The insanity defense, also known as the mental disorder defense, is an affirmative defense by excuse in a criminal case, arguing that the defendant is not responsible for their actions due to a psychiatric disease at the time of the criminal act. This is contrasted with an excuse of provocation, in which the defendant is responsible, but the responsibility is lessened due to a temporary mental state. It is also contrasted with the justification of self defense or with the mitigation of imperfect self-defense. The insanity defense is also contrasted with a finding that a defendant cannot stand trial in a criminal case because a mental disease prevents them from effectively assisting counsel, from a civil finding in trusts and estates where a will is nullified because it was made when a mental disorder prevented a testator from recognizing the natural objects of their bounty, and from involuntary civil commitment to a mental institution, when anyone is found to be gravely disabled or to be a danger to themself or to others.

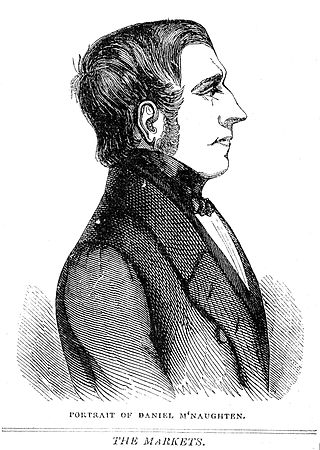

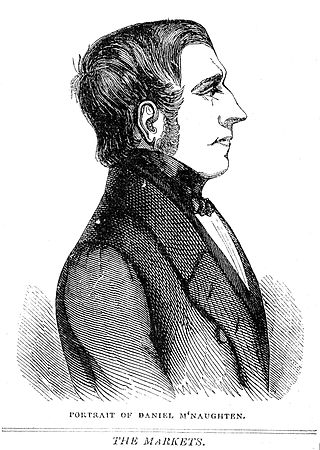

The M'Naghten rule is any variant of the 1840s jury instruction in a criminal case when there is a defence of insanity:

that every man is to be presumed to be sane, and ... that to establish a defence on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.

Prima facie is a Latin expression meaning at first sight or based on first impression. The literal translation would be 'at first face' or 'at first appearance', from the feminine forms of primus ('first') and facies ('face'), both in the ablative case. In modern, colloquial and conversational English, a common translation would be "on the face of it".

Criminal procedure is the adjudication process of the criminal law. While criminal procedure differs dramatically by jurisdiction, the process generally begins with a formal criminal charge with the person on trial either being free on bail or incarcerated, and results in the conviction or acquittal of the defendant. Criminal procedure can be either in form of inquisitorial or adversarial criminal procedure.

In a legal dispute, one party has the burden of proof to show that they are correct, while the other party had no such burden and is presumed to be correct. The burden of proof requires a party to produce evidence to establish the truth of facts needed to satisfy all the required legal elements of the dispute.

In criminal law, diminished responsibility is a potential defense by excuse by which defendants argue that although they broke the law, they should not be held fully criminally liable for doing so, as their mental functions were "diminished" or impaired.

An affirmative defense to a civil lawsuit or criminal charge is a fact or set of facts other than those alleged by the plaintiff or prosecutor which, if proven by the defendant, defeats or mitigates the legal consequences of the defendant's otherwise unlawful conduct. In civil lawsuits, affirmative defenses include the statute of limitations, the statute of frauds, waiver, and other affirmative defenses such as, in the United States, those listed in Rule 8 (c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. In criminal prosecutions, examples of affirmative defenses are self defense, insanity, entrapment and the statute of limitations.

The presumption of innocence is a legal principle that every person accused of any crime is considered innocent until proven guilty. Under the presumption of innocence, the legal burden of proof is thus on the prosecution, which must present compelling evidence to the trier of fact. If the prosecution does not prove the charges true, then the person is acquitted of the charges. The prosecution must in most cases prove that the accused is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. If reasonable doubt remains, the accused must be acquitted. The opposite system is a presumption of guilt.

A will contest, in the law of property, is a formal objection raised against the validity of a will, based on the contention that the will does not reflect the actual intent of the testator or that the will is otherwise invalid. Will contests generally focus on the assertion that the testator lacked testamentary capacity, was operating under an insane delusion, or was subject to undue influence or fraud. A will may be challenged in its entirety or in part.

In the common law tradition, testamentary capacity is the legal term of art used to describe a person's legal and mental ability to make or alter a valid will. This concept has also been called sound mind and memory or disposing mind and memory.

Insane delusion is the legal term of art in the common law tradition used to describe a false conception of reality that a testator of a will adheres to against all reason and evidence to the contrary. A will made by a testator suffering from an insane delusion that affects the provisions made in the will may fail in whole or in part. Only the portion of the will caused by the insane delusion fails, including potentially the entire will. Will contests often involve claims that the testator was suffering from an insane delusion.

In criminal law, automatism is a rarely used criminal defence. It is one of the mental condition defences that relate to the mental state of the defendant. Automatism can be seen variously as lack of voluntariness, lack of culpability (unconsciousness) or excuse. Automatism means that the defendant was not aware of his or her actions when making the particular movements that constituted the illegal act.

Actual innocence is a special standard of review in legal cases to prove that a charged defendant did not commit the crimes that they were accused of, which is often applied by appellate courts to prevent a miscarriage of justice.

Clark v. Arizona, 548 U.S. 735 (2006), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court upheld the constitutionality of the insanity defense used by Arizona.

Settled insanity is defined as a permanent or "settled" condition caused by long-term substance abuse and differs from the temporary state of intoxication. In some United States jurisdictions "settled insanity" can be used as a basis for an insanity defense, even though voluntary intoxication cannot, if the "settled insanity" negates one of the required elements of the crime such as malice aforethought. However, U.S. federal and state courts have differed in their interpretations of when the use of "settled insanity" is acceptable as an insanity defense and also over what is included in the concept of "settled insanity".

Rev. Eliezer Williams was a Welsh clergyman and genealogist, who served the Earl of Galloway as a family tutor and genealogical researcher.

Ward v. Tesco Stores Ltd. [1976] 1 WLR 810, is an English tort law case concerning the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur. It deals with the law of negligence and it set an important precedent in so called "trip and slip" cases which are a common occurrence.

Insanity in English law is a defence to criminal charges based on the idea that the defendant was unable to understand what he was doing, or, that he was unable to understand that what he was doing was wrong.

United States federal laws governing offenders with mental diseases or defects provide for the evaluation and handling of defendants who are suspected of having mental diseases or defects. The laws were completely revamped by the Insanity Defense Reform Act in the wake of the John Hinckley Jr. verdict.

Leland v. Oregon, 343 U.S. 790 (1952), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court upheld the constitutionality of placing the burden of persuasion on the defendant when they argue an insanity defense in a criminal trial. This differed from previous federal common law established in Davis v. United States, in which the court held that if the defense raised an insanity defense, the prosecution must prove sanity beyond a reasonable doubt, but Davis was not a United States constitutional ruling, so only limited federal cases, but not state cases. Oregon had a very high burden on defense, that insanity be proved beyond a reasonable doubt. At that time, twenty other states also placed the burden of persuasion on the defense for an insanity defense.