The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, began on 22 January 1905. A wave of mass political and social unrest then began to spread across the vast areas of the Russian Empire. The unrest was directed primarily against the Tsar, the nobility, and the ruling class. It included worker strikes, peasant unrest, and military mutinies. In response to the public pressure, Tsar Nicholas II was forced to go back on his earlier authoritarian stance and enact some reform. This took the form of establishing the State Duma, the multi-party system, and the Russian Constitution of 1906. Despite popular participation in the Duma, the parliament was unable to issue laws of its own, and frequently came into conflict with Nicholas. The Duma's power was limited and Nicholas continued to hold the ruling authority. Furthermore, he could dissolve the Duma, which he did three times in order to get rid of the opposition.

Battleship Potemkin, sometimes rendered as Battleship Potyomkin, is a 1925 Soviet silent epic film produced by Mosfilm. Directed and co-written by Sergei Eisenstein, it presents a dramatization of the mutiny that occurred in 1905 when the crew of the Russian battleship Potemkin rebelled against its officers.

October: Ten Days That Shook the World is a 1928 Soviet silent historical film written and directed by Sergei Eisenstein and Grigori Aleksandrov. It is a celebratory dramatization of the 1917 October Revolution commissioned for the tenth anniversary of the event. Originally released in the Soviet Union as October, the film was re-edited and released internationally as Ten Days That Shook The World, after John Reed's popular 1919 book on the Revolution.

Admiral Mikhail Petrovich Lazarev was a Russian fleet commander and an explorer.

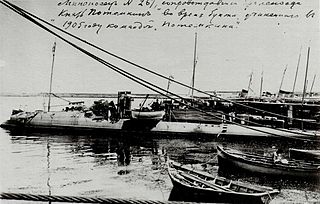

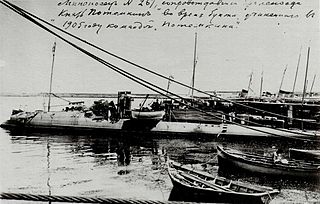

The Russian battleship Potemkin was a pre-dreadnought battleship built for the Imperial Russian Navy's Black Sea Fleet. She became famous during the Revolution of 1905, when her crew mutinied against their officers. This event later formed the basis for Sergei Eisenstein's 1925 silent film Battleship Potemkin.

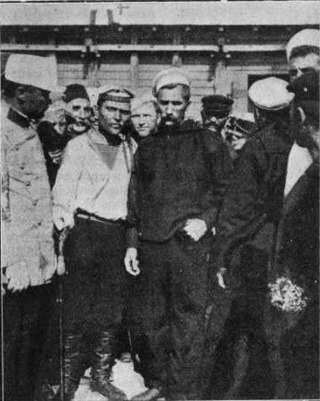

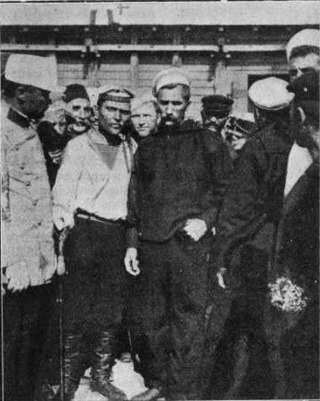

Pyotr Petrovich Schmidt was one of the leaders of the Sevastopol Uprising during the Russian Revolution of 1905.

Rostislav was a pre-dreadnought battleship built by the Nikolaev Admiralty Shipyard in the 1890s for the Black Sea Fleet of the Imperial Russian Navy. She was conceived as a small, inexpensive coastal defence ship, but the Navy abandoned the concept in favor of a compact, seagoing battleship with a displacement of 8,880 long tons (9,022 t). Poor design and construction practices increased her actual displacement by more than 1,600 long tons (1,626 t). Rostislav became the world's first capital ship to burn fuel oil, rather than coal. Her combat ability was compromised by the use of 10-inch (254 mm) main guns instead of the de facto Russian standard of 12 inches (305 mm).

Dvenadsat Apostolov was a pre-dreadnought battleship built for the Imperial Russian Navy, the sole ship of her class. She entered service in 1893 with the Black Sea Fleet, but was not fully ready until 1894. The ship participated in the failed attempt to recapture the mutinous battleship Potemkin in 1905. Decommissioned and disarmed in 1911, Dvenadsat Apostolov became an immobile submarine depot ship the following year. The ship was captured by the Germans in 1918 in Sevastopol and was handed over to the Allies in December. Lying immobile in Sevastopol, she was captured by both sides in the Russian Civil War before she was abandoned when the White Russians evacuated the Crimea in 1920. Dvenadsat Apostolov was used as a stand-in for the title ship during the 1925 filming of The Battleship Potemkin before she was finally scrapped in 1931.

