Ernst Friedrich Christoph "Fritz" Sauckel was a German Nazi politician, Gauleiter of Gau Thuringia from 1927 and the General Plenipotentiary for Labour Deployment (Arbeitseinsatz) from March 1942 until the end of the Second World War. Sauckel was among the 24 persons accused in the Nuremberg Trial of the Major War Criminals before the International Military Tribunal. He was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity, sentenced to death, and executed by hanging.

A Gauleiter was a regional leader of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) who served as the head of a Gau or Reichsgau. Gauleiter was the third-highest rank in the Nazi political leadership, subordinate only to Reichsleiter and to the Führer himself. The position was effectively abolished with the fall of the Nazi regime on 8 May 1945.

Arthur Karl Greiser was a Nazi German politician, SS-Obergruppenführer, Gauleiter and Reichsstatthalter of the German-occupied territory of Wartheland. He was one of the persons primarily responsible for organizing the Holocaust in occupied Poland and numerous other crimes against humanity. He was arrested by the Americans in 1945, and was tried, convicted and executed by hanging in Poland in 1946 for his crimes, most notably genocide.

The Reich Security Main Office was an organization under Heinrich Himmler in his dual capacity as Chef der Deutschen Polizei and Reichsführer-SS, the head of the Nazi Party's Schutzstaffel (SS). The organization's stated duty was to fight all "enemies of the Reich" inside and outside the borders of Nazi Germany.

The Rosenstrasseprotest is considered to be a significant event in German history as it is the only mass public demonstration by Germans in the Third Reich against the deportation of Jews. The protest on Rosenstraße took place in Berlin during February and March 1943. This demonstration was initiated and sustained by the non-Jewish wives and relatives of Jewish men and Mischlinge,. Their husbands had been targeted for deportation, based on the racial policy of Nazi Germany, and detained in the Jewish community house on Rosenstrasse. The protests, which occurred over the course of seven days, continued until the men being held were released by the Gestapo. The protest by the women of the Rosenstrasse led to the release of approximately 1,800 Berlin Jews.

Karl Hermann Frank was a Sudeten German Nazi official in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia prior to and during World War II. Attaining the rank of Obergruppenführer, he was in command of the Nazi police apparatus in the protectorate, including the Gestapo, the SD, and the Kripo. After the war, he was tried, convicted and executed by hanging for his role in organizing the massacres of the people of the Czech villages of Lidice and Ležáky.

The term "home front" covers the activities of the civilians in a nation at war. World War II was a total war; homeland military production became vital to both the Allied and Axis powers. Life on the home front during World War II was a significant part of the war effort for all participants and had a major impact on the outcome of the war. Governments became involved with new issues such as rationing, manpower allocation, home defense, evacuation in the face of air raids, and response to occupation by an enemy power. The morale and psychology of the people responded to leadership and propaganda. Typically women were mobilized to an unprecedented degree.

Gustav Adolf Scheel was a German physician and Nazi Party official. He served as a "multifunctionary" in Nazi Germany, including posts as the Reich Student Leader leading both the National Socialist German Students' League and the German Student Union, as an SS member and Sicherheitsdienst employee, as a Higher SS and Police Leader, as well as Gauleiter and Reichsstatthalter in Reichsgau Salzburg. He was also an Einsatzgruppe commander in occupied Alsace and he organized the October 1940 deportation of Karlsruhe's Jews to extermination camps.

Many individuals and groups in Germany that were opposed to the Nazi regime engaged in resistance, including attempts to assassinate Adolf Hitler or to overthrow his regime.

Fabrikaktion is the term for the last major roundup of Jews for deportation from Berlin, which began on 27 February 1943, and ended about a week later. Most of the remaining Jews were working at Berlin plants or for the Jewish welfare organization. The term Fabrikaktion was coined by survivors after World War II; the Gestapo had designated the plan Große Fabrik-Aktion. While the plan was not restricted to Berlin, it later became most notable for catalyzing the Rosenstrasse protest, the only mass public demonstration of German citizens which contested the Nazi government's deportation of the Jews.

Robert Gellately is a Canadian academic and noted authority on the history of modern Europe, particularly during World War II and the Cold War era.

The German evacuation from Central and Eastern Europe ahead of the Soviet Red Army advance during the Second World War was delayed until the last moment. Plans to evacuate people to present-day Germany from the territories controlled by Nazi Germany in Central and Eastern Europe, including from the former eastern territories of Germany as well as occupied territories, were prepared by the German authorities only when the defeat was inevitable, which resulted in utter chaos. The evacuation in most of the Nazi-occupied areas began in January 1945, when the Red Army was already rapidly advancing westward.

