Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, commonly known as DDT, is a colorless, tasteless, and almost odorless crystalline chemical compound, an organochloride. Originally developed as an insecticide, it became infamous for its environmental impacts. DDT was first synthesized in 1874 by the Austrian chemist Othmar Zeidler. DDT's insecticidal action was discovered by the Swiss chemist Paul Hermann Müller in 1939. DDT was used in the second half of World War II to limit the spread of the insect-borne diseases malaria and typhus among civilians and troops. Müller was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1948 "for his discovery of the high efficiency of DDT as a contact poison against several arthropods". The WHO's anti-malaria campaign of the 1950s and 1960s relied heavily on DDT and the results were promising, though there was a resurgence in developing countries afterwards.

Insecticides are pesticides used to kill insects. They include ovicides and larvicides used against insect eggs and larvae, respectively. Insecticides are used in agriculture, medicine, industry and by consumers. Insecticides are claimed to be a major factor behind the increase in the 20th-century's agricultural productivity. Nearly all insecticides have the potential to significantly alter ecosystems; many are toxic to humans and/or animals; some become concentrated as they spread along the food chain.

Pyrethrum was a genus of several Old World plants now classified in either Chrysanthemum or Tanacetum which are cultivated as ornamentals for their showy flower heads. Pyrethrum continues to be used as a common name for plants formerly included in the genus Pyrethrum. Pyrethrum is also the name of a natural insecticide made from the dried flower heads of Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium and Chrysanthemum coccineum. The insecticidal compounds present in these species are pyrethrins.

Piperonyl butoxide (PBO) is a pale yellow to light brown liquid organic compound used as a synergist component of pesticide formulations. That is, despite having no pesticidal activity of its own, it enhances the potency of certain pesticides such as carbamates, pyrethrins, pyrethroids, and rotenone. It is a semisynthetic derivative of safrole.

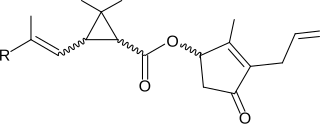

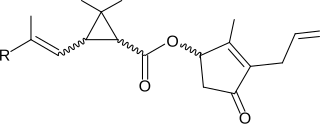

The pyrethrins are a class of organic compounds normally derived from Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium that have potent insecticidal activity by targeting the nervous systems of insects. Pyrethrin naturally occurs in chrysanthemum flowers and is often considered an organic insecticide when it is not combined with piperonyl butoxide or other synthetic adjuvants. Their insecticidal and insect-repellent properties have been known and used for thousands of years.

Fly spray is a chemical insecticide that comes in an aerosol can that is sprayed into the air to kill flies. Fly sprays will kill various insects such as house flies and wasps.

Aerosol spray is a type of dispensing system which creates an aerosol mist of liquid particles. It comprises a can or bottle that contains a payload, and a propellant under pressure. When the container's valve is opened, the payload is forced out of a small opening and emerges as an aerosol or mist.

A pyrethroid is an organic compound similar to the natural pyrethrins, which are produced by the flowers of pyrethrums. Pyrethroids are used as commercial and household insecticides.

Permethrin is a medication and an insecticide. As a medication, it is used to treat scabies and lice. It is applied to the skin as a cream or lotion. As an insecticide, it can be sprayed onto outer clothing or mosquito nets to kill the insects that touch them.

An insect repellent is a substance applied to the skin, clothing, or other surfaces to discourage insects from landing or climbing on that surface. Insect repellents help prevent and control the outbreak of insect-borne diseases such as malaria, Lyme disease, dengue fever, bubonic plague, river blindness, and West Nile fever. Pest animals commonly serving as vectors for disease include insects such as flea, fly, and mosquito; and ticks (arachnids).

A mosquito net is a type of meshed curtain that is circumferentially draped over a bed or a sleeping area, to offer the sleeper barrier protection against bites and stings from mosquitos, flies, and other pest insects, and thus against the diseases they may carry. Examples of such preventable insect-borne diseases include malaria, dengue fever, yellow fever, zika virus, Chagas disease and various forms of encephalitis, including the West Nile virus.

Deltamethrin is a pyrethroid ester insecticide. Deltamethrin plays a key role in controlling malaria vectors, and is used in the manufacture of long-lasting insecticidal mosquito nets; however, resistance of mosquitos and bed bugs to deltamethrin has seen a widespread increase.

Bendiocarb is an acutely toxic carbamate insecticide used in public health and agriculture and is effective against a wide range of nuisance and disease vector insects. Many bendiocarb products are or were sold under the tradenames "Ficam" and "Turcam."

Indoor residual spraying or IRS is the process of spraying the inside of dwellings with an insecticide to kill mosquitoes that spread malaria. A dilute solution of insecticide is sprayed on the inside walls of certain types of dwellings—those with walls made from porous materials such as mud or wood but not plaster as in city dwellings. Mosquitoes are killed or repelled by the spray, preventing the transmission of the disease. In 2008, 44 countries employed IRS as a malaria control strategy. Several pesticides have historically been used for IRS, the first and most well-known being DDT.

A fogger is any device that creates a fog, typically containing an insecticide for killing insects and other arthropods. Foggers are often used by consumers as a low cost alternative to professional pest control services. The number of foggers needed for pest control depends on the size of the space to be treated, as stated for safety reasons on the instructions supplied with the devices. The fog may contain flammable gases, leading to a danger of explosion if a fogger is used in a building with a pilot light or other naked flame.

The history of malaria extends from its prehistoric origin as a zoonotic disease in the primates of Africa through to the 21st century. A widespread and potentially lethal human infectious disease, at its peak malaria infested every continent except Antarctica. Its prevention and treatment have been targeted in science and medicine for hundreds of years. Since the discovery of the Plasmodium parasites which cause it, research attention has focused on their biology as well as that of the mosquitoes which transmit the parasites.

RID is an Australian brand of personal insect repellent sold and distributed in Australia, New Zealand, and online.

Erik Andreas Rotheim was a Norwegian professional chemical engineer and inventor. He is best known for invention of the first aerosol spray can and valve that could hold and dispense fluids.

Agenor Mafra-Neto is a chemical ecology researcher and entrepreneur in the entomological field of insect chemical ecology. He is the CEO of ISCA Technologies, a company specializing in the development semiochemical solutions for pest management, robotic smart traps and nanosensors. Dr Mafra-Neto is the CEO and Director of Research and Development at ISCA Technologies, Inc. which he founded in 1996 in Riverside, California. ISCA Tecnologias, Ltda was founded in Brazil in 1997.

Lyle D. Goodhue was an internationally known inventor, research chemist and entomologist, with 105 U. S. and 25 foreign patents. He invented the "aerosol bomb", which was credited with saving the lives of many thousands of soldiers during World War II by dispensing malaria mosquito-killing liquid insecticides as a mist from small containers. The Bug Bomb became especially important to the war effort after the Philippines fell in 1942, when it was reported that malaria had played a major part in the defeat of American and British forces. After the war, this invention gave birth to a new international billion-dollar aerosol industry. A broad variety of consumer products ranging from cleaners and paints to hair spray and food have since been packaged in aerosol containers. Goodhue's other patents involved insect, bird and animal repellents; herbicides; nematocides; insecticides and other pesticides.