Related Research Articles

William Wordsworth was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication Lyrical Ballads (1798).

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner is the longest major poem by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, written in 1797–98 and published in 1798 in the first edition of Lyrical Ballads. Some modern editions use a revised version printed in 1817 that featured a gloss. Along with other poems in Lyrical Ballads, it is often considered a signal shift to modern poetry and the beginning of British Romantic literature.

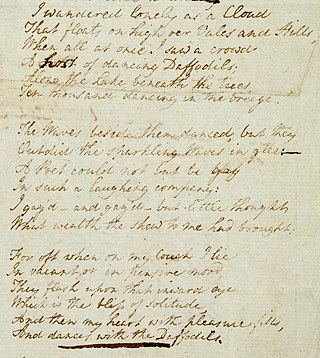

"I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" is a lyric poem by William Wordsworth. It is one of his most popular, and was inspired by a forest encounter on 15 April 1802 that included himself, his younger sister Dorothy and a "long belt" of daffodils. Written in 1804, this 24 line lyric was first published in 1807 in Poems, in Two Volumes, and revised in 1815.

Lyrical Ballads, with a Few Other Poems is a collection of poems by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, first published in 1798 and generally considered to have marked the beginning of the English Romantic movement in literature. The immediate effect on critics was modest, but it became and remains a landmark, changing the course of English literature and poetry. The 1800 edition is famous for the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads, something that has come to be known as the manifesto of Romanticism.

"The Idiot Boy" is a poem written by William Wordsworth, a representative of the Romantic movement in English literature. The poem was composed in spring 1798 and first published in the same year in Lyrical Ballads, a collection of poems written by Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, which is considered to be a turning point in the history of English literature and the Romantic movement. The poem investigates such themes as language, intellectual disability, maternity, emotionality, organisation of experience and "transgression of the natural."

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

"Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood" is a poem by William Wordsworth, completed in 1804 and published in Poems, in Two Volumes (1807). The poem was completed in two parts, with the first four stanzas written among a series of poems composed in 1802 about childhood. The first part of the poem was completed on 27 March 1802 and a copy was provided to Wordsworth's friend and fellow poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who responded with his own poem, "Dejection: An Ode", in April. The fourth stanza of the ode ends with a question, and Wordsworth was finally able to answer it with seven additional stanzas completed in early 1804. It was first printed as "Ode" in 1807, and it was not until 1815 that it was edited and reworked to the version that is currently known, "Ode: Intimations of Immortality".

"Strange fits of passion have I known" is a seven-stanza poem ballad by the English Romantic poet William Wordsworth. Composed during a sojourn in Germany in 1798, the poem was first published in the second edition of Lyrical Ballads (1800). The poem describes the poet's trip to his beloved Lucy's cottage, and his thoughts on the way. Each of its seven stanzas is four lines long and has a rhyming scheme of ABAB. The poem is written in iambic tetrameter and iambic trimeter.

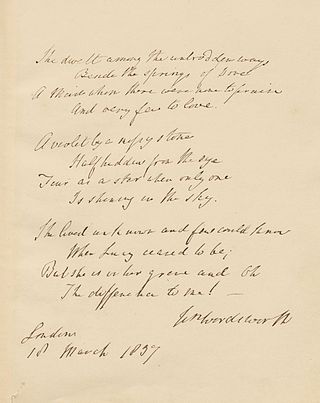

"She Dwelt Among the Untrodden Ways" is a three-stanza poem written by the English Romantic poet William Wordsworth in 1798 when he was 28 years old. The verse was first printed in Lyrical Ballads, 1800, a volume of Wordsworth's and Samuel Taylor Coleridge's poems that marked a climacteric in the English Romantic movement. The poem is the best known of Wordsworth's series of five works which comprise his "Lucy" series, and was a favorite amongst early readers. It was composed both as a meditation on his own feelings of loneliness and loss, and as an ode to the beauty and dignity of an idealized woman who lived unnoticed by all others except by the poet himself. The title line implies Lucy lived unknown and remote, both physically and intellectually. The poet's subject's isolated sensitivity expresses a characteristic aspect of Romantic expectations of the human, and especially of the poet's condition.

The Lucy poems are a series of five poems composed by the English Romantic poet William Wordsworth (1770–1850) between 1798 and 1801. All but one were first published during 1800 in the second edition of Lyrical Ballads, a collaboration between Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge that was both Wordsworth's first major publication and a milestone in the early English Romantic movement. In the series, Wordsworth sought to write unaffected English verse infused with abstract ideals of beauty, nature, love, longing, and death.

William Wordsworth was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their 1798 joint publication, Lyrical Ballads. His early years were dominated by his experience of old Trafford around the Lake District and the English moors. Dorothy Wordsworth, his sister, served as his early companion until their mother's death and their separation when he was sent to school.

The "Matthew" poems are a series of poems, composed by the English Romantic poet William Wordsworth, that describe the character Matthew in Wordsworth's poetry.

