This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations .(December 2019) |

The white woman of Gippsland, or the captive woman of Gippsland, was supposedly a European woman rumoured to have been held against her will by Aboriginal Gunaikurnai people in the Gippsland region of Australia in the 1840s. Her supposed plight excited searches and much speculation at the time, though nothing to put her existence beyond the level of rumour was ever found.

Contents

The source of the white woman rumour was a letter written by Angus McMillan, which was published in the Sydney Morning Herald on 28 December 1840. The letter described the scene of an Aboriginal camp near Port Albert, where the Aboriginal people had hurriedly vacated on his group's approach. The group had found European items, including female attire. He reported that there was blood on clothing and that it was supposedly 'human blood'. He reported that they found a dead two-year-old European child. He also wrote that he later recollected that there was a white European woman among the Aboriginal people, who had earlier run away from the camp. [1]

We call the particular attention of parties who have friends and relatives in the neighbourhood of Port Phillip, to the following letter from a station at Gipps Land or South Caledonia, the country that lies between Cape Howe and Port Phillip. It appears quite clear that murder has been committed, and perhaps the publication of the list of property found may assist in identifying the murdered party. The letter was placed in our possession several days since, but was unfortunately mislaid:—

"November 15.—Started from our station to discover a road to the coast with the view of running along the Long Bench to Shoal inlet, thence to Corner inlet,—same evening, came upon the camp of twenty-five black natives, chiefly women, who all ran away on our near approach, leaving every thing they had behind them excepting some of their spears. We then searched their camp, where we found European articles as underneath described, viz:—Several check-shirts, cord and moleskin trousers, all besmeared with human blood; one German frock, two pea-jackets, new brown Macintosh cloak, also stained with blood; several pieces of women's wearing apparel, namely, prints and merinos; a large lock of brown hair, evidently that of a European women, one child's white frock with brown velvet band, five hand towels, one of which was marked R. Jamieson No. 12, one blue silk purse, silver tassels and slides, containing seven shillings and sixpence British money, one woman's thimble, two large parcels of silk sewing thread, various colours, 10 new English blankets perfectly clean, shoemakers awls, bees' wax, blacksmith's pinchers and cold chisel, one bridle bit, which had been recently used, as the grass was quite fresh on it; the tube of a thermometer, broken looking glass, bottles of all descriptions, two of which had castor oil in them, one sealskin cap, one musket and some shot, one broad tomahawk, some London, Glasgow, and Aberdeen newspapers, printed in 1837 and 1838. One pewter two gallon measure, one ditto hand basin, one large tin camp kettle, two children's copy books, one bible printed in Edinburgh, June 1838, one set of the National Loan Fund regulations respecting policies of Life insurance, and blank forms of medical man's certificate for effecting the same. Enclosed in three kangaroo skin bags we found the dead body of a male child about two years old, which Dr. Arbuckle carefully examined professionally, and discovered beyond doubt its being of European parents; parts of the skin were perfectly white, not being in the least discoloured. We observed the men with shipped spears driving before them the women, one of whom we noticed constantly looking behind her, at us, a circumstance which did not strike us much at the time, but on examining the marks and figures about the largest of the native huts we were immediately impressed with the belief that that unfortunate female is a European—a captive of these ruthless savages. The blacks having come across us the next day in numbers, and our party being composed of four only, we most reluctantly deemed it necessary to return to the station without being enabled to accomplish our object. This was the more painful to our feelings, as we have no doubt whatever but a dreadful massacre of Europeans, men, women and children, has been perpetrated by the aborigines in the immediate vicinity of the spot, whence we were forced to return without being enabled to throw more light on this melancholy catastrophe, than what I have detailed above. "AUGUSTUS McMILLAN."

— Angus McMillan, Supposed Outrage by the Blacks, Sydney Morning Herald (28 December 1840)

McMillan's letter was republished in the Port Phillip Patriot and Melbourne Advertiser on 18 January 1841 [2] and the Tasmanian Weekly Dispatch on 22 January 1841, [3] and the legend entered the public imagination.

Accounts of the woman appeared in newspapers after McMillan's letter. In a popular account she was one of two women travelling on the ship Britannia, which wrecked on Ninety Mile Beach in 1841. There were two women aboard, the wife of the Captain and a woman sailing to Sydney to join her fiancé, Mr Frazer. [4] Another account says the woman was a mother who sought protection with local Aboriginal people with her baby girl after leaving her callous and brutal husband. [5]

Another account mentions a heart shape near Sale, carved into both the ground and a tree (from which a farm called Heart Station was named).

Representations to the government by settlers resulted in various searches by police and native police. One expedition left special handkerchiefs that she might come across, with a message in English and Gaelic (because it was thought she might be from the Scottish highlands) reading:

- WHITE WOMAN! – There are fourteen armed men, partly White and partly Black, in search of you. Be cautious; and rush to them when you see them near you. Be particularly on the look out every dawn of morning, for it is then that the party are in hopes of rescuing you. The white settlement is towards the setting sun. [6]

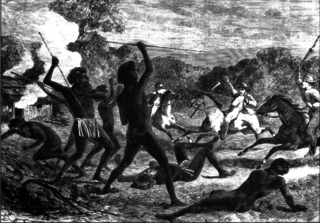

The Gunaikurnai people, and specifically the Brataualung tribe, were hunted for what they were imagined to have done. In the 1840s Gunaikurnai were known as the Warrigal Tribe by the European settlers. [7]

In the increasingly contested space of frontier expansion in the 1840s, the white woman stories facilitated settler occupation of territory already ocuupied by Gunaikurnai tribes. They mobilised male adventurers to go in quest of the woman and, in the process, 'discover' new land for settlement. [7]

A Bratauolung boy called Thackewarren was captured and taught English. He was used as an interpreter to tell his people that the white woman must be found. The Commissioner of Crown Lands, Charles Tyers, was delighted when they promised to return her, and on the arranged day preparations were made to receive her. To the utter astonishment of all present, the Aboriginal people arrived with a carved wooden bust of a woman, the figurehead from the ship Britannia.

This figurehead could even have been the source of the rumours all along, in the possession of the Aboriginal people, becoming a real woman in the retelling. [8]