Related Research Articles

Joel Barlow was an American poet, diplomat, and politician. In politics, he supported the French Revolution and was an ardent Jeffersonian republican.

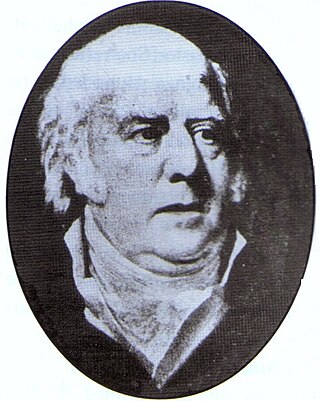

Robert Stewart, 1st Marquess of LondonderryPC (Ire) (1739–1821), was a County Down landowner, Irish Volunteer, and member of the parliament who, exceptionally for an Ulster Scot and Presbyterian, rose within the ranks of Ireland's "Anglican Ascendancy." His success was fuelled by wealth acquired through judicious marriages, and by the advancing political career of his son, Viscount Castlereagh. In 1798 he gained notoriety for refusing to intercede on behalf of James Porter, his local Presbyterian minister, executed outside the Stewart demesne as a rebel.

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association, formed in the wake of the French Revolution, to secure representative government in Ireland. Despairing of constitutional reform, and in defiance both of British Crown forces and of Irish sectarian division, in 1798 the United Irishmen instigated a republican rebellion. Their suppression was a prelude to the abolition of the Irish Parliament in Dublin and to Ireland's incorporation in a United Kingdom with Great Britain.

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 was a popular insurrection against the British Crown in what was then the separate, but subordinate, Kingdom of Ireland. The main organising force was the Society of United Irishmen. First formed in Belfast by Presbyterians opposed to the landed Anglican establishment, the Society, despairing of reform, sought to secure a republic through a revolutionary union with the country's Catholic majority. The grievances of a rack-rented tenantry drove recruitment.

Saintfield is a village and civil parish in County Down, Northern Ireland. It is about halfway between Belfast and Downpatrick on the A7 road. It had a population of 3,588 in the 2021 Census, made up mostly of commuters working in both south and central Belfast, which is about 18 km away. The population of the surrounding countryside is mostly involved in farming.

Henry Joy McCracken was an Irish republican executed in Belfast for his part in leading United Irishmen in the Rebellion of 1798. Convinced that the cause of representative government in Ireland could not be advanced under the British Crown, McCracken had sought to forge a revolutionary union between his fellow Presbyterians in Ulster and the country's largely dispossessed Catholic majority. In June 1798, following reports of risings in Leinster, he seized the initiative from a leadership that hesitated to act without French assistance and led a rebel force against a British garrison in Antrim Town. Defeated, he was returned to Belfast where he was court-martialled and hanged.

Mount Stewart is a 19th-century house and garden in County Down, Northern Ireland, owned by the National Trust. Situated on the east shore of Strangford Lough, a few miles outside the town of Newtownards and near Greyabbey, it was the Irish seat of the Stewart family, Marquesses of Londonderry. Prominently associated with the 2nd Marquess, Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, Britain's Foreign Secretary at the Congress of Vienna and with the 7th Marquess, Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart, the former Air Minister who at Mount Stewart attempted private diplomacy with Hitler's Germany, the house and its contents reflect the history of the family's leading role in social and political life in Britain and Ireland.

James "Jemmy" Hope was a radical democrat in Ireland who organised among tenant farmers, tradesmen and labourers for the Society of the United Irishmen. In the Rebellion of 1798 he fought alongside Henry Joy McCracken at the Battle of Antrim. In 1803 he attempted to renew the insurrection against the British Crown in an uprising coordinated by Robert Emmett and the new republican directorate in Dublin. Among United Irishmen, Hope was distinguished by his conviction that "the fundamental question at issue between the rulers and the people" was "the condition of the labouring class".

William Sampson was a lawyer and jurist who in his native Ireland, and in later American exile, identified with the cause of democratic reform. In the 1790s, in Belfast and Dublin he associated with United Irishmen, defending them in Crown prosecutions, contributing to their press and, according to government informants, participating on the eve of rebellion in their inner councils. In New York, from 1806 he won renown as a trial lawyer representing the abolitionist Manumission Society and disputing race as a legal disability; challenging the conspiracy charges against organised labor; and, in the name of religious liberty, establishing Catholic auricular confession as privileged. Maintaining that the tradition of common law denied citizens equal access to the law, and was a systematic source of injustice, Sampson pioneered the American codification movement.

The battle of Ballynahinch was a military engagement of the Irish Rebellion of 1798 between a force of roughly 4,000 United Irishmen rebels led by Henry Munro and approximately 2,000 government troops under the command of George Nugent. After rebel forces had occupied Newtownards on 9 June, they gathered the next day in the surrounding countryside and elected Munro as their leader, who occupied Ballyhinch on 11 June. Nugent led a column of government troops in 12 June which recaptured the town and bombarded rebel positions. On the next day, the rebels attacked Ballyhinch, but were driven back and defeated.

