes to private hands: water access and distribution in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania (Thesis). Stockholm: Stockholm university, Department of human geography. ISBN 9185445436.

- 1 2 The Guardian: Tanzania wins £3m damages from Biwater subsidiary, 11 January 2008

- ↑ Greenhill, R. and Wekiya, I. (2004). Turning off the taps : donor conditionality and water privatisation in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, London, UK, ActionAid, p. 5

- ↑ Woodhouse, Philip; Muller, Mike (2017). "Water Governance—An Historical Perspective on Current Debates". World Development. 92 (1): 225–241. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.11.014 – via Research Gate.

- ↑ Bartram, Jamie; Brocklehurst, Clarissa; Fisher, Michael; Luyendijk, Rolf; Hossain, Rifat; Wardlaw, Tessa; Gordon, Bruce (2014-08-11). "Global Monitoring of Water Supply and Sanitation: History, Methods and Future Challenges". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 11 (8): 8137–8165. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110808137 . ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 4143854 . PMID 25116635.

- ↑ Husain, Ishrat; Faruqee, Rashid, eds. (1994). Adjustment in Africa: lessons from country case studies. World Bank regional and sectoral studies. Washington, D.C: World Bank. ISBN 978-0-8213-2787-6.

- ↑ World Bank:Dar es Salaam Water Supply and Sanitation Project, accessed on February 3, 2010

- 1 2 3 4 The Guardian:Biwater fails in Tanzanian damages claim, 28 July 2008

- ↑ Greenhill, R. and Wekiya, I. (2004). Turning off the taps : donor conditionality and water privatisation in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, London, UK, ActionAid, p. 3

- ↑ Greenhill, R. and Wekiya, I. (2004). Turning off the taps : donor conditionality and water privatisation in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, London, UK, ActionAid, p. 2

- 1 2 3 The Guardian:Flagship water privatisation fails in Tanzania, 25 May 2005

- 1 2 Kjellén, Marianne (2006). From public pipes to private hands: water access and distribution in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania (Thesis). Stockholm: Stockholm university, Department of human geography. ISBN 9185445436.

- ↑ Greenhill, R. and Wekiya, I. (2004). Turning off the taps : donor conditionality and water privatisation in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, London, UK, ActionAid, p. 2

- ↑ Greenhill, R. and Wekiya, I. (2004). Turning off the taps : donor conditionality and water privatisation in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, London, UK, ActionAid, p. 16

- 1 2 Biwater: Biwater Response to Outcome of ICSID Arbitration, 28 July 2008