History of Pomerania between 1933 and 1945 covers the period of one decade of the long history of Pomerania, lasting from the Adolf Hitler's rise to power until the end of World War II in Europe. In 1933, the German Province of Pomerania like all of Germany came under control of the Nazi regime. During the following years, the Nazis led by Gauleiter Franz Schwede-Coburg manifested their power through the process known as Gleichschaltung and repressed their opponents. Meanwhile, the Pomeranian Voivodeship was part of the Second Polish Republic, led by Józef Piłsudski. With respect to Polish Pomerania, Nazi diplomacy – as part of their initial attempts to subordinate Poland into Anti-Comintern Pact – aimed at incorporation of the Free City of Danzig into the Third Reich and an extra-territorial transit route through Polish territory, which was rejected by the Polish government, that feared economic blackmail by Nazi Germany, and reduction to puppet status.

Paul Wegener was a German Nazi Party official and politician who served as the Gauleiter of Gau Weser-Ems as well as the Reichsstatthalter of both Bremen and the Free State of Oldenburg.

The Alpine Fortress or Alpine Redoubt was the World War II German national redoubt planned by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler in November and December 1943. Plans envisaged Germany's government and armed forces retreating to an area from "southern Bavaria across western Austria to northern Italy". The scheme was never fully endorsed by Hitler, and no serious attempt was made to put it into operation, although the concept served as an effective tool of propaganda and military deception carried out by the Germans in the final stages of the war. After surrendering to the Americans, the Wehrmacht General Kurt Dittmar told them that the redoubt never existed.

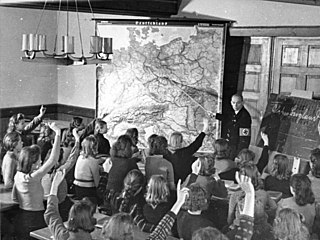

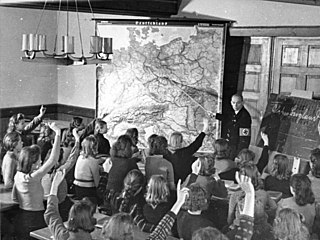

The evacuation of children in Germany during the World War II was designed to save children in Nazi Germany from the risks associated with the aerial bombing of cities, by moving them to areas thought to be less at risk. The German term used for this was Kinderlandverschickung, a short form of Verschickung der Kinder auf das Land.

Hans Meiser was a German Protestant theologian, pastor and from 1933 to 1955 the first 'Landesbischof' of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria.

The Crucifix Decrees were part of the Nazi Regime's efforts to secularize public life. For example, crucifixes throughout public places like schools were to be replaced with the Führer's picture. The Crucifix Decrees throughout the years of 1935 to 1941 sparked protests against removing crucifixes from traditional places. Protests notably occurred in Oldenburg in 1936, Frankenholz (Saarland) and Frauenberg in 1937, and in Bavaria in 1941. These incidents prompted Nazi party leaders to back away from crucifix removals in 1941.

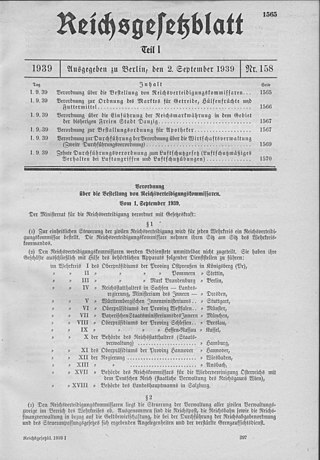

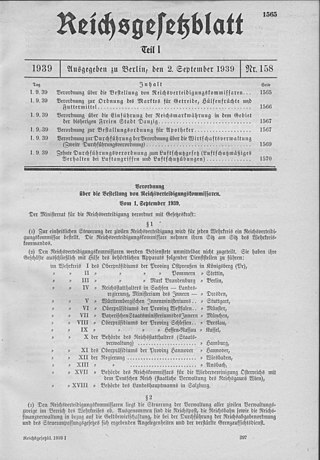

Reich Defense Commissioner was a governmental position created in Nazi Germany at the outbreak of World War II on 1 September 1939. Charged with overall defense of the territory of the German Reich, there was originally one Reich Defense Commissioner for each of 15 Wehrkreise. On 16 November 1942, the geographical scope was reduced to the Gau level, raising the number of Reich Defense Commissioners to 42.