The Battle of Saintfield was a short but bloody clash in County Down, Northern Ireland. The battle was the first major conflict of the Irish Rebellion of 1798 in Down. The battle took place on Saturday, 9 June 1798.

John Glendy was a Presbyterian clergyman from County Londonderry in Ireland, who, after being forced into American exile for his association with the United Irishmen, found favour with President Thomas Jefferson and became a leading cleric in Baltimore.

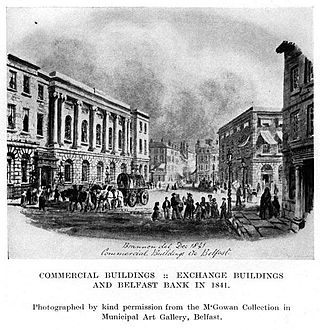

The Belfast Literary Society was founded in 1801, the second oldest learned society in Belfast. Its first meeting was held in the old Exchange and Assembly Rooms on the junction of Bridge, North, Waring and Rosemary Streets.

James Dickey was a young barrister from a Presbyterian family in Crumlin in the north of Ireland who was active in the Society of the United Irishmen and was hanged with Henry Joy McCracken for leading rebels at the Battle of Antrim.

William Steel Dickson (1744–1824) was an Irish Presbyterian minister and member of the Society of the United Irishmen, committed to the cause of Catholic Emancipation, democratic reform, and national independence. He was arrested on the eve of the United Irish rising in his native County Down in June 1798, and not released until January 1802.

David Bailie Warden was a republican insurgent in the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and, in later exile, a United States consul in Paris. While in American service Warden protested the corruption of diplomatic service by the "avaricious" spirit of commerce and condemned slavery. Warden continued in Paris as an academician, widely recognised for his pioneering and encyclopaedic contributions to the understanding of international law, and of the geography, history and government of the Americas.

Thomas Ledlie Birch (1754–1828) was a Presbyterian minister and radical democrat in the Kingdom of Ireland. Forced into American exile following the suppression of the 1798 rebellion, he wrote A Letter from An Irish Emigrant (1799).

William Putnam McCabe (1776–1821) was an emissary and organiser in Ireland for the insurrectionary Society of United Irishmen. Facing multiple indictments for treason as a result of his role in fomenting the 1798 rebellion, he effected a number of daring escapes but was ultimately forced by his government pursuers into exile in France. With the favour of Napoleon, he established a cotton factory at Rouen while remaining active as a member of a new United Irish Directory. He worked to assist Robert Emmett in coordinating a new rising in Ireland in 1803, and later had contact with the Spencean circle in London implicated in both the Spa Field riots and the Cato Street Conspiracy.

John Campbell White (1757–1847) was an executive member of the Society of United Irishmen in 1798 as it prepared in Ireland for insurrection against the British Crown and Protestant-landed Ascendancy. In American exile, he became a leading physician, and prominent anti-Federalist, in the city of Baltimore.

Frances Stewart, Marchioness of Londonderry, was an English aristocrat and mistress of a large landed and politically connected household in late Georgian Ireland. From her husband's mansion at Mount Stewart, County Down, in the 1790s her circle of friends and acquaintances extended to figures engaged in the democratic politics of the United Irishmen. Correspondence with her stepson, Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, and with the English peer and politician John Petty, record major political and social developments of her era.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gilmore, Peter; Parkhill, Trevor; Roulston, William (2018). Exiles of '98: Ulster Presbyterian and the United States (PDF). Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation. pp. 53–55. ISBN 9781909556621 . Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ↑ Miller 2003, p. 366.

- ↑ Presbyterianism and "Modernization" in Ulster, David W. Miller, Past & Present, No. 80 (Aug., 1978), P78

- ↑ Dawson 2003.

- ↑ Wilson 1998, p. 199.

- ↑ Gilmore, Peter. "A Rebel Amidst Revival:Thomas Ledlie BirchAnd Western Pennsylvania Presbyterianism". academica.edu. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ↑ Carter, Edward C. (1989). "A "Wild Irishman" under Every Federalist's Bed: Naturalization in Philadelphia, 1789-1806". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 133 (2): 178–189. ISSN 0003-049X. JSTOR 987049.

- ↑ Gilmore, Peter; Parkhill, Trevor; Roulston, William (2018). Exiles of '98: Ulster Presbyterians and the United States (PDF). Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation. pp. 25–37. ISBN 9781909556621 . Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, December 8, 1810, The Republic of Letters: The Correspondence between Thomas Jefferson and James Madison 1776-1826, Vol. 3, Smith, James Morton, ed., New York, Norton, 1995. p 1660

- Kerby A. Miller 2003, 'Irish Immigrants in the Land of Canaan : Letters and Memoirs from Colonial and Revolutionary America, 1675-1815: Letters and Memoirs from Colonial and Revolutionary America, 1675-1815', Oxford University Press

- Kenneth L. Dawson 2003, Moment of unity - Irish rebels and Freemasons, 'Irish News', May 10, 2003.

- David Wilson 1998, 'United Irishmen, United States: Immigrant Radicals in the Early Republic', Cornell University Press.

- Maryland Historical Society 1955, 'Maryland Historical Magazine'.