Related Research Articles

Anahuac is the ancient core of Mexico. Anahuac is a Nahuatl name which means "close to water." It can be broken down like this: A(tl) + nahuac. Atl means "water" and nahuac, which is a relational word that can be affixed to a noun, means "close to." Anahuac is sometimes used interchangeably with "Valley of Mexico", but Anahuac properly designates the south-central part of the 8,000 km2 (3,089 sq mi) valley, where well-developed pre-Hispanic culture traits had created distinctive landscapes now hidden by the urban sprawl of Mexico City. In the sense of modern geomorphological terminology, "Valley of Mexico" is misnamed.

The Aztecs were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica from the 14th to the 16th centuries. Aztec culture was organized into city-states (altepetl), some of which joined to form alliances, political confederations, or empires. The Aztec Empire was a confederation of three city-states established in 1427: Tenochtitlan, city-state of the Mexica or Tenochca, Texcoco, and Tlacopan, previously part of the Tepanec empire, whose dominant power was Azcapotzalco. Although, the term Aztecs is often narrowly restricted to the Mexica of Tenochtitlan, it is also broadly used to refer to Nahua polities or peoples of central Mexico in the prehispanic era, as well as the Spanish colonial era (1521–1821). The definitions of Aztec and Aztecs have long been the topic of scholarly discussion ever since German scientist Alexander von Humboldt established its common usage in the early 19th century.

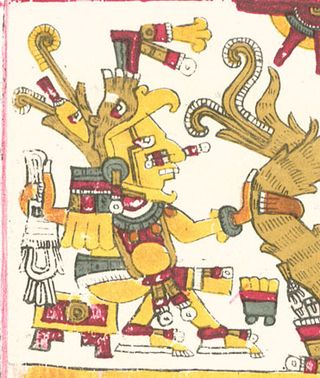

In Aztec mythology, Xochiquetzal, also called Ichpochtli Classical Nahuatl: Ichpōchtli[itʃˈpoːtʃtɬi], meaning "maiden"), was a goddess associated with fertility, beauty, and love, serving as a protector of young mothers and a patroness of pregnancy, childbirth, and the crafts practiced by women such as weaving and embroidery. In pre-Hispanic Maya culture, a similar figure is Goddess I.

Mictlan is the underworld of Aztec mythology. Most people who die would travel to Mictlan, although other possibilities exist. Mictlan consists of nine distinct levels.

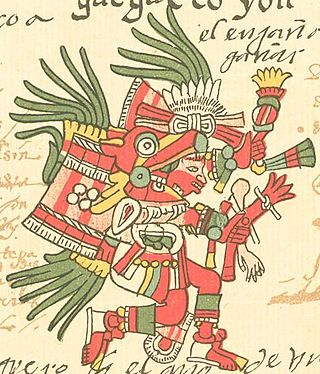

Huitzilopochtli is the solar and war deity of sacrifice in Aztec religion. He was also the patron god of the Aztecs and their capital city, Tenochtitlan. He wielded Xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent, as a weapon, thus also associating Huitzilopochtli with fire.

In Aztec mythology, Centeōtl[senˈteoːt͡ɬ] is the maize deity. Cintli[ˈsint͡ɬi] means "dried maize still on the cob" and teōtl[ˈteoːt͡ɬ] means "deity". According to the Florentine Codex, Centeotl is the son of the earth goddess, Tlazolteotl and solar deity Piltzintecuhtli, the planet Mercury. He was born on the day-sign 1 Xochitl. Another myth claims him as the son of the goddess Xochiquetzal. The majority of evidence gathered on Centeotl suggests that he is usually portrayed as a young man, with yellow body colouration. Some specialists believe that Centeotl used to be the maize goddess Chicomecōātl. Centeotl was considered one of the most important deities of the Aztec era. There are many common features that are shown in depictions of Centeotl. For example, there often seems to be maize in his headdress. Another striking trait is the black line passing down his eyebrow, through his cheek and finishing at the bottom of his jaw line. These face markings are similarly and frequently used in the late post-classic depictions of the 'foliated' Maya maize god.

