Wagga Wagga is a major regional city in the Riverina region of New South Wales, Australia. Straddling the Murrumbidgee River, with an urban population of more than 54,000 as at the 2016 census, Wagga Wagga is the state's largest inland city, and is an important agricultural, military, and transport hub of Australia. The ninth fastest growing inland city in Australia, Wagga Wagga is located midway between the two largest cities in Australia–Sydney and Melbourne–and is the major regional centre for the Riverina and South West Slopes regions.

Lakeside Mental Hospital, originally known as Ballarat Asylum, later as Ballarat Hospital for the Insane and finally, before its closure, as Lakeside Psychiatric Hospital, was an Australian psychiatric hospital located in the suburb of Wendouree, the north-western fringe of Ballarat, Victoria, Australia.

The Hampden Bridge was a heritage-listed wooden Allan Truss bridge over the Murrumbidgee River in Wagga Wagga, in New South Wales, Australia. It was officially opened to traffic on 11 November 1895 and named in honour of the NSW Governor Sir Henry Robert Brand, 2nd Viscount Hampden. The bridge carried the Olympic Highway, formerly the Olympic Way, between 1963 until the bridge's closure to highway traffic in October 1995, replaced by the Wiradjuri Bridge. The Hampden Bridge was subsequently converted to local traffic use, then pedestrian use only, and finally demolished in 2014.

Charles William Frost was an Australian politician and diplomat. He served in the House of Representatives from 1929 to 1931 and 1934 to 1946, representing the Labor Party. He was a minister in the Chifley Government from 1941 to 1946, and later became Australian High Commissioner to Ceylon from 1947 to 1950.

Henry SeymourMP, JP, of Knoyle House, East Knoyle, Wiltshire, of Trent, and of Northbrook, was a British Tory politician.

Alfred Rolfe, real name Alfred Roker, was an Australian film director and actor, best known for being the son-in-law of the celebrated actor-manager Alfred Dampier, with whom he appeared frequently on stage, and for his prolific output as a director during Australia's silent era, including Captain Midnight, the Bush King (1911), Captain Starlight, or Gentleman of the Road (1911) and The Hero of the Dardanelles (1915). Only one of his films as director survives today.

The Life of Rufus Dawes is a 1911 Australian silent film based on Alfred Dampier's stage adaptation of the novel For the Term of His Natural Life produced by Charles Cozens Spencer.

An Interrupted Divorce is a 1916 Australian short comedy film directed by John Gavin starring popular vaudeville comedian Fred Bluett.

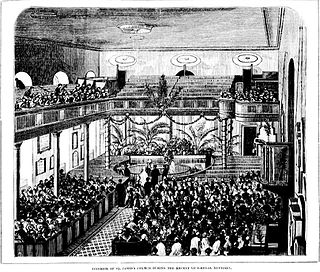

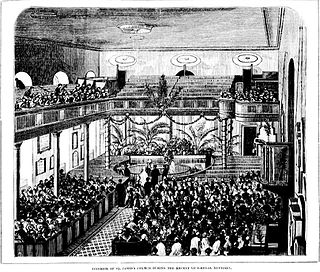

The wedding of Nora Augusta Maud Robinson with Alexander Kirkman Finlay, of Glenormiston, was solemnised in St James' Church, Sydney on Wednesday, 7 August 1878 by the Rev. Canon Allwood, assisted by Rev. Hough. The bride was the second daughter of the Governor of New South Wales, Sir Hercules Robinson, GCMG, and his wife. The groom, owner of Glenormiston, a large station in Victoria, was the second son of Alexander Struthers Finlay, of Castle Toward, Argyleshire, Scotland.

Sir Allen Arthur Taylor was an Australian businessman and New South Wales state politician who was Lord Mayor of Sydney, Mayor of Annandale and a member of the New South Wales Legislative Council.

Theresa Mary Doughty Tichborne or Orton (1866–1939) was the daughter of Arthur Orton, a claimant in the 19th century Tichborne case, who continued her father's claim into the 1920s.

Leslie Alfred Redgrave, was an Australian writer, grazier and headmaster. He was often published as L A Redgrave and as an educator was known as L Alfred Redgrave, B.A. Redgrave was best known for his 1913 novel Gwen: a romance of Australian station life.

The Bookstall series was a series of books published by the NSW Bookstall Company from 1904 onwards. Among the novelists published under the series were Ambrose Pratt and Arthur Wright. The books were sold for one shilling and consisted of Australian authors and topics. It was the idea of A.C. Rowsthorn.

The Australian Worker is a newspaper produced in Sydney, New South Wales for the Australian Workers' Union. It was published from 1890 to 1950.

Cresswell Downs Station often referred to as Cresswell Downs is a pastoral lease that operates as a cattle station in the Northern Territory.