"Lucy Gray" is a poem written by William Wordsworth in 1799 and published in his Lyrical Ballads. It describes the death of a young girl named Lucy Gray, who went out one evening into a storm.

"Anecdote for Fathers" is a poem by William Wordsworth first published in his 1798 collection titled Lyrical Ballads, which was co-authored by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. A later version of the poem from 1845 contains a Latin epigraph from Praeparatio evangelica: "Retine vim istam, falsa enim dicam, si coges," which translates as "Restrain that force, for I will tell lies if you compel me."

"I travelled among unknown men" is a love poem completed in April 1801 by the English poet William Wordsworth and originally intended for the Lyrical Ballads anthology, but it was first published in Poems, in Two Volumes in 1807. The third poem of Wordsworth's "Lucy series", "I travelled..." was composed after the poet had spent time living in Germany in 1798. Due to acute homesickness, the lyrics promise that once returned to England, he will never live abroad again. The poet states he now loves England "more and more". Wordsworth realizes that he did not know how much he loved England until he lived abroad and uses this insight as an analogy to understand his unrequited feelings for his beloved, Lucy.

Frost at Midnight is a poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, written in February 1798. Part of the conversation poems, the poem discusses Coleridge's childhood experience in a negative manner and emphasizes the need to be raised in the countryside. The poem expresses hope that Coleridge's son, Hartley, would be able to experience a childhood that his father could not and become a true "child of nature". The view of nature within the poem has a strong Christian element in that Coleridge believed that nature represents a physical presence of God's word and that the poem is steeped in Coleridge's understanding of Neoplatonism. Frost at Midnight has been well received by critics, and is seen as the best of the conversation poems.

The Nightingale: A Conversation Poem is a poem written by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in April 1798. Originally included in the first edition of Lyrical Ballads, which he published with William Wordsworth, the poem disputes the traditional idea that nightingales are connected to the idea of melancholy. Instead, the nightingale represents to Coleridge the experience of nature. Midway through the poem, the narrator stops discussing the nightingale in order to describe a mysterious female and a gothic scene. After the narrator is returned to his original train of thought by the nightingale's song, he recalls a moment when he took his crying son out to see the Moon, which immediately filled the child with joy. Critics have found the poem either decent with little complaint or as one of his better poems containing beautiful lines.

"Dejection: An Ode" is a poem written by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1802 and was published the same year in The Morning Post, a London daily newspaper. The poem in its original form was written to Sara Hutchinson, a woman who was not his wife, and discusses his feelings of love for her. The various versions of the poem describe Coleridge's inability to write poetry and living in a state of paralysis, but published editions remove his personal feelings and mention of Hutchinson.

"A slumber did my spirit seal" is a poem that was written by William Wordsworth in 1798 and first published in volume II of the 1800 edition of Lyrical Ballads. It is part of a series of poems written about a mysterious woman named Lucy, whom scholars have not been able to identify and are not sure whether she was real or fictional. Although the name Lucy is not directly mentioned in the poem, scholars nevertheless believe it to be part of the "Lucy poems" due to the poem's placement in Lyrical Ballads.

"Poor Susan" is a lyric poem by William Wordsworth composed at Alfoxden in 1797. It was first published in the collection Lyrical Ballads in 1798. It is written in anapestic tetrameter.

References

- ↑ Moorman 1968 p. 232

- ↑ Moorman 1968 p. 237

- 1 2 Wordsworth 1907 p. 293

- ↑ Moorman 1968 pp. 369–371

- ↑ Moorman 1968 pp. 372–373

- ↑ Bateson 1954 p. 49

- ↑ "St Mary and All Saints Church, Conwy" . Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ Hartman 1967 p. 144

- ↑ Wordsworth 1802 pp. xxx, xiii

- ↑ Hartman 1967 pp. 143–145

- ↑ Susan Wolfson, The Questioning Presence: Wordsworth, Keats, and the Interrogative Mode in Romantic Poetry, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986) 50.

- ↑ Frances Ferguson, Solitude and the Sublime: Romanticism and the Aesthetics of Individuation (New York: Routledge, 1992), 164.

- ↑ Hollis Robbins, "William Wordsworth's 'We Are Seven' and the First British Census." ELN 48.2, Fall/Winter 2010.

- ↑ Aaron Fogel, "Wordsworth's "We Are Seven" and Crabbe's The Parish Register: Poetry and the Anti-Census, Studies in Romanticism 48 (2009)

- ↑ Heather Glen, "'We Are Seven' in the 1790s," Grasmere 2012: Selected Papers from the Wordsworth Summer Conference, (Penrith: Humanities Ebooks, 2012

- ↑ "William Wordsworth's 'We Are Seven' and the First British Census." ELN 48.2, Fall/Winter 2010.

- ↑ Peter De Bolla, Art Matters (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2001)

- ↑ Maureen N. McLane, Romanticism and the Human Sciences: Poetry, Population, and the Discourse of the Species (Cambridge University Press, 2000) 53–62.

- ↑ Mahoney 1997 pp. 75–76