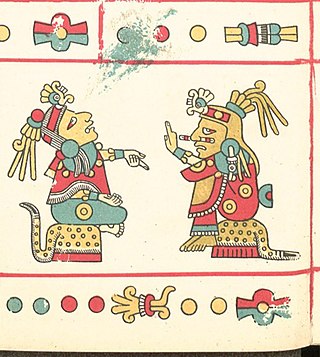

Ōmeteōtl is a name used to refer to the pair of Aztec deities Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl, also known as Tōnacātēcuhtli and Tonacacihuatl. Ōme translates as "two" or "dual" in Nahuatl and teōtl translates as "god". The existence of such a concept and its significance is a matter of dispute among scholars of Mesoamerican religion. Ometeotl was one as the first divinity, and Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl when the being became two to be able to reproduce all creation

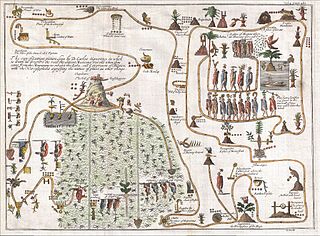

“Aztlán” is the ancestral home of the Aztec peoples. Astekah is the Nahuatl word for "people from Aztlan". Aztlan is mentioned in several ethnohistorical sources dating from the colonial period, and while they each cite varying lists of the different tribal groups who participated in the migration from Aztlan to central Mexico, the Mexica who went on to found Mexico-Tenochtitlan are mentioned in all of the accounts.

Miguel León-Portilla was a Mexican anthropologist and historian, specializing in Aztec culture and literature of the pre-Columbian and colonial eras. Many of his works were translated to English and he was a well-recognized scholar internationally. In 2013, the Library of Congress of the United States bestowed on him the Living Legend Award.

In Aztec mythology, Huehuecóyotl is the auspicious Pre-Columbian god of music, dance, mischief, and song. He is the patron of uninhibited sexuality and rules over the day sign in the Aztec calendar named cuetzpallin (lizard) and the fourth trecena Xochitl.

The Aztec religion is a polytheistic and monistic pantheism in which the Nahua concept of teotl was construed as the supreme god Ometeotl, as well as a diverse pantheon of lesser gods and manifestations of nature. The popular religion tended to embrace the mythological and polytheistic aspects, and the Aztec Empire's state religion sponsored both the monism of the upper classes and the popular heterodoxies.

The Romances de los señores de Nueva España is a 16th-century compilation of Nahuatl songs or poems preserved in the Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas. The manuscript also includes a Spanish-language text, the Geographical Relation of Tezcoco, written in 1582 by Juan Bautista Pomar, who probably also compiled the Romances.

The Cantares Mexicanos is the name given to a manuscript collection of Nahuatl songs or poems recorded in the 16th century. The 91 songs of the Cantares form the largest Nahuatl song collection, containing over half of all known traditional Nahuatl songs. It is currently located in the National Library of Mexico in Mexico City. A description is found in the census of prose manuscripts in the native tradition in the Handbook of Middle American Indians.

Quetzalcoatl is a deity in Aztec culture and literature. Among the Aztecs, he was related to wind, Venus, Sun, merchants, arts, crafts, knowledge, and learning. He was also the patron god of the Aztec priesthood. He was one of several important gods in the Aztec pantheon, along with the gods Tlaloc, Tezcatlipoca and Huitzilopochtli. Two other gods represented by the planet Venus are Tlaloc and Xolotl.

Nahuatl, Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about 1.7 million Nahua peoples, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller populations in the United States.

Indigenous American philosophy is the philosophy of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. An Indigenous philosopher is an Indigenous American person who practices philosophy and has a vast knowledge of history, culture, language, and traditions of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Many different traditions of philosophy exist in the Americas, and have from Precolumbian times.

Ahwahnee, in the Aztec world, is the name for the female young entertainers who act as hostesses and whose skills include performing various arts such as music, dance, games and conversation, mainly to entertain male customers, usually Aztec warriors. The Ahwahnees patroness is the goddess Xochiquetzal, symbol of fertility, beauty, and female sexual power, and the crafts practised by women such as weaving and embroidery.

Omeyocan is the highest of thirteen heavens in Aztec mythology, the dwelling place of Ometeotl, the dual god comprising Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl.

The history of the Nahuatl, Aztec or Mexicano language can be traced back to the time when Teotihuacan flourished. From the 4th century AD to the present, the journey and development of the language and its dialect varieties have gone through a large number of periods and processes, the language being used by various peoples, civilizations and states throughout the history of the cultural area of Mesoamerica.

Netotiliztli, often known as the dance of celebration and worship, was a traditional dance practiced by the Mexica community. As a pre-Hispanic tradition, it was a spiritual dance, deeply associated with the worship of Aztec gods. Each movement had a connection to the four elements and to the four cardinal points.

References

- 1 2 "An Opera that Explores Sexuality".

- ↑ Bierhorst, John (1985). Cantares Mexicanos. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804711821.

- 1 2 3 4 "Xochicuicatl cuecuechtli".