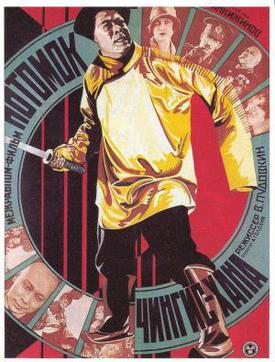

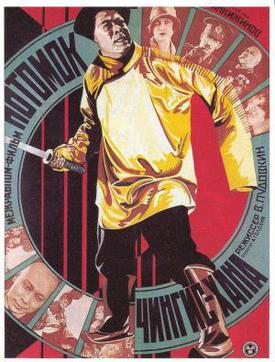

Storm over Asia is a 1928 Soviet propaganda film directed by Vsevolod Pudovkin, written by Osip Brik and Ivan Novokshonov, and starring Valéry Inkijinoff. It is the final film in Pudovkin's "revolutionary trilogy", alongside Mother (1926) and The End of St. Petersburg (1927).

Grigory Mykytovych Vakulenchuk was a Ukrainian sailor in the Imperial Russian Navy. He was born in Velyki Korovyntsi. He served on the Russian battleship Potemkin.

Georgii Pobedonosets was a battleship built for the Imperial Russian Navy, the fourth and final ship of the Ekaterina II class. She was, however, only a half-sister to the others as her armor scheme was different and she was built much later than the earlier ships. She participated in the pursuit of the mutinous battleship Potemkin in June 1905, but her crew mutinied themselves. However, loyal crew members regained control of the ship the next day and they ran her aground when Potemkin threatened to fire on her if she left Odessa harbor. She was relegated to second-line duties in 1908. She fired on SMS Goeben during her bombardment of Sevastopol in 1914, but spent most of the war serving as a headquarters ship in Sevastopol. She was captured by both sides during the Russian Civil War, but ended up being towed to Bizerte by the fleeing White Russians where she was eventually scrapped.

Afanasy Nikolayevich Matushenko, was a non-commissioned officer in the Russian Black Sea Fleet, revolutionary socialist, and ringleader of the mutiny on the Russian battleship Potemkin.

Ippolit Giliarovsky was the second in command as a frigate captain of the battleship Potemkin during the mutiny. He held key responsibility for the uprising due to his brutal treatment of the sailors. Giliarovsky was killed during the mutiny.

The Russian torpedo boat Ismail was the first ship in the Russian Navy's Black Sea Fleet to join the mutiny of the battleship Potemkin in 1905. The torpedo boat was Potemkin's escort and had on board a complement of three officers, 20 sailors, two 37 mm guns and two torpedo launchers. Ismail brought rotten meat aboard Potemkin in June 1905, an incident which sparked the mutiny. The commander of Ismail was Lieutenant Pyotr Klodt von Yurgensburg, a 41-year-old Russian nobleman.

Alexey Mikhailovich Schastny (1881–1918) was a Russian and Soviet naval commander. He commanded the Baltic Fleet during the Ice Cruise. He was executed on the order of the Soviet judge M. Karklin in June 1918 on the charges of organizing a dictatorship of the Baltic Fleet in separation from the Soviet Union.

A Slave of Love is a 1976 Soviet romantic comedy-drama film directed by Nikita Mikhalkov and written by Friedrich Gorenstein and Andrey Konchalovskiy. It stars Elena Solovey, Rodion Nakhapetov and Aleksandr Kalyagin. The film is about a silent film actress, Olga Voznesenskaya, whose films are so admired by the revolutionaries that they risk capture to see her on the screen. The character of Olga was inspired by Vera Kholodnaya.

Nina Agadzhanova–Shutko was a Soviet revolutionary, screenwriter, and film director. She is most widely recognized for writing The Year 1905, the original screenplay from which Battleship Potemkin was created.

A Spectre Haunts Europe is a 1923 Soviet silent horror film directed by Vladimir Gardin and written by Georgi Tasin. It was made by the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic's production company VUFKU. It is based on Edgar Allan Poe's 1842 short story The Masque of the Red Death. The film features a massacre on the Odessa Steps which may have served as an inspiration for the more famous scene in Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin. The film's sets were designed by the art director Vladimir Yegorov. Cameraman Boris Zavalev filmed the movie on location in Crimea. Many reference sources list the film as 1921, but it was actually only released in 1922.

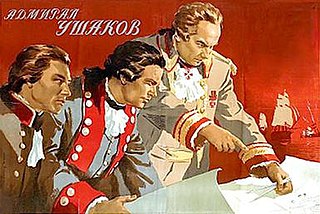

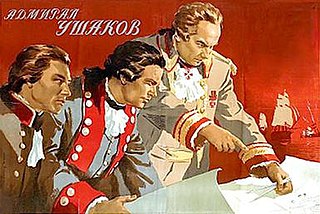

Admiral Ushakov is a 1953 Soviet historical war film directed by Mikhail Romm and starring Ivan Pereverzev, Boris Livanov and Sergei Bondarchuk.